The first school of design in the UK, the Government School of Design, was established in 1837 and went on to become the Royal College of Art. It marked the beginnings of the development of technical education in the UK, which expanded in the remaining decades of the 19th century, and was largely instigated by the Science and Art Department of the Board of Trade, formed in 1853. In 1856 the Science and Art Department transferred from the Board of Trade to the Education Department and administered grant-aid to art schools from 1856 and to schools of design and technical schools from 1868.

The Technical Instruction Act 1889 permitted local authorities to levy rates to aid technical or manual instruction. County and borough councils began to provide technical instruction by day and evening classes.

The Local Taxation Customs and Excise Act 1890 diverted ‘whisky money’ from publicans to local authorities for assisting technical education or relieving rates, boosting investment in technical instruction.

By the end of the 19th century continuing education was provided by a variety of bodies in a number of forms:

- day continuation schools

- evening schools and classes

- mechanics institutes

- schools of art

- polytechnics

- university extension lectures

- tutorial classes

- working men’s colleges and courses

Under the 1902 Education Act, changes to conditions attached to government grants encouraged the expansion of technical education. Local Education Authorities took over most of the evening continuation schools.

Major changes occurred after the Second World War. Junior technical schools , commercial schools and schools of art were fully integrated into the revised system of secondary education.

The development of technical and art education were inextricably linked to the industrialisation of the north of England.

The Textile Court or main gallery space of the Arts and Crafts Museum of the Manchester Municipal School of Art, photographed in 1898-1901.

Manchester School of Art was established in 1838 as the Manchester School of Design. It is the second oldest art school in the United Kingdom after the Royal College of Art which was founded the year before.

The school opened in the basement of the Manchester Royal Institution on Mosley Street in 1838. It became the School of Art in 1853 and moved to Cavendish Street in 1880. It was subsequently named the Municipal School of Art. In 1880, the school admitted female students, at the time the only higher education available to women, although men and women were segregated. The school was extended in 1897.

The mill towns which encircled the city of Manchester each had their own independent colleges of Art and Design.

Textiles in particular required practitioners in surface pattern and garment design and construction, innovative and skilled students were in demand for print, engineering, architecture and general manufacturing – who also required the services of typographers, illustrators, commercial and graphic designers.

Having left school aged sixteen in 1971, all I ever wanted to do was go to Art School.

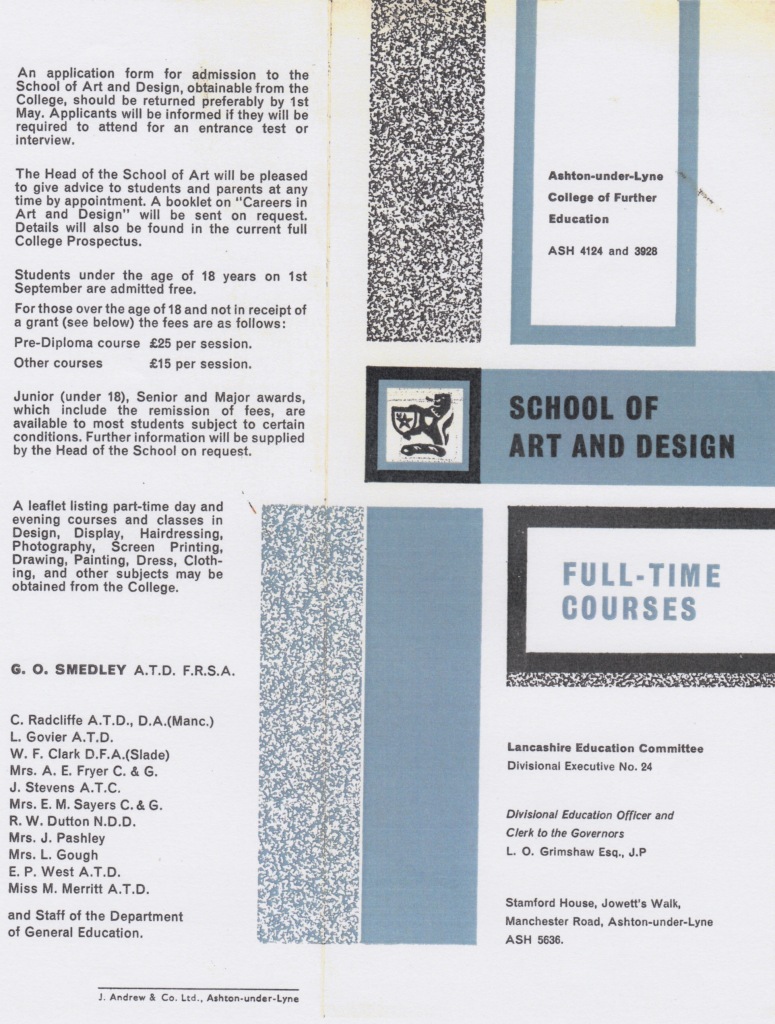

My local college was the then Ashton under Lyne College of Further Education – the full-time mode of study was then a two year Pre-Diploma Course.

It had begun life as the Heginbottom School of Art based at – Heginbottom Technical Schools School of Art and Free Library Old Street Ashton-under-Lyne.

The new Technical Schools and Free Library, which has just been completed were opened for students without any formal ceremony. The building has been erected from designs prepared by Messrs John Eaton and Sons, architects, Ashton, at a cost, including fittings of £16,000.

The building is now Grade II listed and the library and college long gone.

A blue plaque in the main entrance celebrates the former student Raymond Ray-Jones.

Father of photographer Tony Ray-Jones.

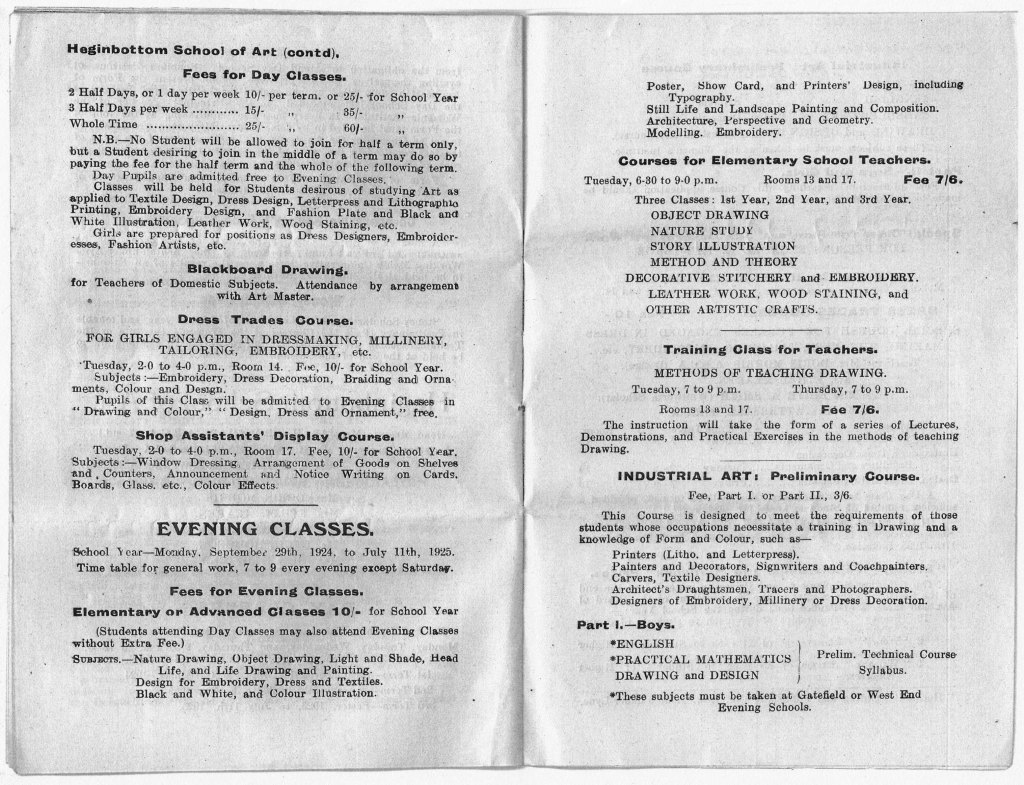

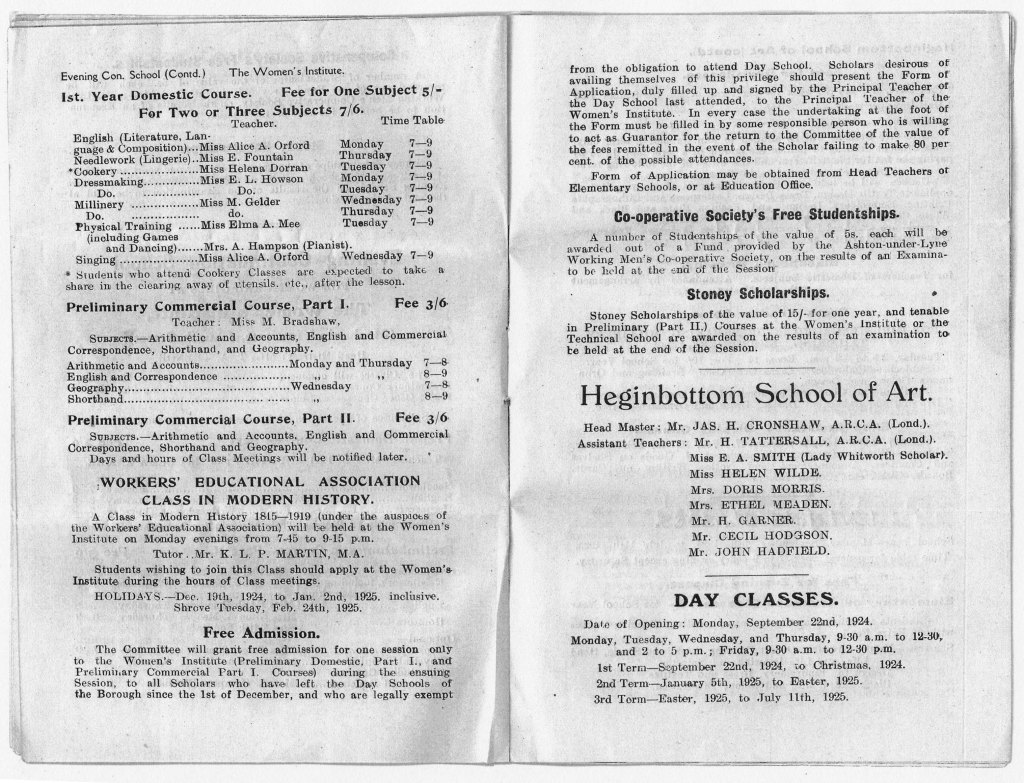

This is the syllabus of 1924-25 – courses take place in evening as students would have been working during the day.

Many of the classes were clearly defined by gender.

Drawing was a seen as a skill which underpinned he majority of disciplines.

Some of the provision was non-vocational.

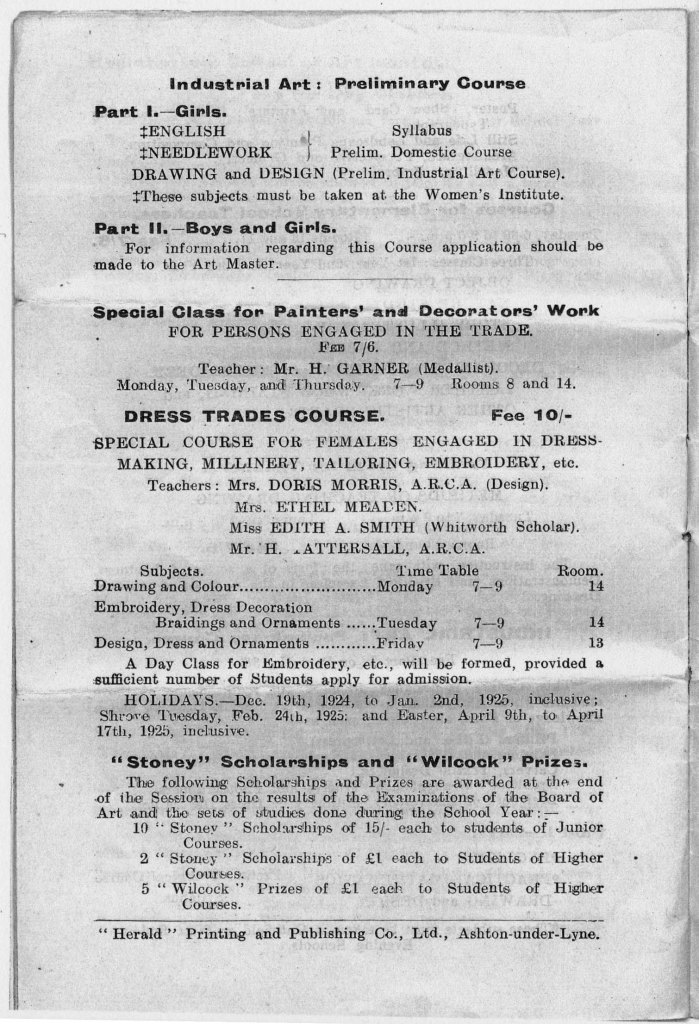

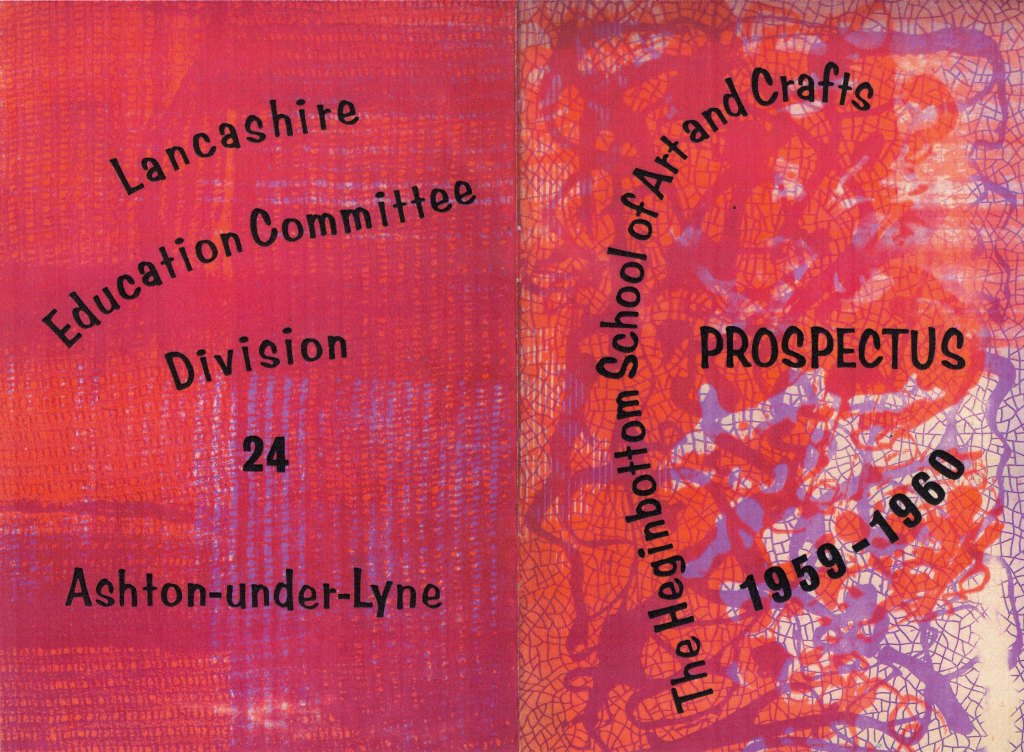

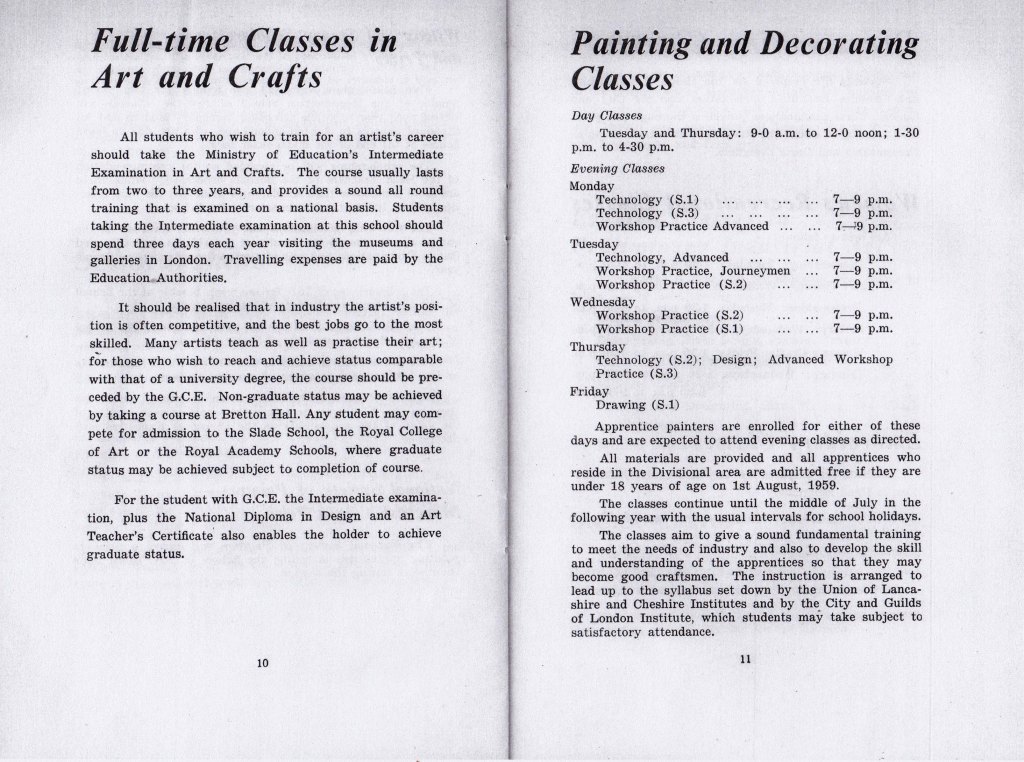

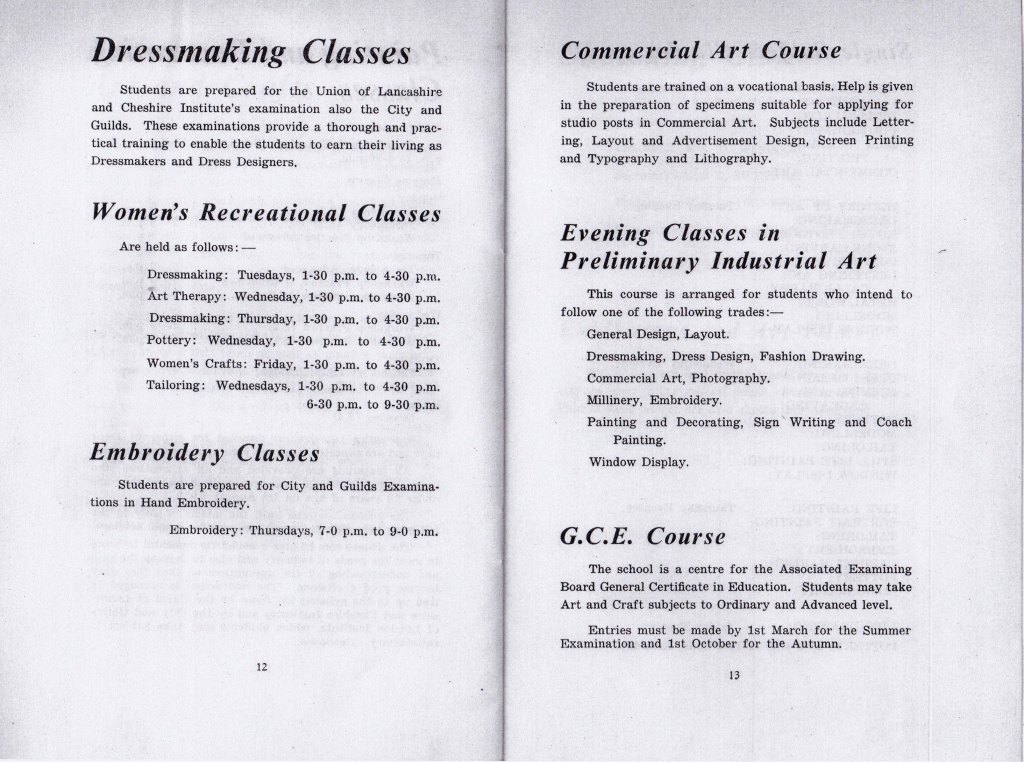

Forward now to 1959-60.

There are now full-time courses in Art and Design – though there were no degree courses until 1974, students would find employment, places on a teacher training course or possibly progress to one of the London colleges, which did have graduate status.

There were still clear distinctions in what were considered women’s skills, which also reflected the patterns of employment.

There was also an increasing distinction between specialisms, Fine and Applied Arts taking diverging paths.

An astounding range of skills were available on a part time evening basis, opening up vocational or non-vocational options.

These were always affordable and well attended.

Art and design education had undergone a major transformation in the early 1960s. The Coldstream report -1960/ 1962 had restructured art education: the existing National Diploma in Design had been replaced with a three year Diploma in Art and Design in 1963. The Dip.AD was conceived as providing ‘a liberal education in art’ and had four areas of specialisation: textiles/fashion, three dimensional design, graphic design, and fine art. Other subjects, such as electronic media, photography and film, were incorporated into fine art or graphic design courses.

The Dip.AD was intended to be the equivalent of a university degree. To achieve this academic entry requirements, at least five O’ levels, were introduced; although exceptions could be granted for “students with outstanding artistic promise”, very few were: only 36 were made in 1967 . The Dip. AD itself contained a compulsory academic element and enhanced art history component: taken together these accounted for 15 per cent of course time and 20 per cent of the final pass mark. One year Pre-diploma (latterly Foundation) courses termed Basic Design, were also introduced, these a product of the Bauhaus approach to art education, pioneered in the UK by and Richard Hamilton, Tom Hudson, Harr Thubron, Maurice de Sausmarez, and Victor Pasmore. Basic Design was a form of creative education involving basic analytic experiment and a clearing of the slate.

Centre for Global Higher Education

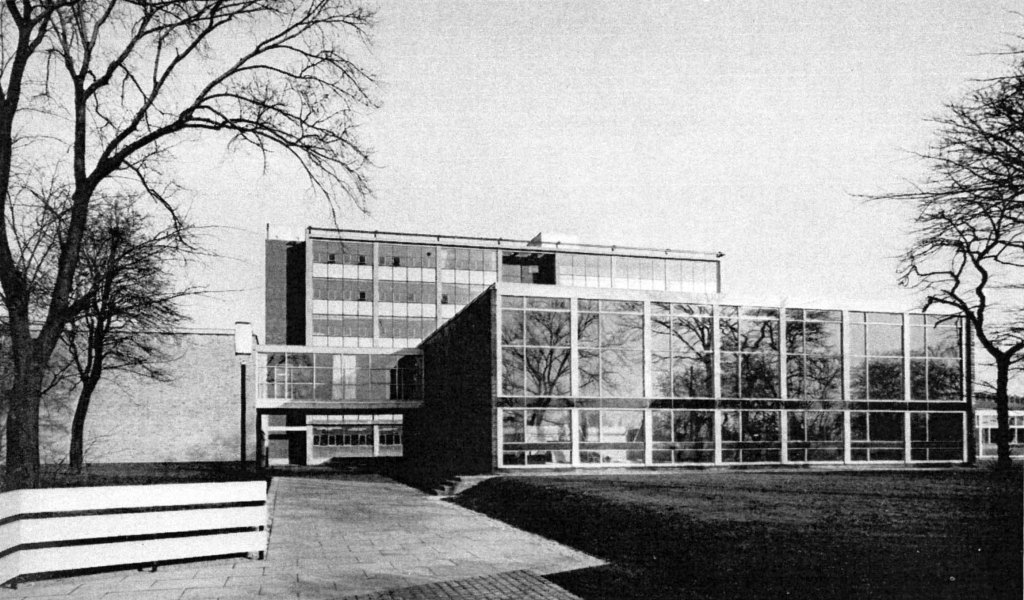

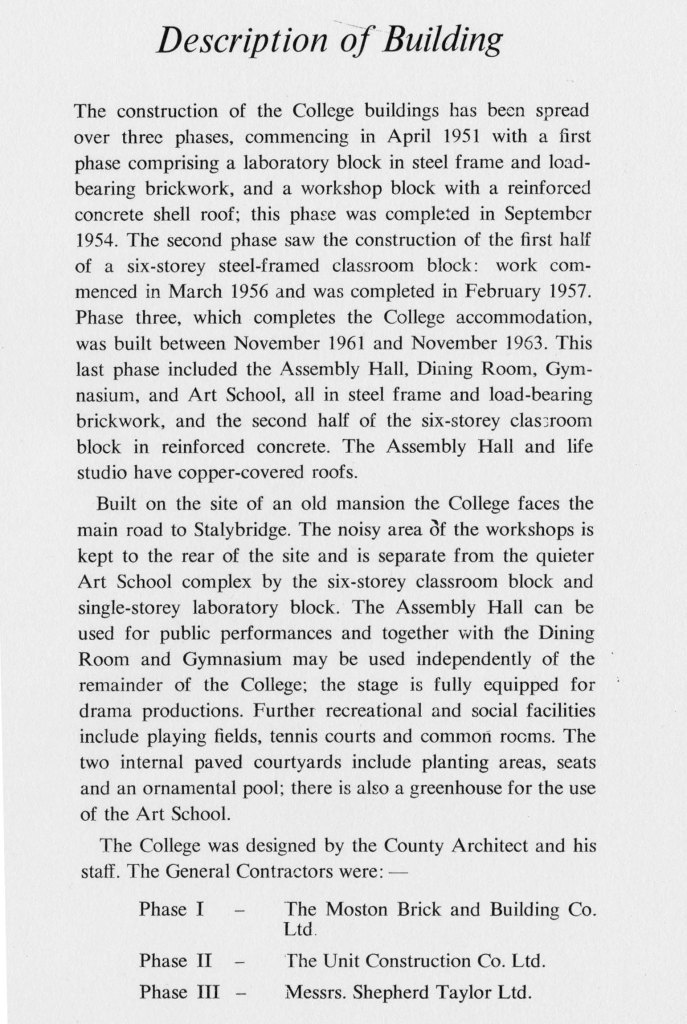

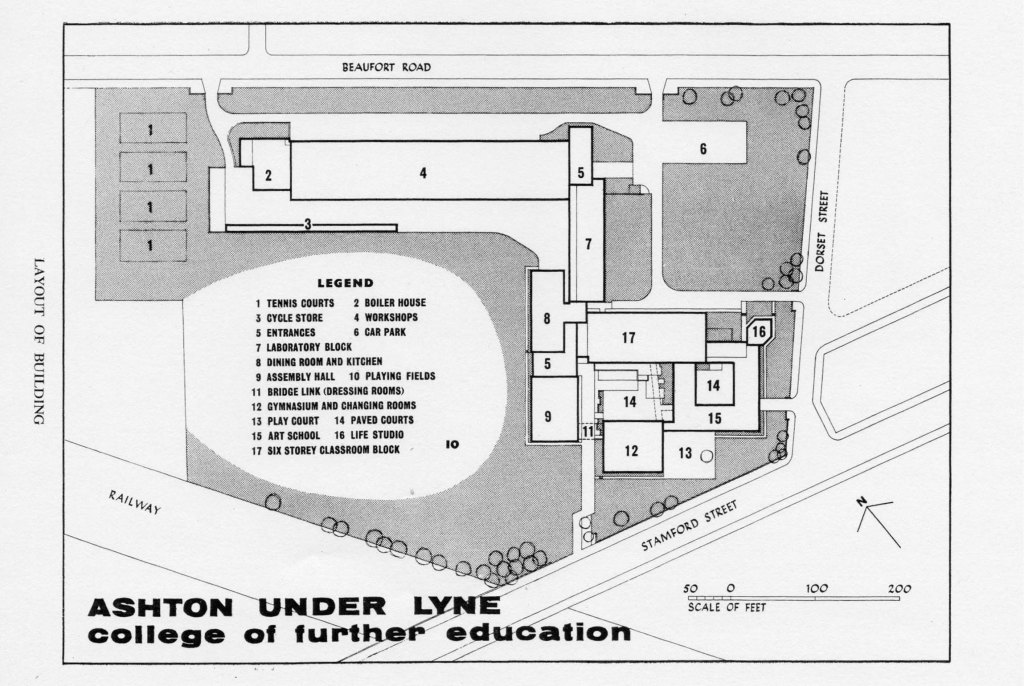

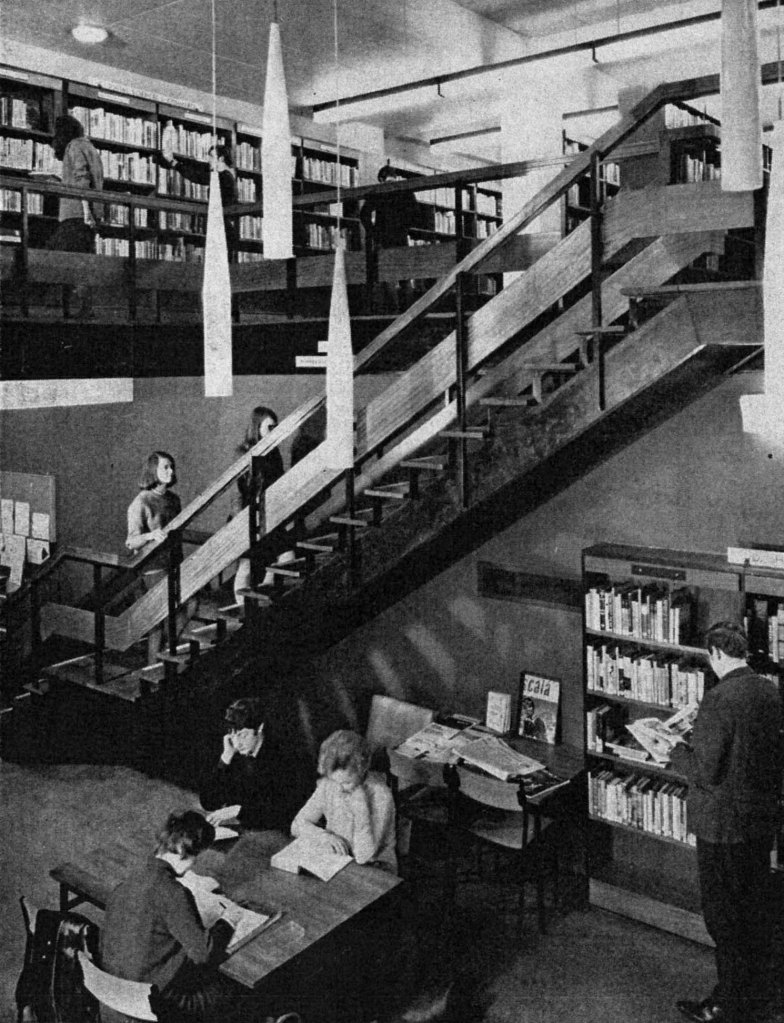

The college which I attended was opened on March 3rd 1964.

Gone were the autocratic Victorian stylings of the Heginbottom School – The College of Further Education represented a more open democratic age.

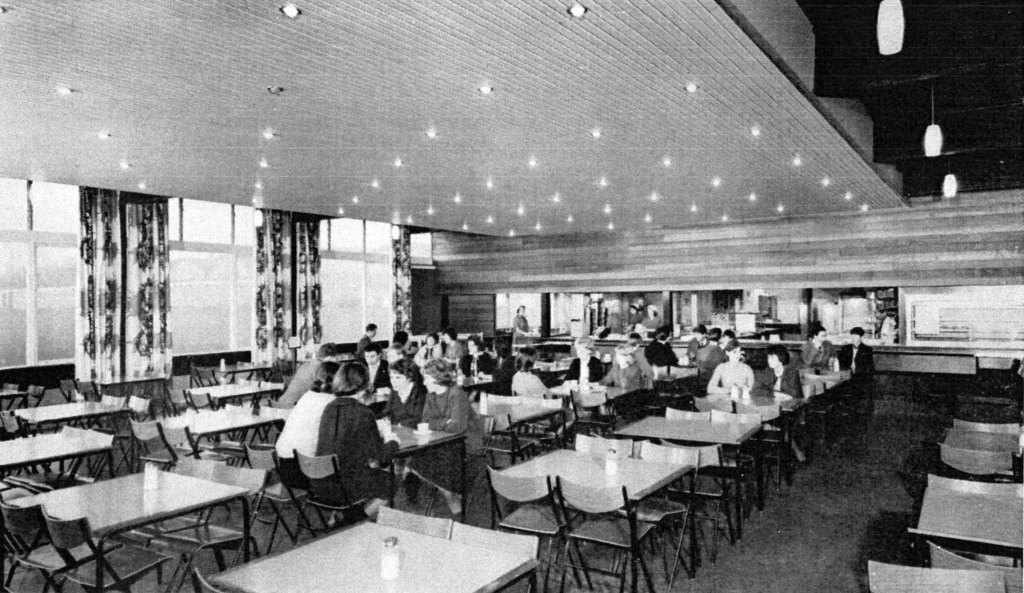

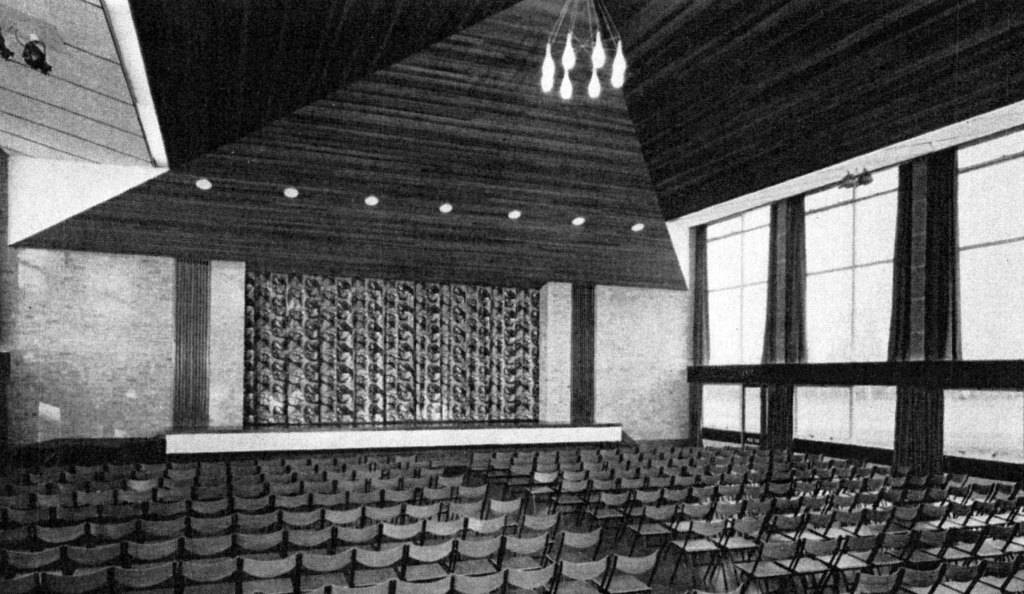

The communal areas were light and airy, with full-length windows, wooden floors, contemporary furniture and fittings.

The teaching rooms and workshops well equipped and staffed, with ample support from technicians and lecturers.

This was a no expense spared build – we were made to feel valued, in an institution purpose built for our education and future lives.

The full-time course was five full days a week, with one late evening for photography and art history.

I attended ever single day for two years, we were eager to learn and following an introductory merry go round of design disciplines, students were able to choose their own route.

I was privileged to have been taught by Bill Clarke as a student of Fine Art – of whom fellow Ashton student Chris Ofili said:

After six months on the foundation course I chose to specialise in painting and drawing. The teacher there, Bill Clarke, introduced me to painting in a way that didn’t make me feel restricted or limited. Not only was it something completely new, but it was something that allowed me to investigate further into who I am. He taught us that it wasn’t so much about painting a scene and making sure you got the shading right, but trying to get to a point where the thing that works is absolutely critical and essential to you as a living, breathing person. I was obviously aware of famous artists, but I suppose I never really thought that was what you could do with your life. He opened the door enough to make me think that it was worth going into the room.

Photo: Andy Duncan 2023

A huge emphasis was placed on observational drawing in the life-room, in addition to more exploratory work in a variety of media.

I also spent a great deal of time in the Print Room working in both etching and lithography with lecturer Colin Radcliffe.

Returning to the college four years ago, I found that the life room was now in use by the Animal Management course.

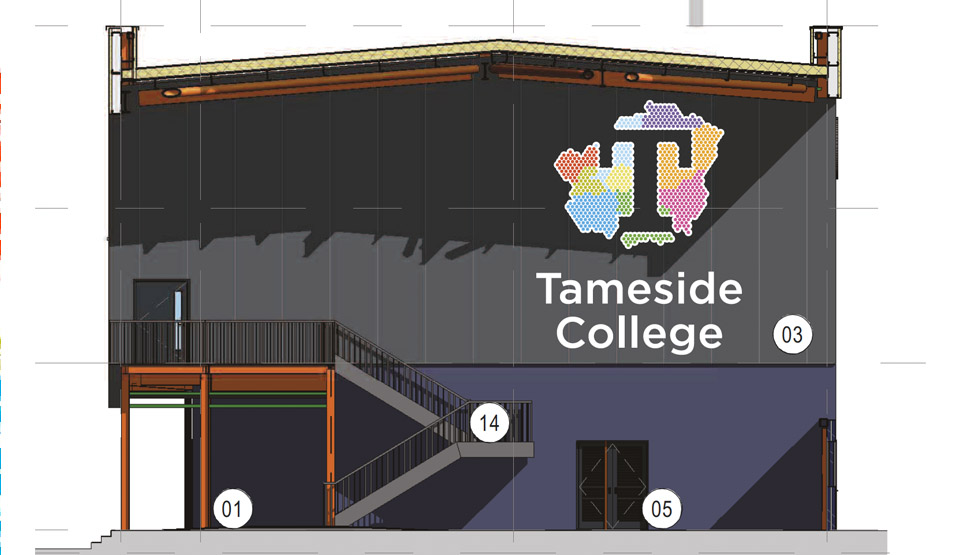

The site had been undergoing refurbishment and new development.

Built by Kier and designed by IBI Taylor and Young the Advanced Technologies Centre has been constructed following a £10.5 million investment.

Levolux designed, supplied and installed a customised architectural facade solution as part of the £10.5 million development of the Advanced Technologies Centre.

ITP supplied our VCL 250 vapour control layer as a protective solution underneath a stunning façade design. With a mono-filament reinforcement scrim for tensile strength, its polyethylene-based membrane ensures that the building envelope is properly sealed to control ventilation, prevent heat loss and protect insulates from interstitial condensation.

The single storey building was previously home to the Ceramics and Textiles rooms.

The Construction Skills Centre has been designed by Manchester-based architects 10 Architect.

Heckford Signs work with Willmott Dixon approached on a new coloured acrylic sign for the new Construction Skills Building at Tameside College. The aim for this new sign was to create a showcase of the college logo at an eye-catching size, to include 3D elements which would be housed on the East elevation of the impressive new building on campus.

The rolling curves of the original workshops have been retained and updated.

Since leaving the college in 1973, I graduated from Portsmouth Polytechnic with a BA(Hons) Printmaking, subsequently spending thirty years of my working life teaching in a variety of Further Educational sites across Manchester.

Fielden Park College seen here in 1973 – where I taught design to the printing apprentices.

Originally designed by the City Architect SG Besant Roberts in 1965, refurbished by Walker Simpson Architects.

Closed.

Wenlock Way – an annex of Openshaw Technical College, a former primary school which housed courses in Sign Writing, Jewellery, Horology and Retail Display.

Demolished.

Openshaw College – since demolished and rebuilt, becoming Central Manchester College in the 90s.

We were relocated to Taylor Street in the former Bishop Greer School – renamed the East Manchester Centre.

Since demolished to make way for an old people’s home.

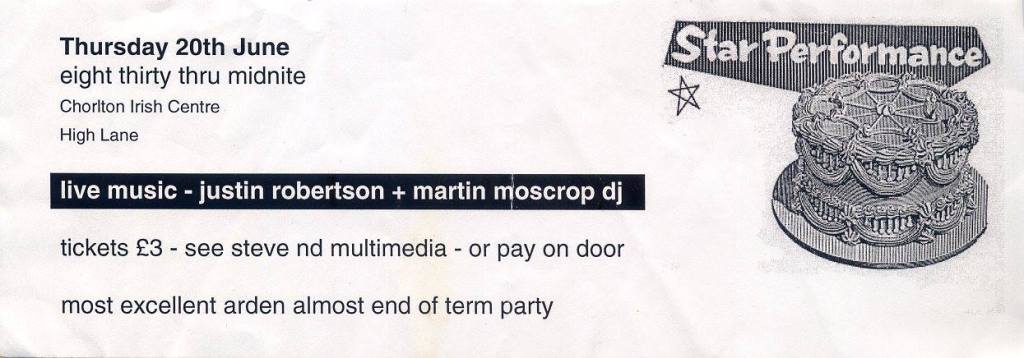

Following the reorganisation of Manchester’s FE provision we were moved again to the former Yew Tree High School, Arden Sixth Form College – renamed City College Manchester.

This block was eventually demolished to make way for the new Northenden Centre – which closed last year, which has in its turn been demolished.

Everyone was relocated to the brand new building on the former Boddington’s Brewery site.

Everyone but me, as I left in 2014 to become a modern moocher.

Manchester College City Campus

Following build completion in July, the long awaited 27,000 square metre, four-storey campus, designed by Bond Bryan and Simpson Haugh, offers a range of facilities, creating an exceptional student experience. It becomes the home of the College’s Industry Excellence Academies for Hospitality and Catering, Creative and Digital Media, Music, Computing and Digital as well as its Centres of Excellence for Visual Arts and Performing Arts.

It accommodates a range of Higher Education courses such as the UCEN Manchester’s School of Computing and Cyber-Security, The Manchester Film School and The Arden School of Theatre and the School of Art, Media and Make-up.

Things may come and things may go but the Art School Dance goes on forever.

My thanks to the Tameside Local Studies Centre for assisting me in accessing their archive material.