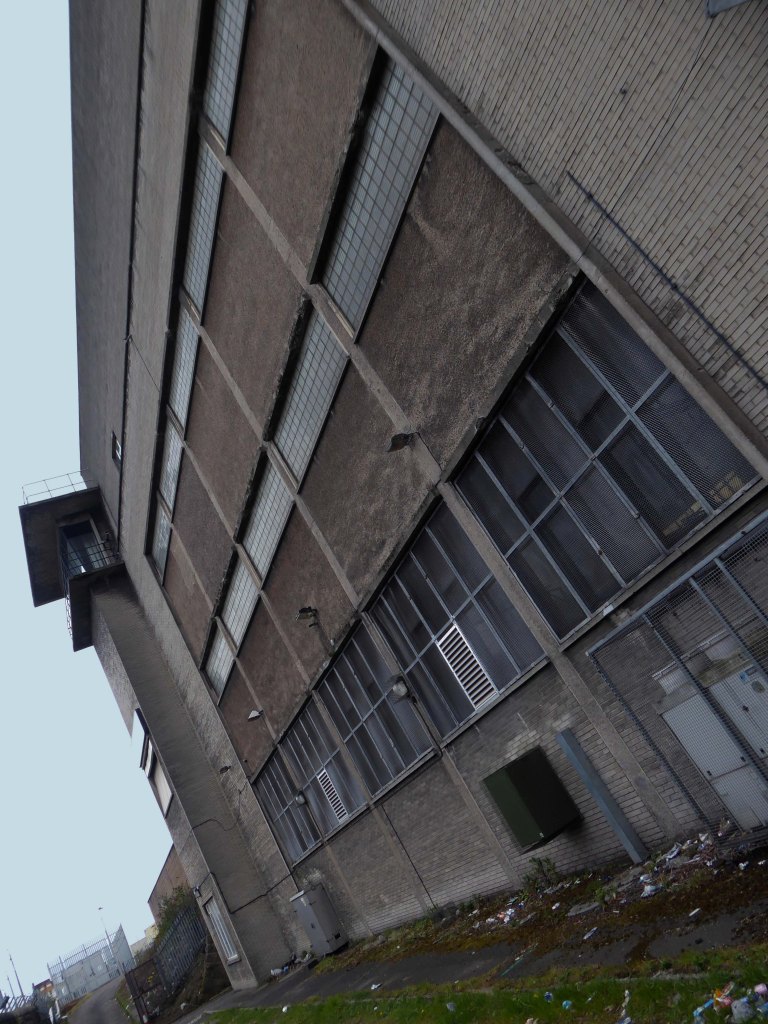

The Gallery is housed in a modern, custom-built facility that is part of the extensive Glasgow University Library complex, designed by William Whitfield.

Sir William Whitfield had roots in concrete and brick brutalism but took contextual postmodernism to a Palladian mansion that traditionalists admired. Principal of a small office for almost 50 years, his diversity of work was shot through with recurring themes and was distinguished by thoughtful synthesis of precedent.

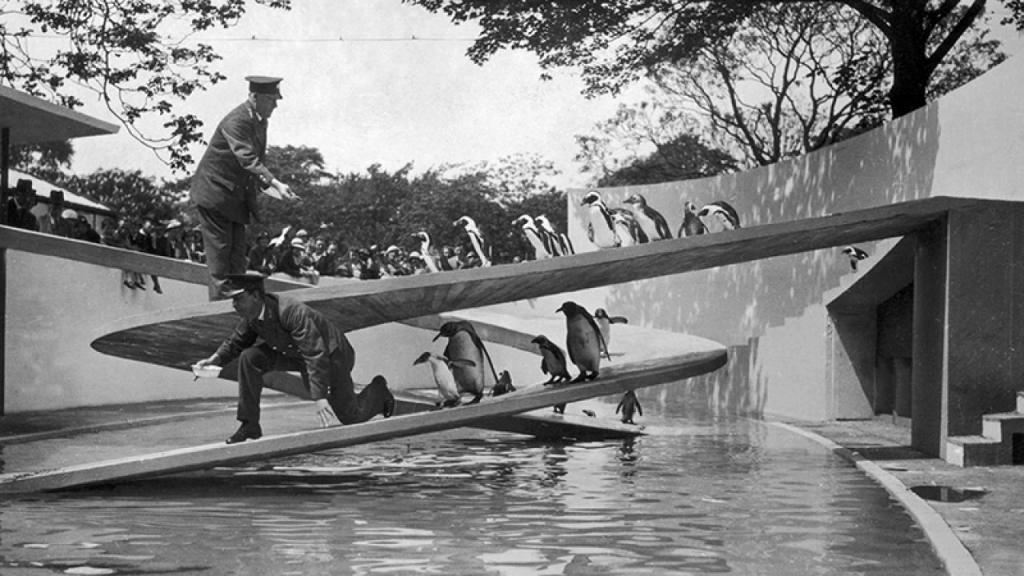

This displays the university’s extensive art collection, and features an outdoor sculpture garden.

The bas relief aluminium doors to the Hunterian Gallery were designed by sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi.

The gallery’s collection includes a large number of the works of James McNeill Whistler and the majority of the watercolours of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

The Mackintosh House is a modern concrete building, part of the gallery-library complex.

The Mackintosh House comprises the principal interiors of the original house – including the dining room, studio-drawing room and bedroom, largely replicating the room layout of the old end-of-terrace building. It features the meticulously reassembled interiors from the Mackintoshes’ home, including items of original furniture, fitments and decorations.