To begin at the beginning, well actually to begin in the middle and walk to the current beginning. The Gore Brook flows from the Lower Gorton Reservoir and from there onwards to meet the Chorlton Brook in the west, though I should imagine that prior to the construction of the waterworks, it was fed by more distant moorland waters.

Manchester being on the eastern edge of the Lancashire Plain and the western edge of the Pennines is riddled with rivers, rivers which now wriggle in an under and overground web, across heavily developed urban areas. Following the Industrial Revolution former meadow, common and farmland was overwritten by factories, housing and roads, the rural character of the rivers and brooks soon becoming darkened and polluted by the surrounding industries.

I was lead here by my search for a lost pub The Garratt on Pink Bank Lane, then drawn in further by this site The Red Path of Longsight.

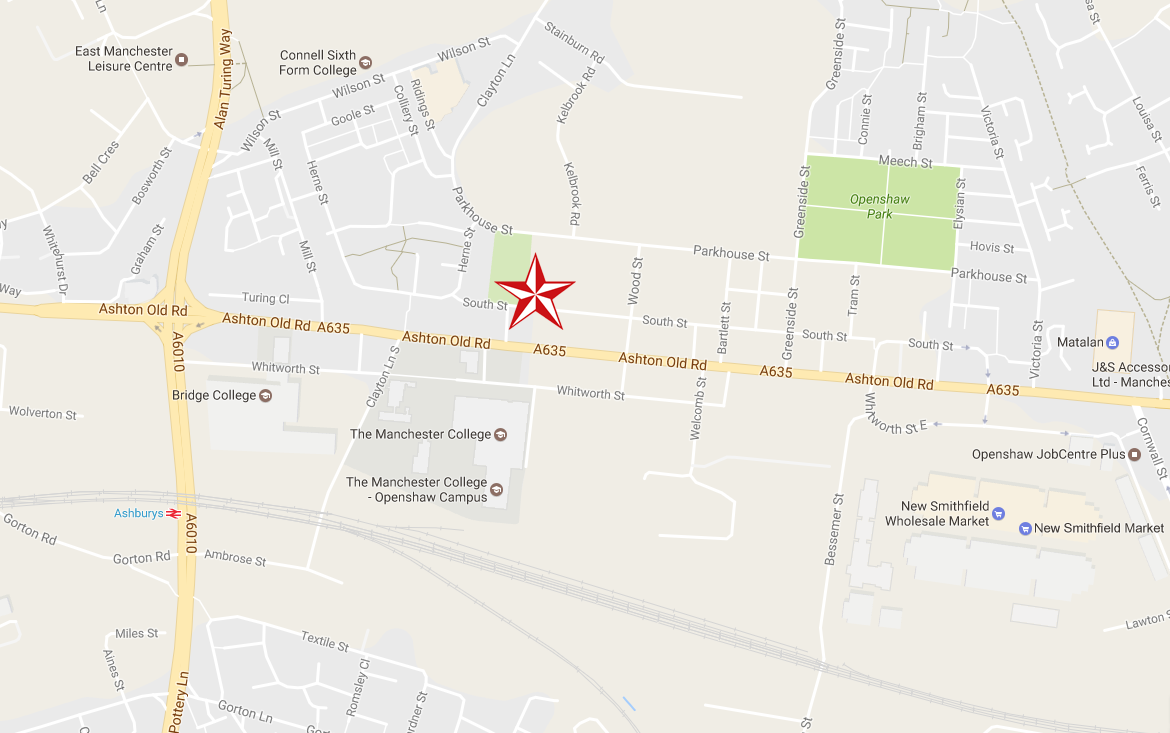

The Red Path is a pedestrian link between Pink Bank Lane and the Gorton boundary at Buckley Road. It roughly follows the course of Gore Brook. The original footpath, running from Buckley Road to the bank of the brook, was made using black cinders. It was probably made in the 1940s to provide access to the allotments located on either side. In the early 1950s , a concrete bridge was laid across Gore Brook and the footpath extended to Pink Bank Lane. This section used red bricks in it’s construction, probably supplied by Jacksons brickworks . Crushed bricks were then used as a topping to make the path smoother and fill in any cracks. The thoroughfare soon became known as the Red Path.

So wide eyed and mapless I bowled up at Brook Terrace, just off Stockport Road Longsight, in search of The Gore and its source.

In the early 1900’s the river was still open and bridged, here at Stockport Road, later culverted and covered – anticipating the arrival of Tesco’s and Granada TV Rentals.

From there we pass under the railway along Brook Terrace and into Parry Road.

The underpass is still there and very much in use, as is Stanley Grove School – the Manchester Central Schools’ Kitchens are long gone, along with the food filled, insulated aluminium cases, that fed the hungry mouths of many, with semolina, pink custard, meat pies and lumpy mash.

Onwards to Elgar Street and still no sign of the river, hidden beneath our feet, the corner of Northmoor Road, can be seen on the corner, no longer distributing dividends, but now providing social housing.

We arrive at Pink Bank Lane, a rich mix of terraced homes, flats and factories – and the long lost Garratt, and the long lost Gore.

Though the lazy, lazy river has been confined in a brick lined wind, to meet the ever pressing needs of the Gorton Sewage Works.

The river then hugs the edge of Annie Lea Playing fields on Buckley Road, until it disappears again as it meets Mount Road, the playing fields are still open ground – the Manchester Cleansing Department, seen on the left – is no more.

Here on Knutsford Road we see the construction of the tunnels and culverts, the footbridge to the left spanning the railway, is still there.

1907

1911

1914

Finally we see The Gore reemerging clear, clean, wide, proud and resplendent in Sunny Brow Park, where it is still maintained as a decorative, duck-filled lake.

1907

1910

1964

Briefly underground again and into the back of Far Lane, skirting the Brookfield Church graveyard.

1920

1937

1964

Then tunnelling under Hyde Road at the back of the church lodge, appearing once again alongside Tan Yard Brow.

1904

1922

1964

The manmade waterfall continues to cascade, the Fairfield to Old Trafford railway is now the Fallowfield Loop, Manchester Cycleway, young lads no longer mess about in wellies and torn Tek Sac jeans on the bank, the Tannery no longer tans.

Then we end our journey by the broad expanse of the Lower Gorton Reservoir, implausibly dotted with jolly yachts, and home to a now absent stepped outflow stream. Look up to the east, and there you’ll see the moors, you could go further.

All archive photographs from Manchester Local Image Collection.