This may be the last time, may be the last time, I don’t know.

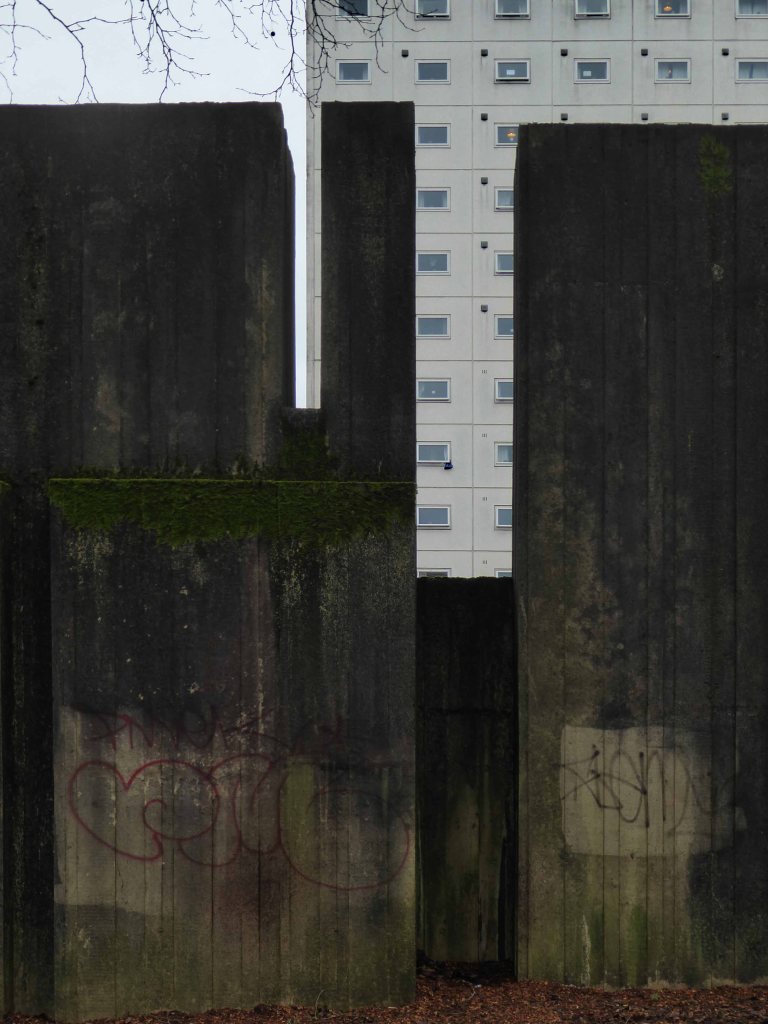

I’ve been taking a look around for several years now, but now the writing is now on the wall.

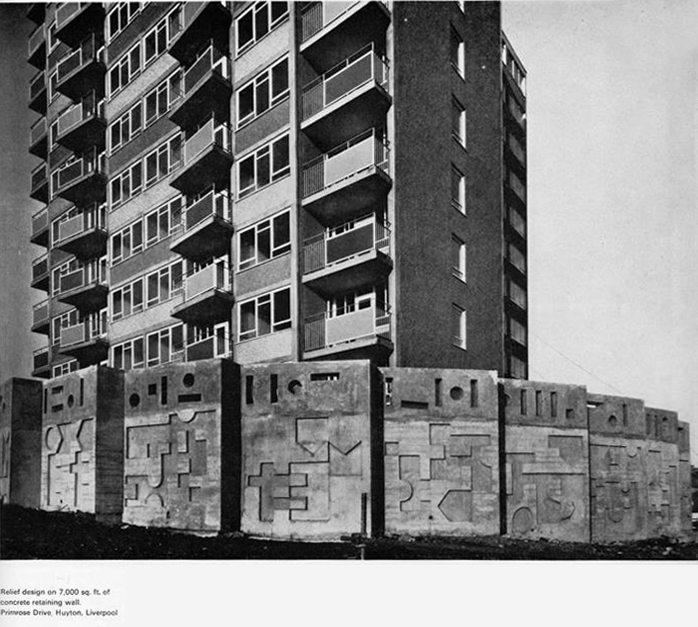

Anthony Holloway’s wall – the only listed structure on the site.

The site is sold, the contractors have arrived, stripping out the buildings earmarked for demolition.

The site is to be contracted – despite all efforts to have its integrity preserved.

The Pariser Building is to be retained.

Along with the Renold Building – which is already home to start up tech businesses.

The city council has approved Bruntwood SciTech’s change of use bid to transform the 110,000 sq ft Renold building into a tech and science hub.

In a joint venture with the University of Manchester, Bruntwood will create 42,000 sq ft coworking and business incubator spaces for businesses in the sector at the Altrincham Street building.

Sister is Manchester’s new innovation district. A £1.7bn investment into the city, its setting – the former University of Manchester North Campus and UMIST site – is steeped in science and engineering history. Home to the UK’s most exciting new ideas and disruptive technologies, Sister is a worldclass innovation platform in the heart of one of the most exciting global cities. It stands as the city’s symbol of a new era of discovery that promises progress against humanity’s greatest challenges.

So it is with a bitter sweet feeling that I took a group of Modernist Moochers around the site this Saturday – a number of whom had been students there.

As a former UMIST student 1990-1997, I had a wander round the old site recently, sad to see it so empty and run-down.

So let’s take a look at the current state of affairs.