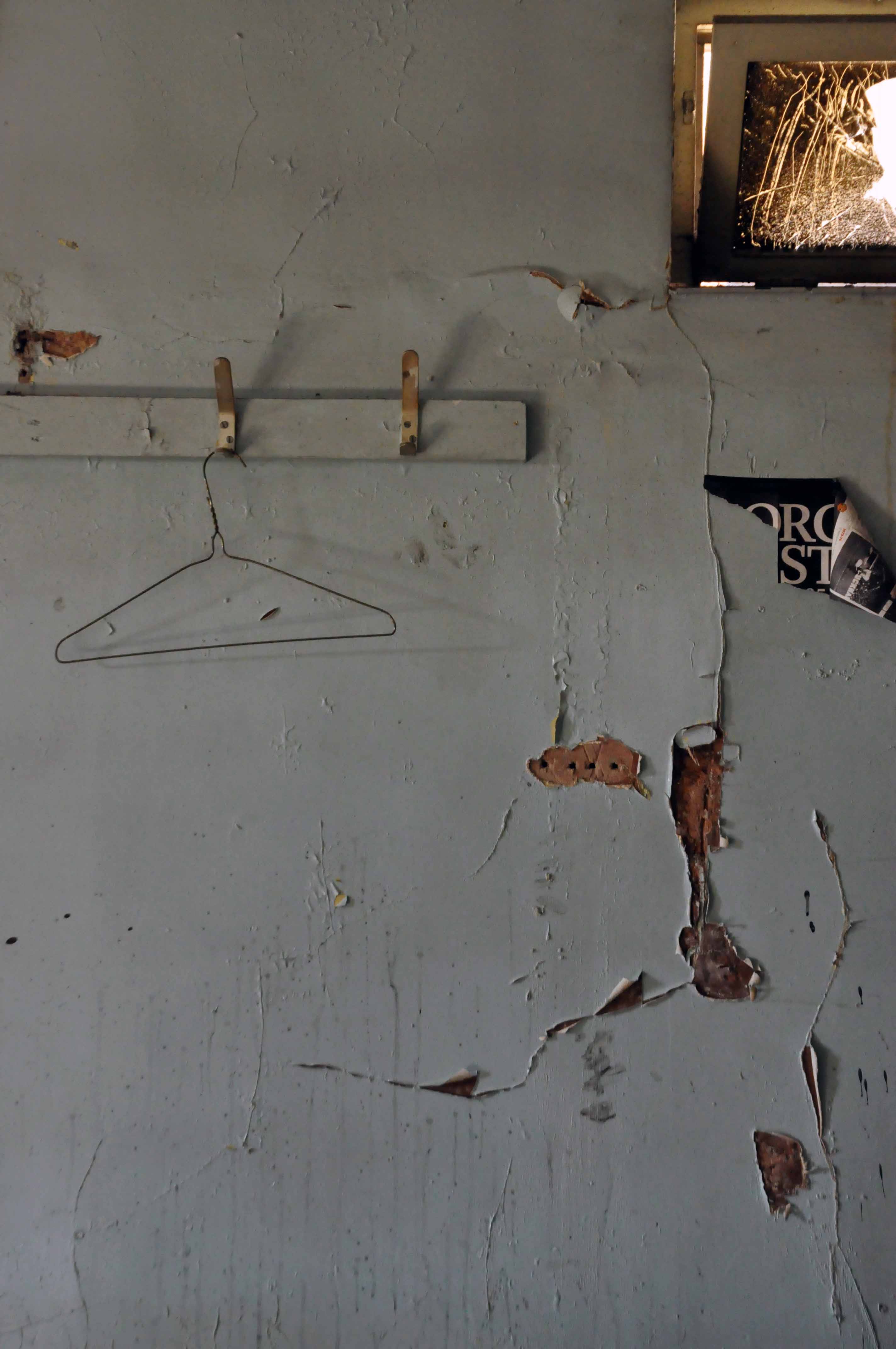

Richmond St Monkwearmouth Sunderland SR5 1BQ

Two swans in front of his eyes

Colored balls in front of his eyes

It’s number one for his Kelly’s eye

Treble-six right over his eye

Edward Thompson, the family printing business, was founded in Sunderland in 1867.

They identified a business opportunity when a local priest, Jeremiah O’Callaghan, ordered some bingo tickets for a parish fund-raising exercise.

From those humble beginnings, Edward Thompson mushroomed in size as Britain went bingo-mad in the 1960s, becoming first the UK’s and then the world’s biggest producer of bingo cards and tickets.

The company which has been printing for more than 155 years – has been hit hard by the crash in bingo hall use as Covid ripped through the leisure sector. CEO Paddy Cronin said he was ‘gutted’ but the business had finally had to face the inevitable as the cashflow dried up.

We were built on a bet but our luck has now run out – he told The Northern Echo.

Covid completely changed the market and as the halls went into decline it just became untenable so I had to break the news to the workers.

They were the pioneers of newspaper bingo, printing the first cards in 1975 and going on to work in places like Bolivia and Belgium and even printing the ballot papers for Nelson Mandela’s 1994 election in South Africa.

So their number is up the factory is tinned-up, house has been called for the very last time.

Yeah, yeah, industrial estate

Well you started here to earn your pay

Clean neck and ears on your first day

Well we tap one another as you walk in the gate

And we’d build a canteen but we haven’t got much space