Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014, I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same.

Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014, I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same.

The A5103 is a major thoroughfare running south from Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester city centre to the M56 in Northenden. The road is two-lane dual carriageway with a few grade-separated junctions. It is used by many as a link to the airport and to the motorway network south.

The road starts at Piccadilly Gardens where it meets the A6. It heads along Portland Street – at one time it ran along the parallel Mosley Street, past fast-food outlets and off-licences and then meets the A34 Oxford Street. It multiplexes with that road north for 200 yards into St Peter’s Square and then turns left into Lower Mosley Street, initially alongside the tramlines and then past the former Manchester Central station, now a conference centre with the same name. The road becomes Albion Street and goes over the Bridgewater Canal and under the railway line east of Deansgate station. The road then meets the A57(M) Mancunian Way at a roundabout interchange. This is where most of the traffic joins and leaves.

The road is now 2×2 dual carriageway with the name Princess Road. It passes under the Hulme Arch, a grade-separated junction with the A5067, with an unusually large central reservation. This is presumably because of the proposed plans from the 1960s of a motorway. However, after passing under the junction, there are innumerate sets of traffic lights, with the B5219, the A6010 and the A5145, as well as many other unsigned roads. There are also many speed cameras set at 30 mph.

The road picks up pace as we exit the sprawl of South Manchester and the road becomes Princess Parkway, with a 50 mph speed limit. We cross the River Mersey and almost immediately hit the M60 at J5.

Except for the Manchester City Centre section – which was numbered A5068, this road did not exist on classification in 1922. Princess Road was built in 1932 to serve the new southwestern suburbs; initially it ran between the B5219 and A560 and was numbered B5290, with the road later extended north into the A5068 on the southern edge of the city centre and renumbered A5103.

The northern extension through Hulme initially followed previously existing roads, so followed a zigzag route. As part of the road’s upgrade and the reconstruction of Hulme in the 1970s the road was straightened and the original route can no longer be seen. The A5068 was severed around this time with the construction of the A57(M) and the A5103 took on its city-centre section, taking it to the A6.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road and Rochdale Road and Oldham Road and Ashton New Road and Ashton Old Road and Hyde Road and Stockport Road and Kingsway.

The A57 was nearly a coast to coast route. It passes through three major city centres (Liverpool, Manchester, and Sheffield – with elevated sections in each) and several smaller ones, multiplexes with the A6 and the A1, follows the banks of two canals and negotiates the remotest part of the Peak District. In one city it part of it is a tram route, whilst in another its former route is also a tram route. After all these adventures, it sadly gives up just 40 miles short of the east coast, Lincoln apparently proving too big an obstacle.

The A57 crosses the River Irwell at Regent Bridge before entering its moment of motorway glory as the A57(M) Mancunian Way skirting the south of Manchester’s city centre on an elevated section and crossing the A56 and A34. This includes a half-completed exit that goes the wrong way up Brook Street – a one way street. The original A57 ran further north through the city centre along Liverpool Road (now the A6143) and Whitworth Street – B6469 as far as the A6 London Road which marked the start of a multiplex.

At the end of Mancunian Way, we reach a TOTSO, straight on being the short unsigned A635(M) and thence the A635 – for Saddleworth Moor, Barnsley and Doncaster whilst the A57 turns south, briefly multiplexing with the A6, and then branching off along Hyde Road. This section of road was extensively cleared for the westward extension for the M67, and consequently has seen a lot of redevelopment.

In 2014, having taken early retirement from teaching photography, I embarked on a series of walks along the arterial roads of Manchester.

See also Bury New Road and Cheetham Hill Road and Rochdale Road and Oldham Road and Ashton New Road and Ashton Old Road.

A social history of Wythenshawe and its Civic Centre can be found here at Archives +.

A general history of the garden city’s development can be found here at Municipal Dreams.

Lest we forget, the story begins with a level of overcrowding and human misery that is – thankfully – almost unimaginable in Britain today. In 1935, Manchester’s Medical Officer of Health condemned 30,000 (of a total of 80,000) inner-city homes as unfit for human habitation; 7000 families were living in single rooms.

The estate was always considered to be, in some sense, the realisation of an ambitious vision.

The world of the future – a world where men and women workers shall be decently housed and served, where the health and safety of little children are of paramount importance, and where work and leisure may be enjoyed to the full.

Cooperative Women’s Guild

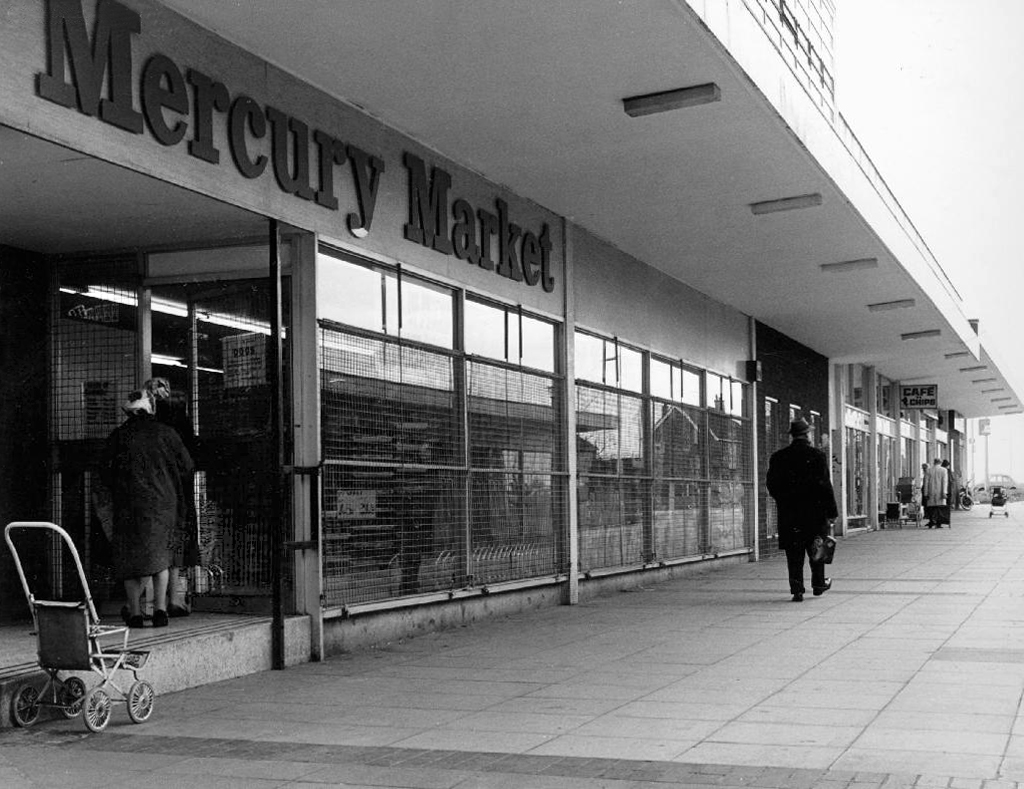

Work began in the interwar years, and continued following the hiatus of 1939-45. The shopping centre named the Civic Centre was open in 1963, the actual Civic Centre containing a swimming pool, theatre, public hall and library in 1971.

A triumph for Municipal Modernism conceived by the City Architects and realised by Direct Works. This post war development owed more to the spirit of Festival of Britain optimism, new construction methods and materials, rather than the grandiose functionalist classicism of the original scheme.

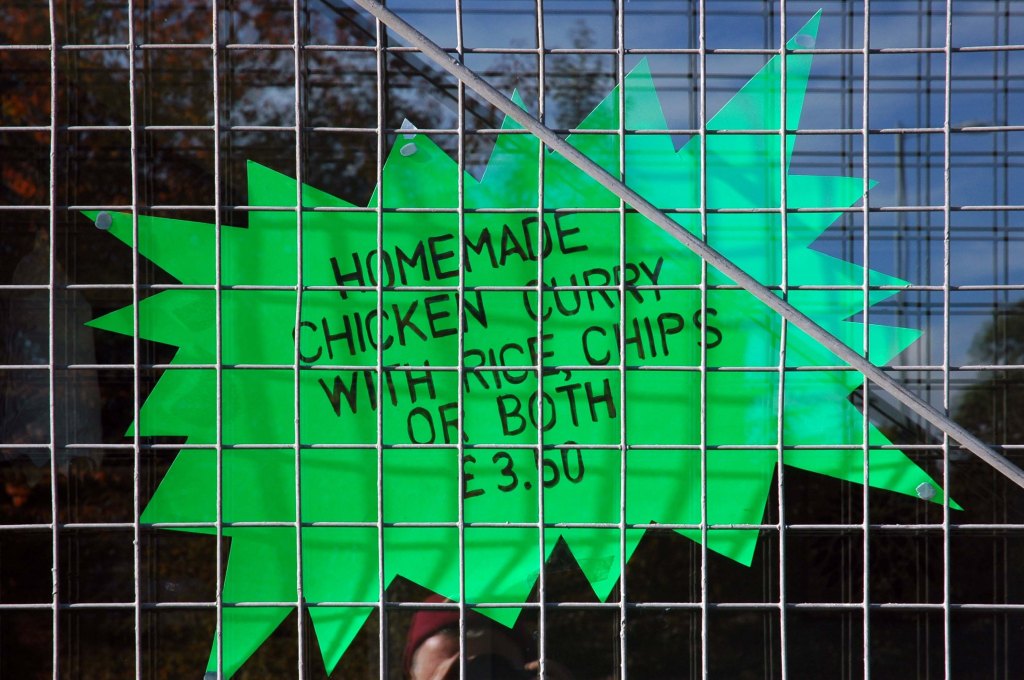

The Co-operative Superstore was a key element in the provision of provisions.

Along with Fine Fare and Mercury Market.

Cantors

Shaw’s

Fred Dawes Whitworth Park Gas Showrooms

New Day furnishing the local HQ was at Hilton House Stockport

The flats were demolished in 2007

Edwards Court and Birch Tree Court 1987 – Tower Block

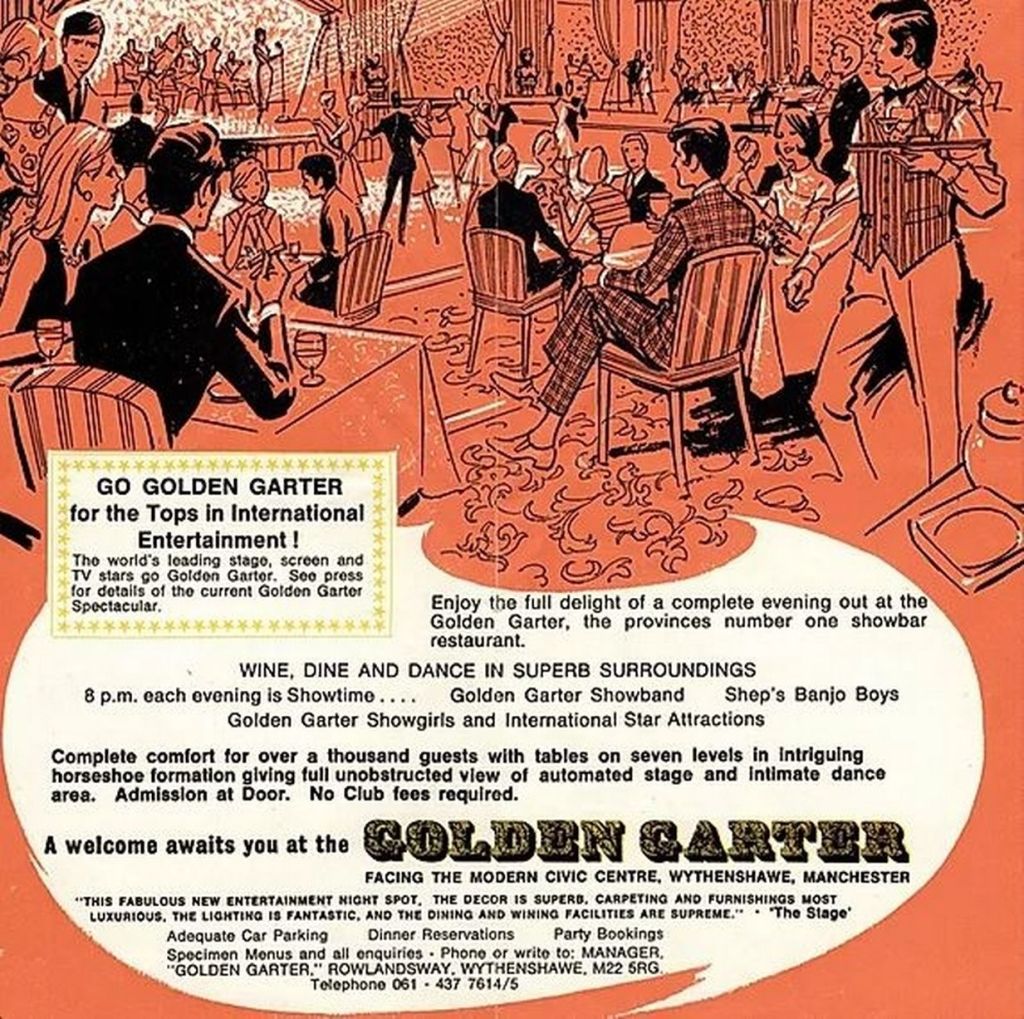

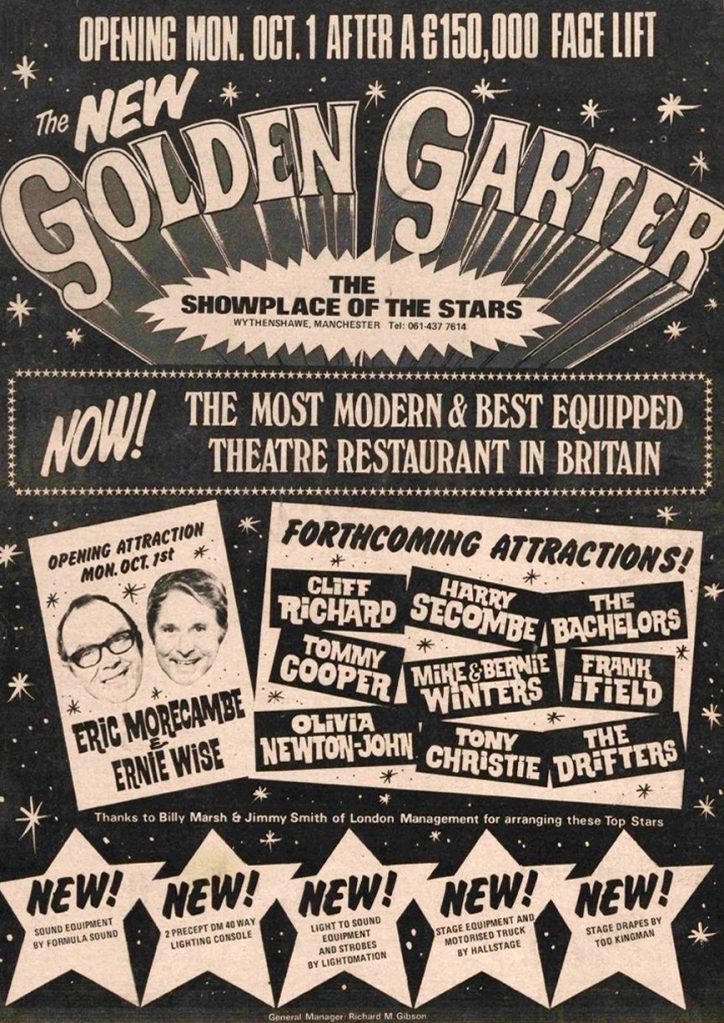

First there was a bowling alley.

Which became the Golden Garter

Closed 3rd January 1983

Then there was a theatre The Forum

There still is – The Forum is a bright and modern hub for co-located services used by community and business.

The original Forum opened in 1971. One of Manchester’s largest public buildings, it had a leisure centre, library, theatre, main hall and meeting rooms. By the mid 1990’s it was under used, had deteriorated internally and externally and needed substantial investment.

The new Forum, along with a new police sub-divisional headquarters and improved transport link was designed to help strengthen the town centre, and provide a landmark project to raise Wythenshawe’s profile within Manchester and beyond.

In the 1980’s they put on a superb array of shows including Roll on 4 O’Clock which starred John Jardine, Jack Smethurst and Glynn Owen. Oh What a lovely War; What the Butler Saw and Habeas Corpus by Alan Bennett. Bury’s own Victoria Wood starred in Talent which she wrote. Another Manchester icon Frank Foo Foo Lammar, famous as the top drag queen of the North-West whose club was re-known for its great party nights appeared in The Rocky horror Show.

A land of elegant covered walkways and raised beds.

A land of 24 hour petrol stations and quadruple Green Shield Stamps.

Some where along the way we lost our way – taxi!

Photographs Manchester Local Image Collection

Second time around – having once cycled the whole way in 2009.

I’ll do anything twice or more – so here we are again, this time on foot.

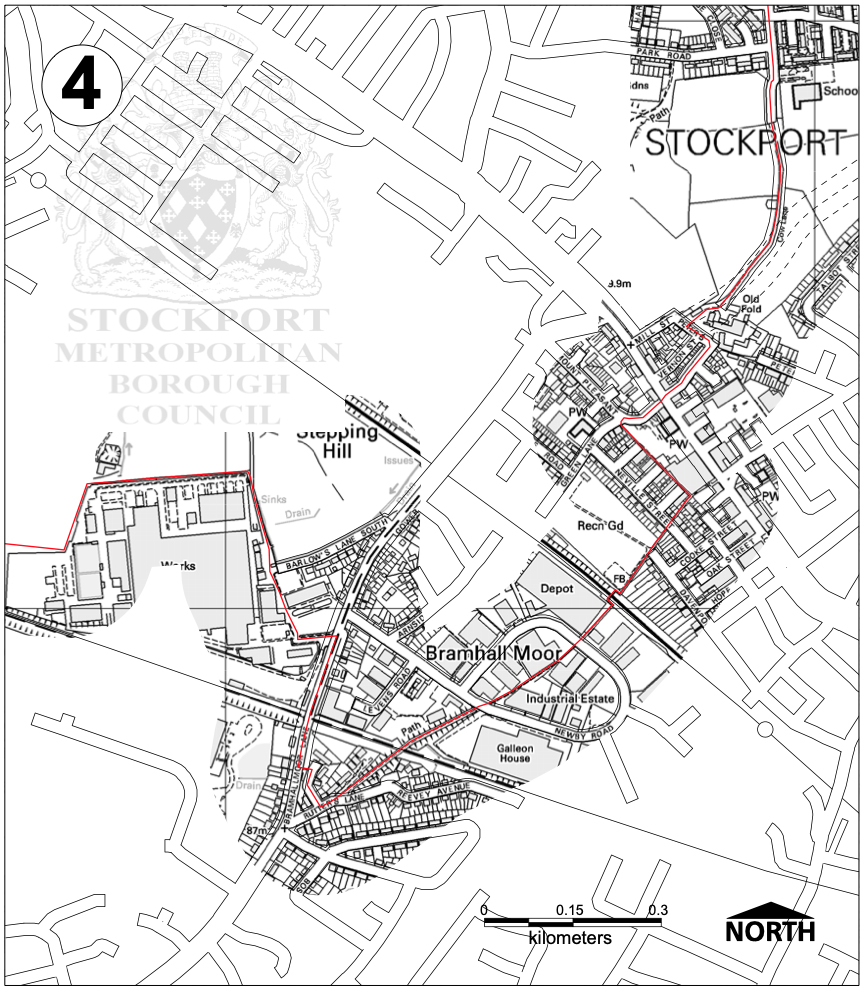

Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start – in the middle, the section from the town centre to Hazel Grove.

Maps are available here for free – we declined the offer, deciding to follow signs instead, many of which were missing or rotated, the better to misinform and redirect – such is life.

We are mostly lost most of the time, whether we like it or know it or not.

We begin at the confluence of the rivers Mersey and Goyt – which no longer seems to be a Way way, the signs having been removed, and proceed down Howard Street, which seems to have become a tip.

The first and last refuge for refuse.

Passing by the kingdom of rust – Patti Smith style.

Passing under the town’s complex internal motorway system by underpass.

Where help is always handily at hand.

Whistling past the graveyard – the site of the former Brunswick Chapel where one and hundred and fifty souls lay lying.

Onward down Carrington Road to Fred’s house.

Through Vernon Park to Woodbank Park – with its heroic erratic.

Almost opposite the entrance to the museum, now set in shrubbery, are the foundations, laid in September 1860, of what was to be a forty metre high Observatory Tower. Despite a series of attempts, funds for the tower could not be raised and the ‘Amalgamated Friendly Societies of Stockport’ eventually had to abandon the idea.

Historic England

Out east and passing alongside the running track.

Lush meadows now occupy the former football field, twixt inter-war semis and the woodland beyond.

Out into the savage streets of Offerton where we find a Buick Skylark, incongruously ensconced in a front garden.

The only too human imperative to laugh in the face of naturalism.

We have crossed over Marple Road and are deep in the suburban jungle of mutually exclusive modified bungalows.

Off now into the wide open spaces of the Offerton Estate – the right to buy refuge of the socially mobile, former social housing owning public.

People living on Offerton Estate have been filmed for a programme entitled ‘Mean Streets’ which aims to highlight anti-social behaviour in local communities.

The next thing we know we’re in a field, a mixed up melange of the urban, suburban and rural, on the fringes of a Sainsbury’s supermarket filling station.

We cross the A6 in Hazel Grove and here for today our journey ends

Ignoring the sign we went in the opposite direction.

As we reach the edge of Mirrlees Fields – the site of the only Fred Perry laurel leaf logo emblazoned way marker.

The Fields are currently designated as a green space and are not available for residential development. But MAN would like to overturn this designation for over one third of the Fields.

MAN Energy Solutions UK is the original equipment manufacturer of Mirrlees Blackstone diesel engines.

Before the Blackstone MAN came in 1842 – the fields were all fields.

To be continued.

Possibly the most famous modern motorway services in the entire land.

Though I’ve never been to see you – I’ve seen your picture reproduced a thousand times or more, particularly your Pennine Tower.

Your even found your way onto a Manchester Modernist’s shirt.

I ride a bicycle, which seriously restricts my access to the world of the M – one and six or otherwise. Having a more than somewhat ambivalent outlook on motor cars and their ways I have nevertheless written a short history.

So to satisfy my idle curiosity, and fill the damp wasteland of a Bank Holiday Sunday afternoon, let’s go on a little trip back in time by means of archival images.

What of your history?

Tendering documents were sent out in 1962 describing it as a 17.7 acre site, requiring at least a £250,000 investment, including an eastern corner reserved for a picnic area, and an emphasis that the views to the west must be considered in the design, and facilities must be provided on both sides. Replies were received – from Telefusion Ltd, J Lyons, Banquets Catering Ltd, Granada and Rank

Top Rank’s plan came consistently highly rated by all the experts it was passed between. It showed a restaurant and a self-service café on the west side, the restaurant being at the top of a 96ft (29m) tower. At the top of the tower was a sun terrace – a roof with glass walls, which they had described but hadn’t included any suggestions for how it could be used, adding that maybe it could form an observation platform, serve teas, or be reserved for an additional storey to the restaurant.

Including a transport café on each site, seating was provided for 700 people, with 101 toilets and 403 parking spaces. A kiosk and toilets were provided in the picnic area.

“The winning design looks first class. Congratulations.”

Architects T P Bennett & Sons had been commissioned to design the services, along with the similar Hilton Park. At £885,000, it was the most expensive service station Rank built, and was considerably more than what had been asked of them. They won the contract, but on a condition imposed by the Landscape Advisory Committee that the height of the tower was reduced to something less striking.

Lancaster was opened in 1965 by Rank under the name ‘Forton’. The petrol station opened early in January, with some additional southbound facilities opening that Spring.

The southbound amenity building had a lowered section with a Quick Snacks machine and the toilets. Above it was the transport café which had only an Autosnacks machine, where staff loaded hot meals into the back and customers paid to release them. These were the motorway network’s first catering vending machines, and the Ministry of Transport were won round by the idea, but Rank weren’t – they removed them due to low demand.

In 1977, Egon Ronay rated the services as appalling. The steak and kidney pie was an insult to one’s taste buds while the apple pie was an absolute disgrace. He said everywhere needed maintenance and a coat of paint, the toilets were smelly and dirty, and the food on display was most unattractive.

A 1978 government review described the services as a soulless fairground.

The Forton Services and the typology generally have had a chequered career, rising and falling in public favour and perception. Purveying food and facilities of varying quality, changing style and vendors with depressing regularity – knowing the value of nothing yet, the Costas of everything.

Ironically the prematurely diminished tower has taken on iconic status in the Modernist canon – listed in 2012 yet closed to the public, admired from afar – in a car.

The Pennine Tower was designed to make the services clearly visible – the ban on advertising had always been an issue, and the previous technique of having a restaurant on a bridge, like down the road at Charnock Richard, was proving expensive and impractical. Rank commissioned architects T P Bennett & Sons to capitalise on the benefits of exciting design while trialling something different. The tower resembles that used by air traffic control, summarising the dreams of the ’60s.

The central shaft consists of two lifts, which were originally a pentagonal design until they were replaced in 2017. They’re still in use to access the first floor, but with the buttons to higher floors disabled. There are then three service lifts, and one spiral staircase – satisfying typical health and safety regulations.

At the top of the tower stood a fine-dining waitress service restaurant, offering views over the road below and across Lancashire. Above the restaurant the lift extended to roof-level, to allow the roof to serve as a sun terrace – although Rank admitted they weren’t sure what this could be used for, suggesting serving tea or eventually building another level.

In reality social changes and cost-cutting limited the desirability of a sit-down meal, and this coupled with high maintenance costs made the tower fall out of favour. The ‘fine dining’ restaurant became the trucking lounge that had been on the first floor, before closing to the public in 1989. It then soldiered on for another 15 years, partially re-fitted, as a head office, then staff training and storage, but even this became too impractical, and the tower is now not used at all.

Although the tower is unique to these services, the concept of large high-level floors can be seen in many Rank services of the era, the idea of each one being to have a visible landmark and a good view of the surrounding area, such as at Hilton Park. The lower-level restaurant at Forton sticks out over the first floor, and partially in to the road, to give an optimum view. Toilets and offices were in the ground floor buildings below.

There are lots of myths flying around that the tower was forced to close by safety regulations, and that it is about to fall down. Like any building which hasn’t been used for 30 years it would take a lot of investment to get it open again, and with roadside restaurants across the country closing due to a lack of trade, nobody has come up with an convincing plan to justify investing in the Pennine Tower.

Many thanks to Motorway Services Online

Take a look at you now.

No more postcards home – y’all come back now, set a spell.