Second time around, following my post in 2019.

A terminal halt on the Campus Capers walk.

Taking a walk around town on an overcast and intermittently showery Friday, we’re all here again.

Sat at home on an overcast and intermittently showery Monday, I took a walk around online archives.

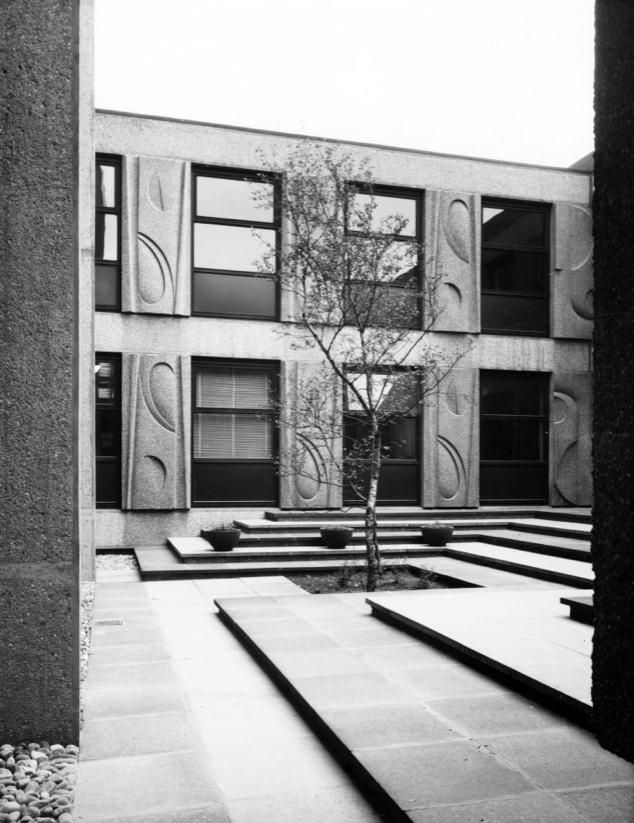

1962 to 1963 Photos: Local Image Archive

The inner courtyard was originally paved, subsequently grassed over.

The lack of sunlight has resulted in the grass becoming both waterlogged and moss-bound.

As a former TMBC maintenance gardener I recommend raking out, aeration and a top dressing of light river sand as a remedy.

Ribapix 1964

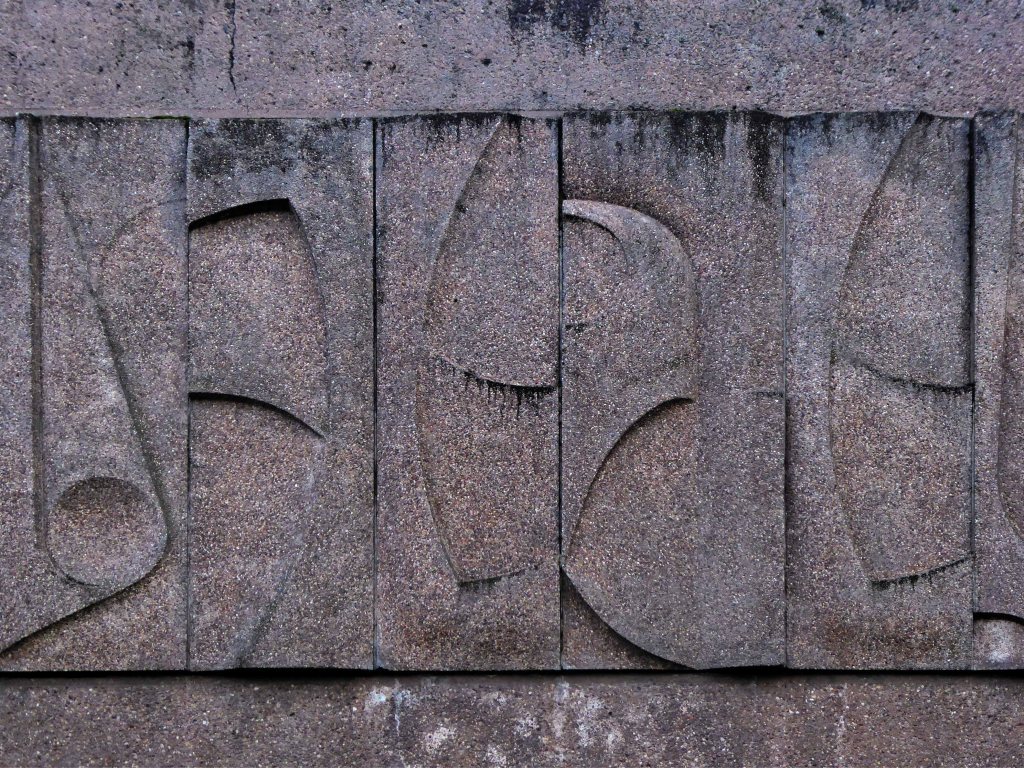

The William Mitchell concrete panels are of a modular design, rotated to form distinct groups of horizontal and vertical rhythms. A number of the buildings elevations are clad in linear, diagonal and vertical forms, though the majority are curvilinear and organic.

Local Image Collection 1972

The Ellen Wilkinson building, home to Education and Communication, is one of the few buildings on campus named after a woman. She gained the nickname of ‘Red Ellen’ in her political career, due to her socialist politics and vibrant red hair colour.

Wilkinson was a successful Labour party politician and feminist activist, and a passionate and bold personality in the Houses of Parliament. She was made Minister of Education under Clement Atlee’s government, making her the second woman to ever get a role in the British cabinet. She was brought up and educated in Manchester, making her legacy on the Manchester campus even more significant.

Ellen Wilkinson is a large sized building with three blocks. There are six floors in C Block, five floors in B Block and seven floors in A Block.

There are three lifts and six main staircases within the building.

The floors are signed as Ground, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. This is slightly different inside the lifts where control buttons are marked as 0 instead of Ground.

There are link passages from A and B Block to C Block on levels Ground, 1 and 3.

The building was the work of George Grenville ‘GG’ Baines and Building Design Partnership.

This scheme pre-dates Wilson Womersley’s appointment as masterplanners for the Education Precinct but exists harmoniously with the later series of buildings. This is most likely due to the method of development before any ‘grand concept’. The incremental expansion of the University, following WWII, was largely dictated by the progress of compulsory purchase orders; this group was no exception. At the planning stages, the lack of a masterplan led to organising the wings of the buildings in an open, orthogonal arrangement. This would allow expansion in a number of directions, according to the next available site in ‘the dynamic situation’. The result was the creation of a small courtyard flanked by two five-storey blocks and a two-storey structure. All three buildings use the same pink-grey concrete. The plastic qualities of concrete were explored in both cladding and structural panels and the textural qualities exposed in the bush hammered columns, to reveal the Derbyshire gravel aggregate. The sculpted and moulded panels on the two-storey block and on the gable ends of the larger blocks were designed in collaboration with William Mitchell. The only other materials in the external envelope were the windows of variously clear and tinted glass. The window modules were set out against a basic geometry in three standard patterns and applied across the façade. This resulted in a clever interplay of vertical and horizontal expression. Phase II, a seven-storey teaching block, was not as refined in its details.

if you have a moment to spare, why not ascend and descend the spiral stairway.

The seating area is almost intact.

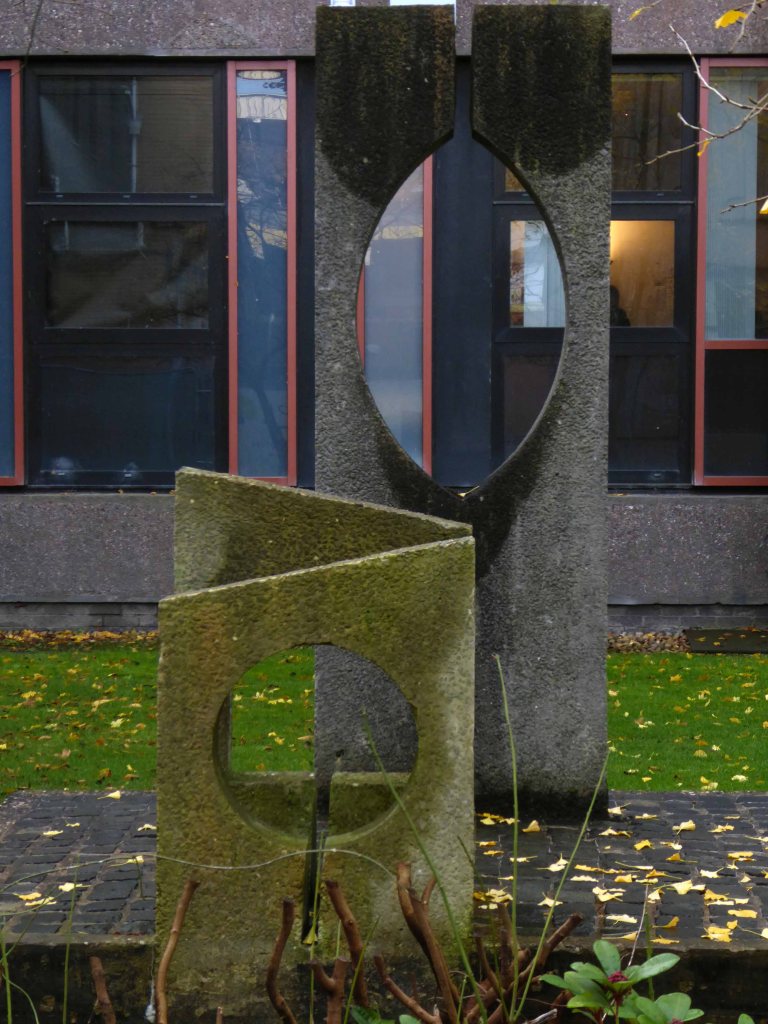

This trio of abstract concrete forms, a B&Q Barbara Hepworth, has defied attribution, I adore it.

Similar curved panels have also been used at The Bower – Old Street London.