Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014 I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same on Ashton New Road.

Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014 I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same on Ashton New Road.

Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014, I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same.

1 Bank Street Bury Lancashire BL9 0DN

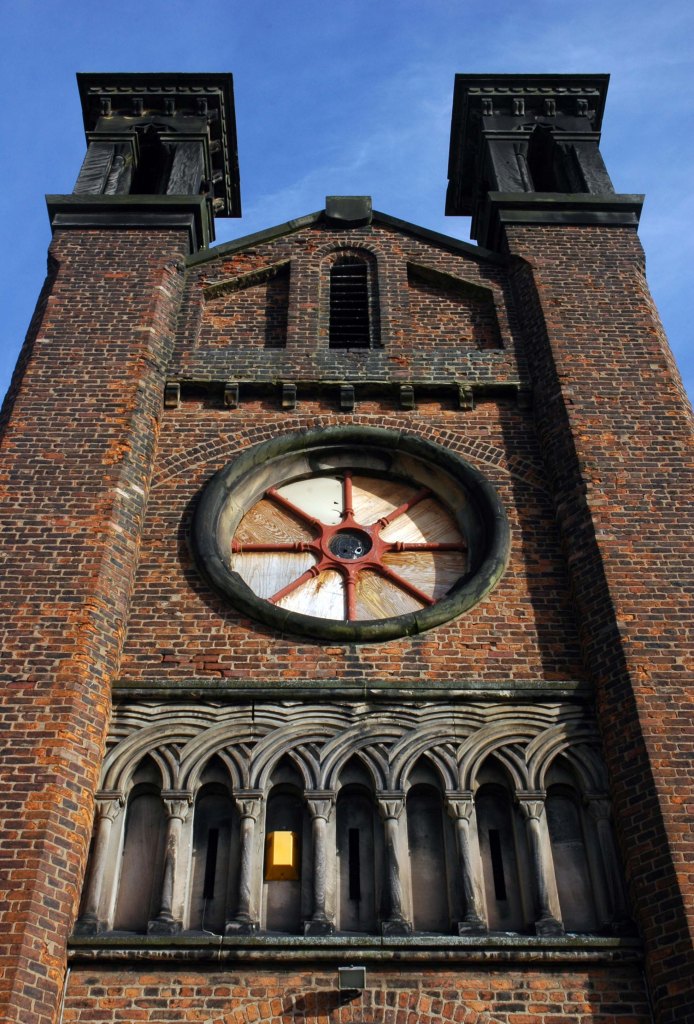

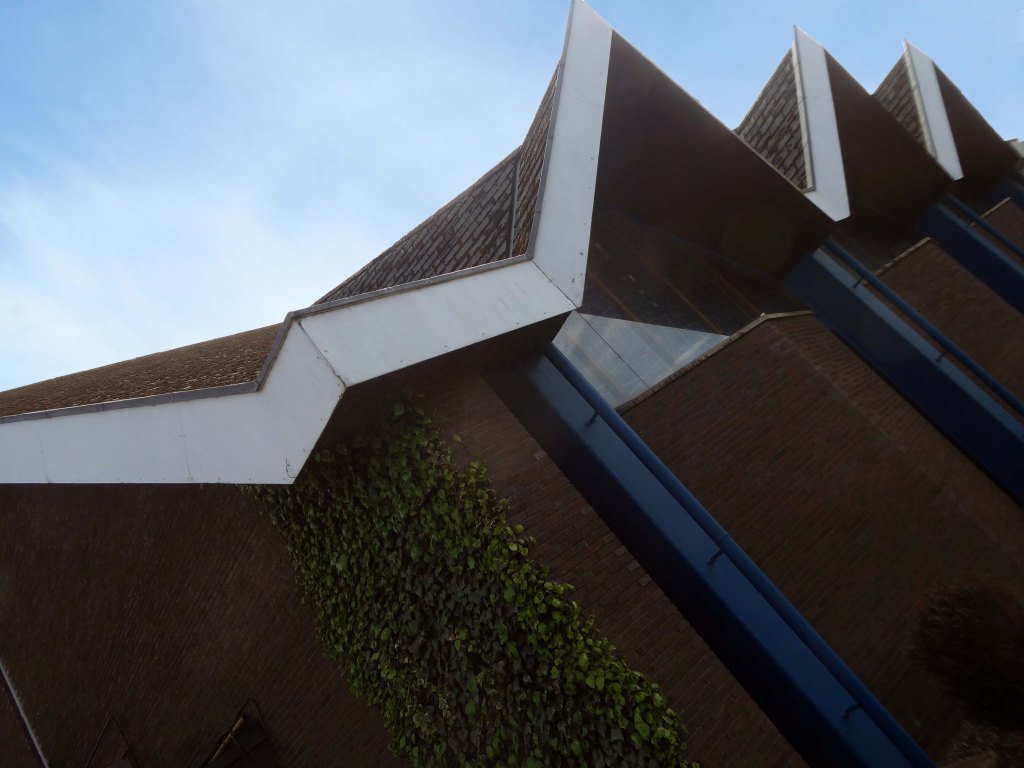

The new Bury Unitarian Church was designed and constructed by local architects James T Ratcliffe.

An interesting article was published at the time in Sacred Suburbs Portfolio, in which the church design was described as:

A well detailed, functional, yet flexible building.

The church was opened in 1974, with a service of dedication on Saturday, 9th March. The total cost, including furnishings, was £85,000 – It is now valued at about £1.5 million. The Churchwarden and Chairman of Trustees, at that time, was Bernard Haughton, who had succeeded Alex Rogers; he was to serve the Church in those capacities for the next 25 years. He was succeeded by Barbara Ashworth, our immediate past Warden. During this time, notwithstanding persistent problems with water leakage through its flat roof, the church continued to thrive and develop.

Enhancements have been made to improve the comfort and amenities of the building throughout the period with, for example, the installation of an improved heating – system, a sound – enhancement system in the church, and disabled access facilities including a lift to the upper floor. Through the efforts of Barbara Ashworth – past Church Warden, the proliferation of bequests, legacies and trusts which were complicating and restricting church-finances has been rationalised and the financial structure streamlined. Part of the land at Holebottom has been sold for development, and part has been upgraded as a public amenity.

The current congregation is still one of the best supported Unitarian Churches in the country and remains enthusiastic and committed to the Unitarian faith. There are many social groups including The Women’s League, The Men’s Fellowship, The Luncheon Club the Book Club and most recently, our Camera Club; coffee is served every Saturday morning – a session which welcomes members of the public to the church, some of whom have subsequently become church-members. Frequent social activities are organised by The Efforts Committee and are well-supported by the congregation and their friends and raise money in support of the activities of the church snd local charities.

The People Praising by Elizabeth Mulchinock is a 12 foot high original sculpture at the front of the church which represents the family of the church.

Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014, I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same.

Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014, I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same.

The A5103 is a major thoroughfare running south from Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester city centre to the M56 in Northenden. The road is two-lane dual carriageway with a few grade-separated junctions. It is used by many as a link to the airport and to the motorway network south.

The road starts at Piccadilly Gardens where it meets the A6. It heads along Portland Street – at one time it ran along the parallel Mosley Street, past fast-food outlets and off-licences and then meets the A34 Oxford Street. It multiplexes with that road north for 200 yards into St Peter’s Square and then turns left into Lower Mosley Street, initially alongside the tramlines and then past the former Manchester Central station, now a conference centre with the same name. The road becomes Albion Street and goes over the Bridgewater Canal and under the railway line east of Deansgate station. The road then meets the A57(M) Mancunian Way at a roundabout interchange. This is where most of the traffic joins and leaves.

The road is now 2×2 dual carriageway with the name Princess Road. It passes under the Hulme Arch, a grade-separated junction with the A5067, with an unusually large central reservation. This is presumably because of the proposed plans from the 1960s of a motorway. However, after passing under the junction, there are innumerate sets of traffic lights, with the B5219, the A6010 and the A5145, as well as many other unsigned roads. There are also many speed cameras set at 30 mph.

The road picks up pace as we exit the sprawl of South Manchester and the road becomes Princess Parkway, with a 50 mph speed limit. We cross the River Mersey and almost immediately hit the M60 at J5.

Except for the Manchester City Centre section – which was numbered A5068, this road did not exist on classification in 1922. Princess Road was built in 1932 to serve the new southwestern suburbs; initially it ran between the B5219 and A560 and was numbered B5290, with the road later extended north into the A5068 on the southern edge of the city centre and renumbered A5103.

The northern extension through Hulme initially followed previously existing roads, so followed a zigzag route. As part of the road’s upgrade and the reconstruction of Hulme in the 1970s the road was straightened and the original route can no longer be seen. The A5068 was severed around this time with the construction of the A57(M) and the A5103 took on its city-centre section, taking it to the A6.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road and Rochdale Road and Oldham Road and Ashton New Road and Ashton Old Road and Hyde Road and Stockport Road and Kingsway.

The road now begins slightly further south than it used to. Instead of starting on Fairfield Street in Manchester city centre, it begins immediately as the Mancunian Way ends, which at this point is the unsigned A635(M). The motorway flows directly into our route. There’s a TOTSO right at a set of lights, and we pick up the old alignment, which now starts as the B6469.

We can see the new City of Manchester Stadium on the left, site of the 2002 Commonwealth Games and now home to Manchester City FC. The road switches between S2 and S4 as it passes through the rather run-down urban areas of Ardwick and Gorton. A short one-way system at a triangular-shaped junction with the A662 leads onto a wider stretch as we near the M60 junction. This area is set to see significant industrial growth, with whole swathes of land either side of the now D3 road cleared and ready for development.

In 2014, having taken early retirement from teaching photography, I embarked on a series of walks along the arterial roads of Manchester.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road and Rochdale Road and Oldham Road and Ashton New Road

Starting at traffic lights on the A665 the road heads northeastwards, initially with the Metrolink on the left and a factory building on the right. The road then bears right at traffic lights marking the first section of on-street running for the trams, which lasts until just before a bridge over the River Medlock, after which the road passes to the south of the Sportcity complex whilst the tram line runs through the middle.

The A6010 is crossed at traffic lights, after which we see the tram lines on the left once more. We go over the Ashton Canal, then the tram lines at grade before bearing to the right to pass Clayton Park before another section of on-street running for the Metrolink begins, which continues for some distance. Just after crossing the Manchester city limit there is a set of traffic lights, after which the road becomes D2 for a short distance to allow a tram stop – Edge Lane, to be located in the central reservation. The tram leaves the road to the right for the next stop – Cemetery Road, and the stop in Droylsden town centre is once again in the central reservation. In all three cases the street running recommences after the stop.

In 2014, having taken early retirement from teaching photography, I embarked on a series of walks along the arterial roads of Manchester.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road and Rochdale Road and Oldham Road.

The A62, which runs from Manchester to Leeds, via Oldham and Huddersfield, was once the main route across the Pennines, connecting the largest city in Lancashire with Yorkshire’s largest city. However with the completion of the M62 towards Leeds in the early 1970s it lost much of its importance and traffic to the motorway, which runs a few miles to the north. These days, the A62 serves as a busy primary route between Manchester and Oldham, an extremely very quiet route over the Pennines, and then a fairly busy local road linking Huddersfield with Leeds.

Most maps show that the A62 starts its journey in the middle of Manchester by leaving the A6 Piccadilly and running along Lever Street – the original route was the parallel Oldham Street. However, owing to a bus gate Lever Street is not generally accessible from Piccadilly. We head out easterly on a busy street – non–primary, until we meet the Ring Road where we pick up primary status that we retain until Oldham. We turn left at this point and then immediately right to start the A62 proper.

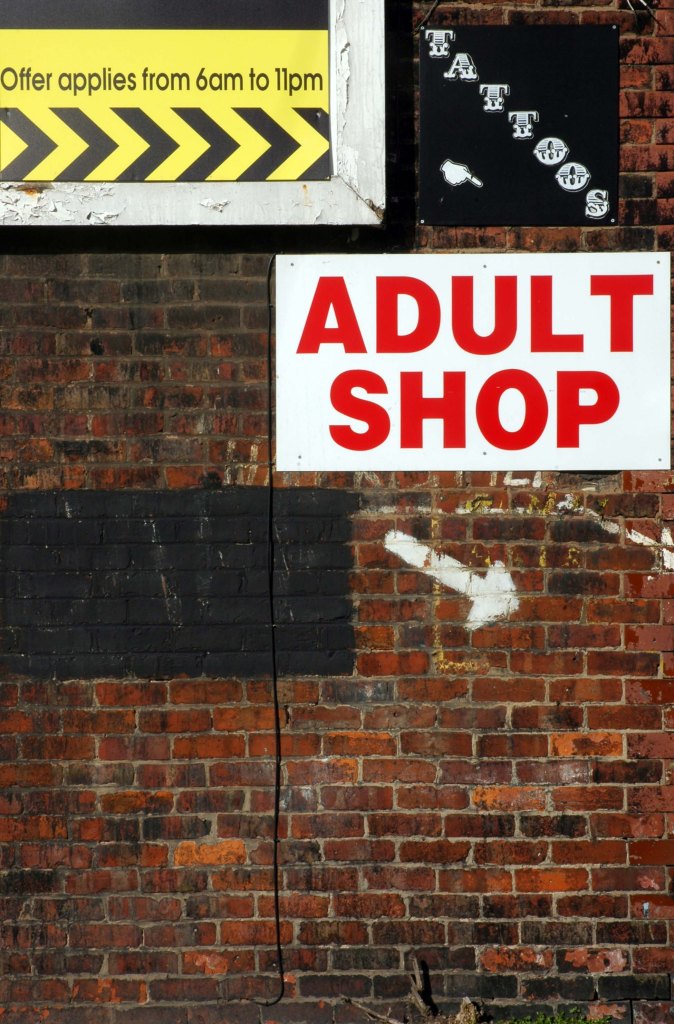

In 2014, having taken early retirement from teaching photography, I embarked on a series of walks along the arterial roads of Manchester.

This whole undertaking was prompted in part by Charlie Meecham’s 1980’s Oldham Road project .

The work questions whether a sense of local identity can be maintained in an area of constant redevelopment and community displacement.

This area was first developed in the 19th century for cotton manufacture, coal extraction and later electrical and heavy engineering. The road was lined with shops and there was a vibrant community.

When I first started working on the project, most of the early industry had ceased operating and the mills were either abandoned or being dismantled. However, some had been refurbished either for new industrial use or later, made into apartments. Some run down areas were cleared making way for new housing. Clearance also provided opportunity to build new schools, trading estates and create green space. Most of the older community centres such as theatres and cinemas along the road were also abandoned and later cleared.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road and Rochdale Road and Ashton New Road and Ashton Old Road and Hyde Road and Stockport Road and Kingsway and Princess Parkway.

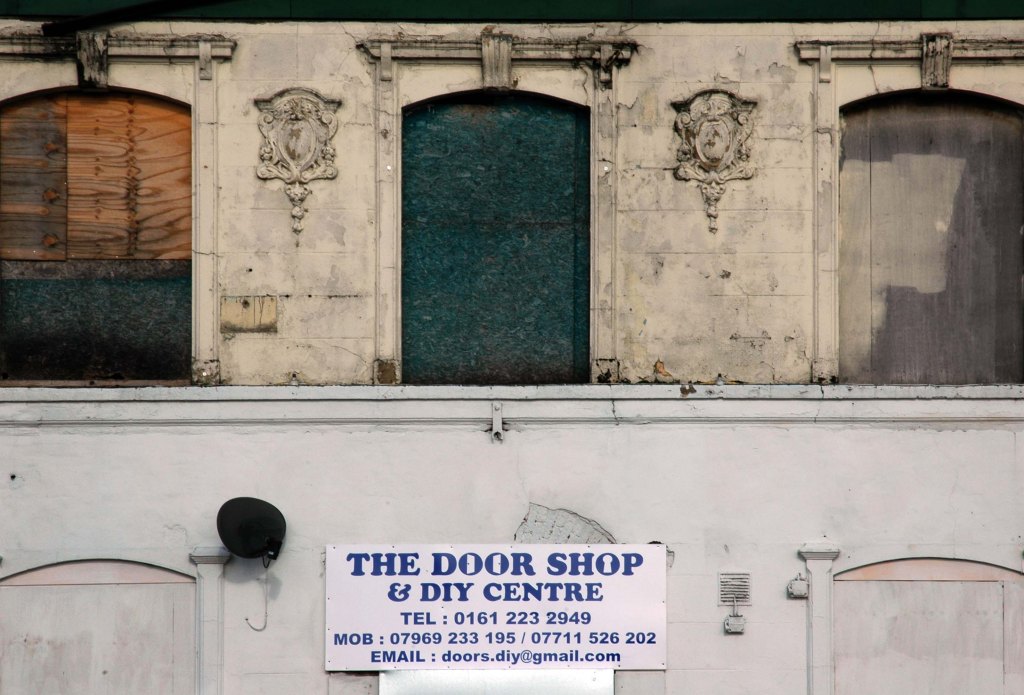

The obvious place for the A664 to start is on the A665 Manchester & Salford Inner Relief Route, which at this point is actually two parallel one-way streets. However, many maps show the road continuing a short distance into the city centre to end at traffic lights by the Shudehill Interchange – this is presumably for historic reasons: the road originally continued along the High Street to its terminus on the A6 Market Street.

The road heads northeastwards through the suburbs, the street name Rochdale Road, already emphasising its destination. Initially dual, the road narrows just before crossing the bridge over the railway line east of Victoria station. It continues through Collyhurst and widens again just before crossing the A6010 Intermediate Ring Road, which here is made up of two parallel one-way streets, requiring two separate sets of traffic lights to cross.

Now non-primary – but still dual for a short distance more, the road runs in a more northerly direction through Blackley, where it becomes wooded for a short distance as it passes the Boggart Hole Clough park. Slightly further on the road has been straightened, after which it bears right to widen considerably and cross the A6104 at traffic lights just before M60 J20, which only has west-facing sliproads. The road narrows again on the far side of the motorway and leaves Manchester for Rochdale at the same point.

In 2014, having taken early retirement from teaching photography, I embarked on a series of walks along the arterial roads of Manchester.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road.

Available online here or call in the Modernist Shop on Port Street Manchester.

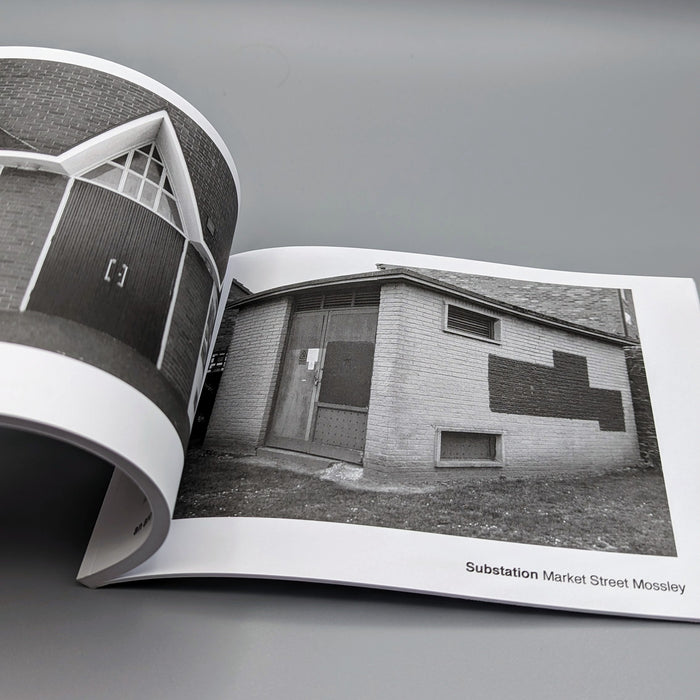

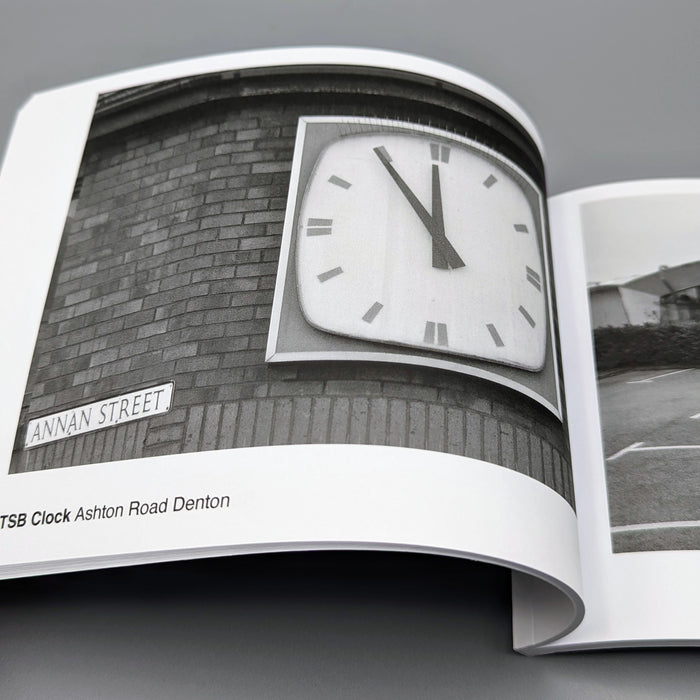

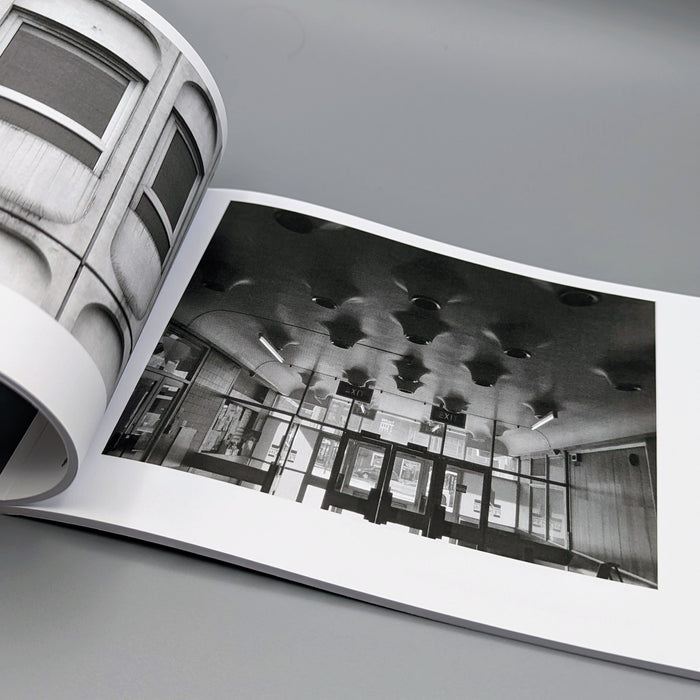

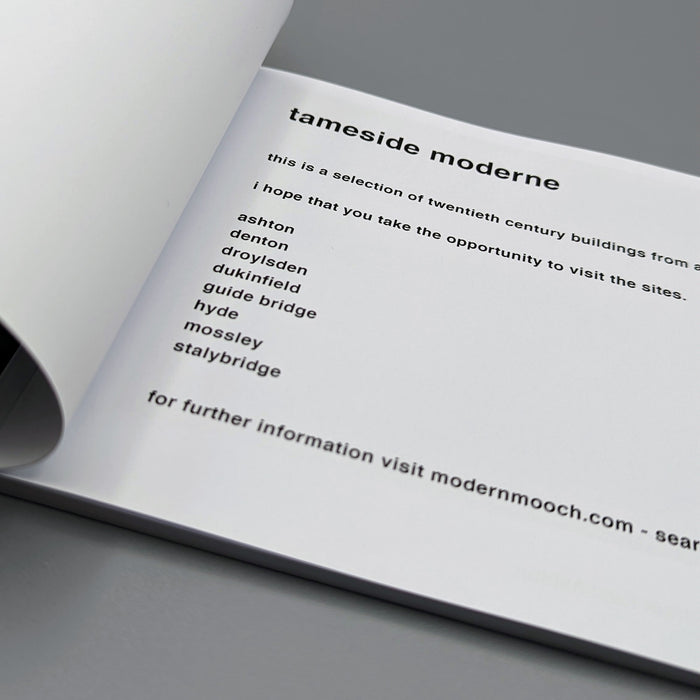

Tameside Moderne

By Steve Marland

A comprehensive guide to the Borough’s modern architecture.

Almost two years in the making.

Tameside east of Manchester – a volcanic explosion of concrete, glass, steel, brick and wood!

From sacred sites to suburban substations, a rollercoaster ride through provincial style.

Softcover, 84pages,

B&W

148 x 210xmm – landscape

£10 well spent – be quick these will fly!

Architects: Austin Smith Lord

We begin at the Railway Station – recently refurbished, overwriting its 60s iteration – completely rebuilt by the architect Ray Moorcroft as part of the modernisation programme which saw the West Coast Main Line electrified.

Across the way an enormous brick clad multi-storey car park – skirted by the lines for the tram, which travels to and from Birmingham.

Walk across the brand new pedestrian footbridge over the ring road.

Architectural glass artist Kate Maestri was commissioned to produce the artwork design which features glass with blue and green strips of colour running through it.

Architects: Austin Smith Lord

Linking the Rail Station with the brand new Bus Station.

The normal practice of the Wolverhampton Bus Service is to have dirty, smelly buses, that are cramped and extremely hot in the summer and freezing cold in winter. They offer no announcements apologizing for delays they know about and don’t appear to care how long passengers wait with no idea of how or when they’ll be getting a bus.

The best thing you can do is learn to drive as quickly as possible and get your own vehicle or car pool.

Architects: Austin Smith Lord

Onward now to the Express and Star Building – Grade II listed.

Architect: Marcus Brown 1934.

The building is faced in a reconstituted Hollington stone called Vinculum, produced by another local firm, Tarmac.

A plaque commemorates RJ Emerson, art teacher and sculptor who sculpted Mercury in 1932.

Wolverhampton History and Heritage Society

Midland News Association managing director Matt Ross confirmed the company is now looking at the building’s future.

For a number of years we have been exploring opportunities surrounding our historic Express & Star offices in the heart of Wolverhampton.

After removing the printing presses from the site and restructuring our departments we now have significant spare capacity available and so are looking at the various options available to us, be that redeveloping the current site or exiting the building altogether.

Extension is by architects: H Marcus Brown & Lewis 1965

With further work at the rear.

Along Princess Street this corner group, with an impressive clock tower – originally HQ for the South Staffordshire Building Society

Architects: George A Boswell of Glasgow 1932.

On to the Mander Centre – opened on 6th March 1968, refurbished 1987, 2003 and 2016-17.

The Mander Shopping Centre in the heart Wolverhampton is your one-stop shopping destination for all things fashion, home, beauty, food and technology.

Architects: James A Roberts principal architect Stanley Sellers.

Developed by Manders Holdings Plc, the paint, inks and property conglomerate, between 1968 and 1974. The site occupies four and a half acres comprising the old Georgian works and offices of the Mander family firm, founded in 1773, as well as the site of the former Queens Arcade.

The Wulfrun Shopping Centre is an adjacent companion to the Manders development.

The Wulfrun Centre was built as a result of a joint project between Wolverhampton Council and the Hammerson Group – open for business in October 1969.

Piazza postcard 1970.

Architects: T & PH Braddock and also Bernard Engle & Partners.

Along St Georges Parade, an abandoned Sainsbury’s church combo – store designed by J Sainsbury’s Architects Department opened 1988.

The church was built between 1828 and 1830 – architect: James Morgan, at a cost of £10,268. It was consecrated on Thursday 2 September 1830 by the Bishop of Lichfield, it was made redundant in 1978.

The site is currently under lease to Sainsbury’s for a further three years and will come forward on a phased basis subject to their lease concluding. The council is in active dialogue with prospective development partners on the redevelopment of this site and in wider consultation with Homes England.

Back tracking to the Combined Court Centre.

Architects: Norman and Dawbarn 1990

Notable cases included trial and conviction of four members of The Stone Roses, in October 1990, for criminal damage to the offices of their former record company.

Thence up Snow Hill to the former Citizens Advice former Barclays Bank currently empty.

Architects: John HD Madin & Partners 1969

Take time to have a look around the back.

Off to Church Street and Telecom House

Sold for £4.25 million to Empire Property in 2022.

It had previously been sold for more than £3m in July 2018, also for use for apartments, to Inspired Asset Management which later went into receivership.

Located on a popular apartment block on Church street in the Wolverhampton centre, this 1 bedroom property has been newly renovated throughout and compromises an entrance hallway, open plan lounge/kitchen with in built appliances, shower room and double bedroom.

£650 PCM – Connells

Next to this modern piazza New Market Square – Architects: Nicol Thomas from a concept by head of planning Costas Georghiou.

Formed from the former Market Square, a mix of flats and shops opened in 2004, in an Italianate version of the modish school of streaky bacon.

In 2021 the Coca-Cola Christmas Truck visit to the Midlands was cancelled.

It was meant to arrive at Market Square in Wolverhampton at 11am today but failed to show up.

One fan had waited since 7am this morning to see the Coca-Cola truck.

While schoolchildren were left gutted when the truck didn’t turn up – and one boy had been so excited his mother said he had been talking about the red truck all morning.

Retail Market – Late 1950s market hall and offices above.

Architects: Borough Surveyor.

Excellent example of the Festival of Britain style of architecture, won Civic Trust Award 1960.

Locally Listed March 2000.

demolished January 2017.

Photo: Roger Kidd

This development that wraps itself around Salop, Skinner and School Streets appears to be of a similar period to the Retail Market – and sports a Lady Wulfrun in relief.

There is access to its roof top car park.

And also an exit back to street level.

Where we find at street level the former Odeon Cinema, opened on 11th September 1937 with Conrad Veidt in Dark Journey.

Architects: PJ Price and Harry W Weedon.

In October 2000, the former Odeon was designated a Grade II Listed building by English Heritage.

RIBA pix

In recent years it was a Mecca Bingo Club, but this was closed in March 2007 In October 2009, it had been refurbished and re-opened as the Diamond Banqueting Suite. In April 2021 police raided the vacant building to discover an illegal cannabis farm operating in the building.

Four men were arrested.

Let’s take a turn around the corner to Victoria Street where we find the complex of Beatties Buildings.

Architects: Lavender, Twentyman and Percy 1920’s – 30’s

The C20 Beatties store is a multi-period site developed first in the 1920s-30s. A Burton’s men’s clothes shop was built on a curved corner site at Victoria St/Darlington St and Beatties themselves replaced their existing Victoria St store in the 1930s with a building by local architects Lavender, Twentyman and Percy. Beatties later acquired and incorporated the Burton’s shop into their store. These two buildings form the locally listed building to which were added a mid-C20 extension along Darlington St and a late-C20 development to the rear at Skinner St.

An imperious Portland stone clad mixed us block on Waterloo Road, with a delightful clock.

Formerly the Gas Showrooms then Sun Alliance & London Insurance offices – aka Clock Chambers

The showroom in Darlington Street was also the centre of a radio network that controlled a fleet of service vans. This enabled customers to receive service within minutes of making a telephone call. Demonstrations of cookery, washing and refrigeration were given by the Gas Board’s Home Service Advisers and a number of the company’s engineers, who specialised in designing gas equipment for industrial processes operated an advisory service for manufacturers.

Architects: Richard Twentyman 1939.

Nineteen Waterloo Road latterly First City House formerly home to Eagle Star Insurance 1970

8-10 Waterloo Road architects: Richard Twentyman 1959 extended 1966.

31 Waterloo Road – Waterloo Court architects: Kenneth Wakeford, Jerram & Harris 1972

Right turn to the Telephone Exchange

Architects: NHA Gallagher of the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works and Clifford Culpin & Partners job architect Leslie Parrett 1971.

Around the bend to The Halls – once the Civic Halls.

Architects: Lyons and Israel 1936-38

Refurbished 2003 by Penoyre & Presad with more alterations in 2021 by Jacobs consulting engineers.

RIBA pix – 1939

Over the road to the Civic Centre.

Architects: Clifford Culpin & Partners 1974-79.

We end our Wolverhampton wander at the College of Art and Design

Architects: Diamond Redfern and Partners with A Chapman Borough Architect 1969

Huge thanks to Tom Hicks aka Black Country Type for his invaluable assistance.

Plas Newton Ln Chester CH2 1SA

Architect: LAG Prichard – Son & Partners 1964/66

I caught the 51 Bus from the Bus Exchange – and the ever so helpful fellow passengers put me off at the right stop.

The church is set back from the road and sands in substantial grounds – visible through the surrounding houses.

A large site at the corner of Plas Newton Lane and Newhall Road was acquired, and a new church designed by the architects LAG Prichard, Son & Partners. The design embodied the ideals of Vatican II, with no seating more than fifty feet from the altar. It was designed for 675 people. The foundation stone was laid in September 1964 by Canon Murphy, and the 115 ft spire lowered into position in December 1964. The first Mass was on 19 December 1965, and the church was officially opened in 1966 by Bishop Grasar. St Columba was the third new Catholic church to be built in Chester after the Second World War.

The only glazing to survive from the original church scheme is small triangles of glazing on the sanctuary elevation and the dalle de verre-style baptistery window by Hans Unger & E Schulze.

Unger & Schulze ran a prominent mosaic and glass studio in London from 1960-74, and provided a large mosaic for another LAG Prichard church in 1965, St Jude’s in Worsley Mesnes – Wigan.

The coloured glazing depicting St Columba, Christ and the apostles was added in 1986.

It is such a striking and dynamic church – angular, very angular.

Let’s take a good look around and about.

13 Swinton Park Rd Salford M6 7WR

It was decided to build a new church in 1963, when the architects Burles, Newton & Partners were appointed and drew up a scheme for a church seating 470. Financial restraints delayed the start of building work until 1966. The contractors were William Thorpe and the foundation stone was laid by Bishop Burke in October 1967. The church was opened two years later in 1969. The church was built to reflect the emerging liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council, with a wide interior affording full views of the altar. The same architects designed a presbytery, added in 1974-5. A sanctuary reordering took place at some point when the Blessed Sacrament Chapel became the Lady Chapel and the tabernacle was placed behind the altar. The altar rails were removed, and the sanctuary carpeted. Perhaps at the same time the font was brought from the baptistery into the body of the church.

Description

All orientations given are liturgical. The church is a steel-framed structure with loadbearing gable walls built on a series of rafts to guard against mining subsidence. It was designed to ensure that the congregation would have unimpeded views of the sanctuary, and the architects described the layout as ‘in conformity with the Spirit of the new Constitution’. The plan is near rectangular, angled at the east end, with a striking roof swooping up at the east end and trios of sharply pointed gables on each side.

The building is entered on the northwest side via a low porch which gives to a narthex and a former baptistery lit by a pyramidal roof light, attached on the west side. Light pours in to the narthex from a screen with semi-abstract stained glass with the ox symbol of St Luke, an original fixture. The nave is an impressive and memorable space with the boarded roof forming dramatic shapes which frame the east end and sanctuary, where a pair of full-height slit windows are angled to cast light without creating glare and frame a Crucifix. The roof rises up on each side of the big triangular windows on the north and south sides. Those to the south have stained glass showing the Tree of Life the True Vine and the Cross of Faith designed by Roy Coomber of Pendle Stained Glass in 2002-3. There is a cantilevered west gallery with a pipe organ set into the wall above it and a southeast chapel, now a Lady Chapel, formerly of the Blessed Sacrament, with stained glass on sacramental themes. A Pietà in the chapel probably originated in the previous church. The tabernacle, of stainless steel with high relief abstract modelling, was repositioned behind the altar at the time of the reordering. This item and the sanctuary Crucifix with a gilded figure are by an unknown artist. Stations of the Cross are by Harold Riley, installed in circa 2003. They consist of triptychs executed in pencil and wash. Other works by Riley include a study of the Virgin dated 2003 and a print of his painting Our Lady of Manchester.

I had a very brief moment in time to photograph the interior in very low light.

But a little more time to wander around outside.

St David’s – 1 Penrhyn Beach East Penrhyn Bay Llandudno LL30 3NT

This church was built in 1963 to a design by Rosier and Whitestone of Cheltenham, to replace a wooden church of 1929.

I had previously cycled by on one of my tours of North Wales – stopping to snap the elegant exterior.

On this occasion I contacted the church to arrange access to the interior – the building is open from 10.00 – 12.00 most weekdays.

The church has been recommended for listing in this CADW report on post war architecture in Wales.

St David’s deserves listing, a distinctive building with a remote slate clad campanile.

The interior does not disappoint, a light and airy space with confident curved wooden roof struts and clear angled arched windows.

My thanks to the kindly parishioner Alan, who made me more than welcome on the day of my visit.

Sadly the bell is no longer seated – its shell cracked and the wooden support rotted away.

Let’s take a look inside.

The organ pipes are purely decorative – the current console being digital.

Thanks again all for your time and informative conversation.

I was last here in 2020 – made ever so welcome in this Byzantine cathedral like church.

The apsed sanctuary is completely covered in a mosaic scheme with the theme Eternal Life designed by Eric Newton. Newton was born Eric Oppenheimer, later changing his surname by deed poll to his mother’s maiden name. He was the grandson of Ludwig Oppenheimer, a German Jew who was sent to Manchester to improve his English and then married a Scottish girl and converted to Christianity. In 1865 he set up a mosaic workshop, (Ludwig Oppenheimer Ltd, Blackburn St, Old Trafford, Manchester) after spending a year studying the mosaic process in Venice. Newton had joined the family company as a mosaic craftsman in 1914 and he is known to have studied early Byzantine mosaics in Venice, Ravenna and Rome. He later also became art critic for the Manchester Guardian and a broadcaster on ‘The Critics’. Newton started the scheme in 1932 and took over a year to complete it at a cost of £4,000. It had previously been thought that he used Italian craftsmen, but historic photographs from the 1930s published in the Daily Herald show Oppenheimer mosaics being cut and assembled by a Manchester workforce of men and women. It is likely, therefore, that the craftsmen working on St John the Baptist were British.

There had, as ever, been issues with the structure, water ingress and such, given several flat roofs and a temperamental ferro-concrete dome.

Happily, a successful Lottery Heritage Fund grant has covered the cost of two phases of repair to the physical fabric.

Thanks to the Parish Team, for once again making us all feel so welcome, and thanks also for their efforts in securing the finances which have made the restoration possible.

We were all issued with our hard hats and hi-vis at the comprehensive and informative introductory talks.

Followed by a detailed explanation of the mosaic work being undertaken by Gary and his team from the Mosaic Restoration Company.

This involves skilfully cleaning the whole work, whilst repairing and replacing any damaged areas.

We were then privileged to ascend the vast scaffold, the better to inspect the work up close and personal.

And this is what we saw.

Many thanks again to our hosts, the contractors and all those involved with this spectacular undertaking.

By wandering aimlessly, all places became equal, and it no longer mattered where he was.

Paul Auster City of Glass.

The station as built in 1961 to a design by the architect William Robert Headle, which included and advertised a significant amount of the local Pilkington Vitrolite Glass. The fully glazed ticket hall was illuminated by a tower with a valley roof on two Y-shaped supports. The platform canopies were free standing folded plate roofs on tubular columns.

The new station building and facilities were assembled just a few yards from the 1960s station building and is the third build on the same site. The project came in at a total estimated cost of £6 million, with the European Union contributing £1.7 million towards the total funding. The new footbridge was lifted into place in the early hours of 22 January 2007.

The striking Pilkington’s glass-fronted building was designed by architect SBS of Manchester. Construction work was completed in the summer, with the new waiting rooms and footbridge opened to passengers on 19 September. The new station building was officially opened on 3 December 2007.

Emerging from the space age bubble of St Helens Central Station.

Turn right towards The Hippodrome

In the early Edwardian era a fine theatre was opened on 1st June 1903. It had been designed by local architect J A Baron and was on the site of an earlier theatre known as the Peoples Palace. It was operated as the New Hippodrome Cinema from 8th August 1938 when it reopened with Anna Neagle in Victoria the Great. On 1st September 1963 it was converted to a Surewin Bingo Club by Hutchinson Cinemas which continued to operate in 2008. By May 2019 it was independently operated as the Hippodrome Bingo Club.

Onwards down Corporation Street to Century House, currently awaiting some care and attention and tenants.

Century House is a prominent landmark in St Helens town centre, being the tallest office building in place. The accommodation ranges over 9 floors, providing offices from a single person, to whole floors. In addition, all tenants benefit from the use of a modern break out space and meeting rooms, in addition to manned reception desk.

Next to the Courthouse low lying, lean and landscaped.

Further on down the road the former Unitarian Chapel – now the Lucem House Community Cinema.

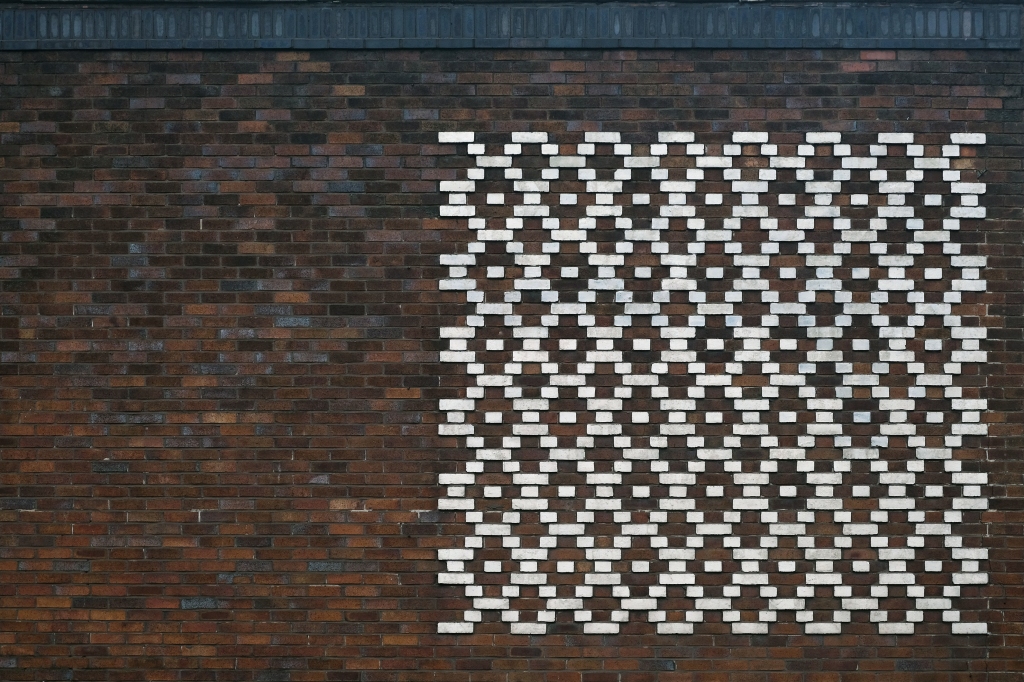

On the corner the YMCA offers a cornucopia of architectural styles and fun.

Including this geometric brick panel.

Around the corner to the Police Station by Lancashire County Architect Roger Booth.

Down the way the derelict Job Centre.

There are plans afoot for conversion to apartments.

Former Capitol Cinema.

Architects: Frederick Evans and Edwin Sheridan Gray

The Capitol Cinema opened on 3rd October 1929 by an independent operator. It stood on a prominent corner site at North Road and Duke Street – known as Capitol Corner.

The Capitol Cinema was taken over by Liverpool-based Regent Enterprises Ltd. in 1929, and by the Associated British Cinemas – ABC chain in 1935. It underwent a renovation in the 1960’s, and was closed by ABC on 9th December 1978.

The building was converted into a sports centre, by 2009 it was a Central Fitness gymnasium.

Along the way to St Mary Lowe House RC – the style is a combination of Gothic and Byzantine elements. One of the most unusual fittings is the carillon, one of the largest in the British Isles with 47 bells, which was installed in 1930 and is still played regularly.

Architect: CB Powell 1924-30 Grade II Listed

Next to the Ormskirk Street United Reformed Church

Ken Fisher’s first APEC project 1976

The main approach is identified by a beak-like porch which projects from the main cladding. In this space hangs a recast eighteenth century bell, from the original chapel.

Let’s take it to the Midland, Nat West and Barclays Banks.

With an intermediate former Gas Showroom.

Next to the Church of St Helen.

Architect: WD Caroe 1920-26 Grade II Listed

A chapel has been on the site since at least the 16th century. The chapel was doubled in size in 1816, but burnt down in 1916. It is the parish church of the town, and stands in a prominent position.

St Mary’s Car Park a multi-storey masterpiece straight outa Dessau.

Next crossing a complex web of inner ring roads designed with the beleaguered pedestrian at the forefront of the planners’ minds.

To the inter-war Pilkington’s Offices – Reflection Court

Architects: Herbert J Rowse and Kenneth Cheeseman 1937-41 Grade II Listed.

Onwards to the Post office – sorted.

Wellington Road Eccles M30 9AL

Architect: TD Howcroft 1969

Once upon a time there was a Gothic church.

The Cornerstone of the building was laid in front of a crowd of 2,000 on Good Friday 1859 and the church was opened for public worship on Good Friday 6th April 1860. In the press of the day, the church was described as – a Cathedral looking church.

In 1965 it was announced that a new Eccles motorway would be built through the church land.

Work began to demolish the Church and replace it with a new smaller church, but the old church did not go down without a fight as workers could not pull down the steeple. After eleven days of battering and buffeting by eighteen pounds of gelignite and two eight ton bulldozers, the steeple finally surrendered.

Then there wasn’t – then there was this:

On Friday 11th July 1969, the new church officially opened with a splendid ceremony. A minor hitch occurred when the organ blew a fuse during the second verse but the Congregation sang through it while organist Mr Kenyon frantically fumbled about and rectified the matter.

TD Howcroft was also responsible for St Wilfrid’s in Pevensey Bay – I happened to cycle by in 2015.

My thanks to Mr Tony Flynn – the acting Lord Mayor of Eccles, for arranging our visit through church member Mr George Cross.

To the rear the exterior is, as Mr Pevsner would say – unprepossessing.

The elevation facing the main road more than somewhat less unprepossessing.

A curved apse along with a raised and canted roof – a window up above illuminating the altar.

The main body of the church is bold and voluminous – strong verticals to the rear and right.

The pews, organ pipes and other furnishings appear to be of a piece.

There is a dynamic timber roof with supporting beams.

Previous Pastors.

Relocated War Memorials.

Broomfield Rd Sheffield S10 2SE

Having been here before – I returned.

There is something within the work of George Pace which speaks directly to my eyes and heart – and feet. His Modernism is tempered by the Mediaeval – along with Arts and Crafts references and a nod to Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp

I have also visited Bradford, Chadderton, Doncaster, Keele and Wythenshawe.

Here in Sheffield is a church built in 1868 – 1871 to a standard neo-Gothic design by William Henry Crossland. Bombed in the Blitz restored, redesigned and built by Pace 1958 – 1963, accommodating the original spire and porch.

Here is the Historic England listing.

There is stained glass to the east, Harry Stammers illustrating the Te Deum and to the west an abstract design by John Piper made by Patrick Reyntiens.

The laddered design glass in the side chapel, is by Gillian Rees-Thomas.

Let’s take a walk around the exterior.

Time to go inside – happily the St Mark’s is open weekdays, in addition to Sunday services.

759 Argyle Street Glasgow G3 8DS

Architects: Honeyman, Jack & Robertson

I was walking along St Vincent Street one rainy day.

From the corner of my left eye, I espied a pyramid.

Curious, I took a turn, neither funny nor for the worse, the better to take a closer look.

Following a promotion within the Church of Scotland to construct less hierarchical church buildings in the 1950s, an open-plan Modern design with Brutalist traits, was adapted for the new Anderson Parish Church. The building consists of a 2-storey square-plan church with prominent pyramidal roof, with over 20 rooms. The foundation stone was laid in 1966, with a service of commemoration in the now demolished St Mark’s-Lancefield Church. The building was completed in 1968.

Let’s take a look around outside.

Later that same day, I got a message from my friend Kate to visit her at the centre.

She is charged with co-ordinating a variety of activities at The Pyramid.

In 2019 the Church of Scotland sold the building and it became a community centre for people to:

Connect, create and celebrate.

It also serves as an inspirational space for music, performances, conferences and events.

Let’s take a look around inside.

As a footnote the recent STV Studios produced series SCREW was filmed here!