Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014 I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same on Ashton New Road.

Having photographed the arterial roads of Manchester in 2014 I have resolved to return to the task in 2024.

Some things seem to have changed, some things seem to have stayed the same on Ashton New Road.

The history of youth work goes back to the birth of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, which was the first time that young men left their own homes and cottage–industries to migrate to the big towns. The result of this migration was an emergent youth culture in urban areas, which was responded to by the efforts of local people.

Work with young women however was seen as less important, because young women’s needs at this time were seen as being centred on homemaking, which were already, supposedly, provided for in the home.

By 1959 widespread moral panic in the press about teenage delinquency led the British government to look into a national response to catering for the needs of young people. In 1960 a government report known as The Albemarle Report was released, which outlined the need for local government agencies to take on responsibility for providing extracurricular activities for young people. Out of this the statutory sector of the youth service was born. For the first time youth centres and fully paid full-time youth workers made an appearance across the whole of Britain.

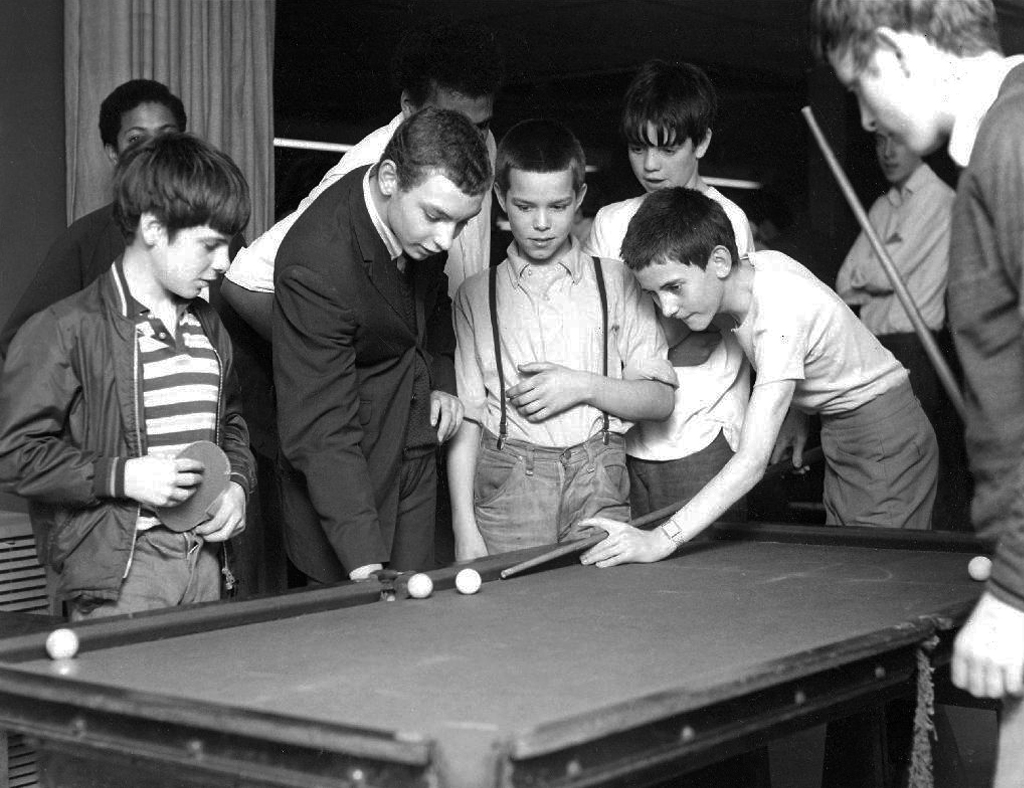

Which is where I enter this short history, attending the Broadoak Youth Club in Ashton, during the late 60s early 70s. These were days of ping pong, snooker, spinning 45s and drinking pop if you had the coppers.

Council run, housed in an architectural style best described as bunker like.

I uncovered a little of Manchester’s youth club history during my travels.

The Ardwick Lads’ and Mens’ Club on Palmerston Street, latterly the Ardwick Youth Centre, opened in 1897 and is believed to be Britain’s oldest purpose-built youth club still in use and was until earlier in 2012. Designed by architects W & G Higginbottom, the club, when opened, featured a large gymnasium with viewing gallery – where the 1933 All England Amateur Gymnastics Championships were held – three fives courts, a billiard room and two skittle alleys – later converted to shooting galleries. Boxing, cycling, cricket, swimming and badminton were also organised. At its peak between the two world wars, Ardwick was the Manchester area’s largest club, with 2,000 members.

On the 10th September 2012 an application for prior notification of proposed demolition was submitted on behalf of Manchester City Council to Manchester Planning, for the demolition of Ardwick Lads’ Club of 100 Palmerston Street , citing that there was “no use” for the building in respect to its historic place within the community as providing a refuge and sporting provision to the young of Ancoats.

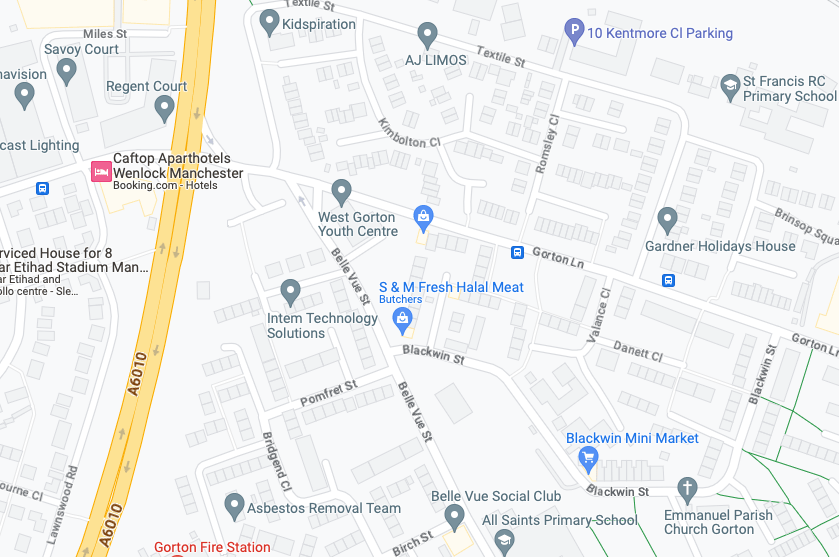

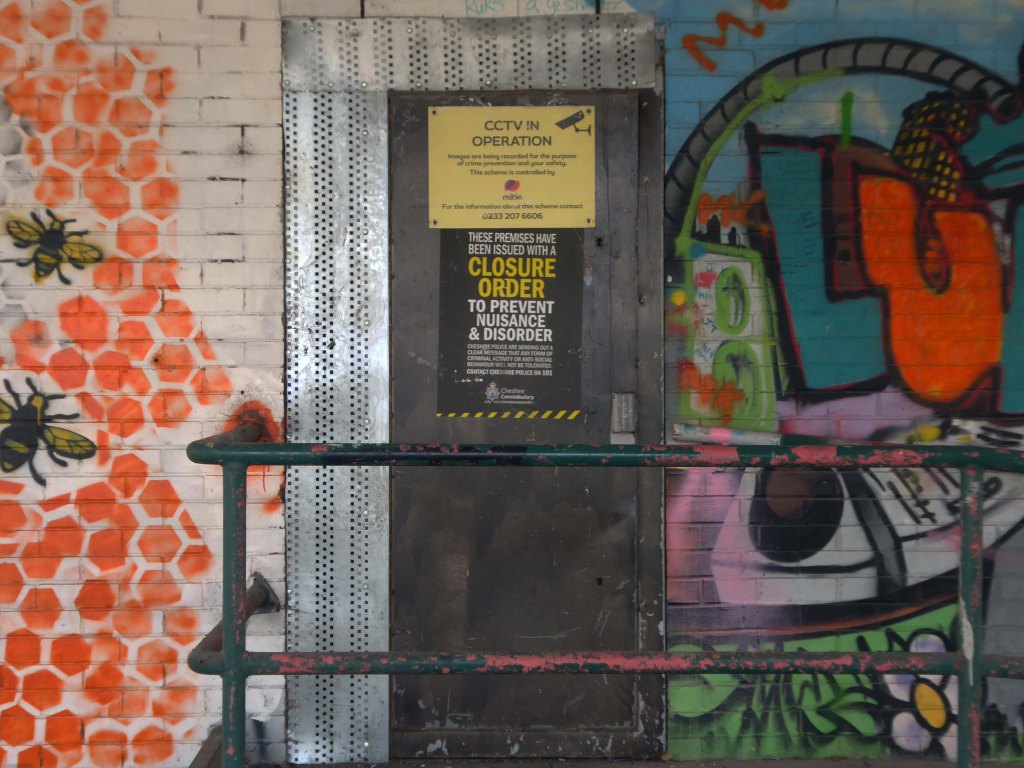

Whilst cycling through Gorton, I passed the now defunct West Gorton Youth Centre.

Intrigued I started to dig a little deeper, I remembered playing five-a-side at Crossley House in Openshaw.

Openshaw Lad’s Club was founded in November 1888 by William John Crossley. It was previously known as the Gorton and Openshaw Working Lad’s Club and the Crossley Lad’s Club. The Crossley family financed the club up to 1941 and they built the club premises, Crossley House to commemorate Sir William Crossley after his death in 1911. The building was opened on 1 September 1913. In July 1941 the premises were handed over to the National Association of Boy’s Clubs and a management committee was formed to administer the club

Simon Inglis gives the architect as John Broadbent; Buildings of England names the architect as James Barritt Broadbent.

Architects of Greater Manchester

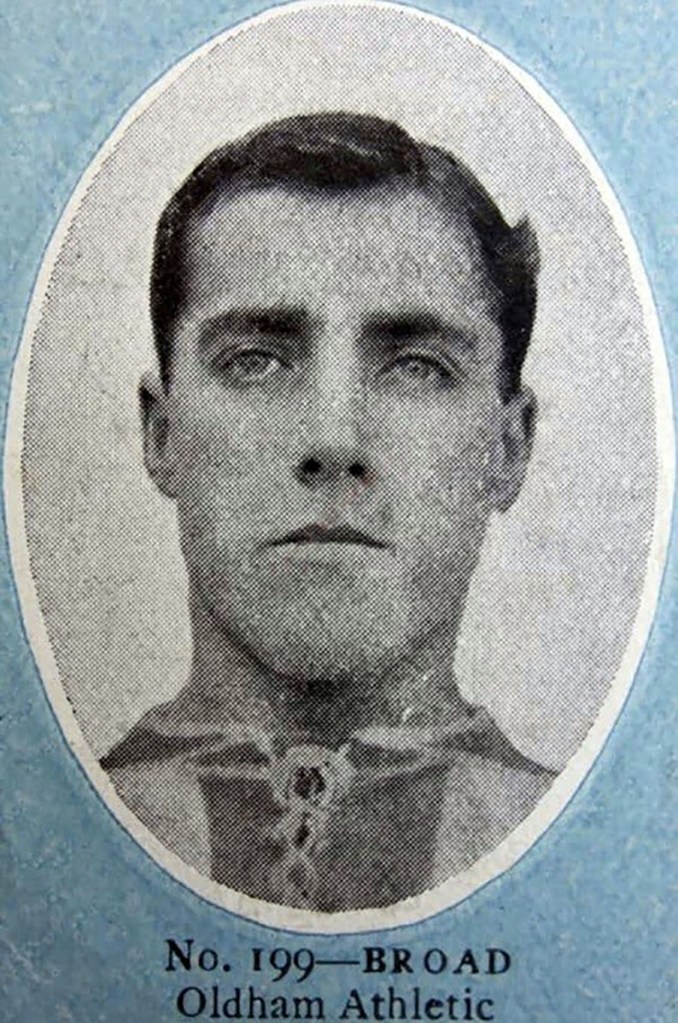

Stalybridge born outside right Tommy Broad started with Redgate Albion in 1902 spending time at Manchester City without making their first eleven before playing for Denton Wanderers in 1903 and Openshaw Lads Club in 1904 from where he joined Second Division West Bromwich Albion in September 1905 making his Football League debut at Wolverhampton Wanderers that September. After a single goal in 15 appearances he moved to Chesterfield Town in the February 1908 scoring 5 goals in 50 appearances for The Spireites over the next two seasons at Saltergate, where he was an ever present in 1908-09.

He moved to Second Division Oldham Athletic in May 1909 and they were promoted as Second Division runners-up in his first season when he missed only one game, scoring a career best 7 goals in the campaign, and in three seasons at Boundary Park he scored 9 goals in 104 appearances. He then played for Bristol City between the summer of 1912 and the suspension of peacetime football due to the onset of the First World War in 1915, where he missed only one match in his first two seasons, scoring 8 times in 111 appearances at Ashton Gate.

During the First World War he served in the Armed Forces and after its resolution he joined First Division Manchester City in the summer of 1919, making 44 appearances in two years at Hyde Road, and helping The Citizens to finish runners up in the League Championship in 1920-21, which he followed with a move to Stoke in the summer of 1921 where Broad along with his younger brother Jimmy helped The Potters to promotion in 1921-22, finishing as Second Division runners-up, although this was followed by relegation the following season.

After three years in The Potteries, where Broad scored 4 times in 89 first team appearances, he moved to the South Coast to join Southampton. Broad still holds the distinction of being the oldest player ever signed by The Saints, being just three weeks short of his 37th birthday. At The Dell, he was used as cover for Bill Henderson and only had a run of three games in October, followed by six more appearances in April. In September 1925, Broad moved to Weymouth of the Western League, before playing out his career with Rhyl.

Manchester City’s ground was up the way at Hyde Road Stadium at the time.

In 2013 disaster struck the club:

A legendary boxing gym – former base of superstars Ricky Hatton and Marco Antonio Barrera – could be forced to shut after it was ransacked by thieves.

Crooks ripped out copper piping and stole priceless equipment from the Shannon Boxing Club in Openshaw.

Searching the Local Image Collection – revealed other locations.

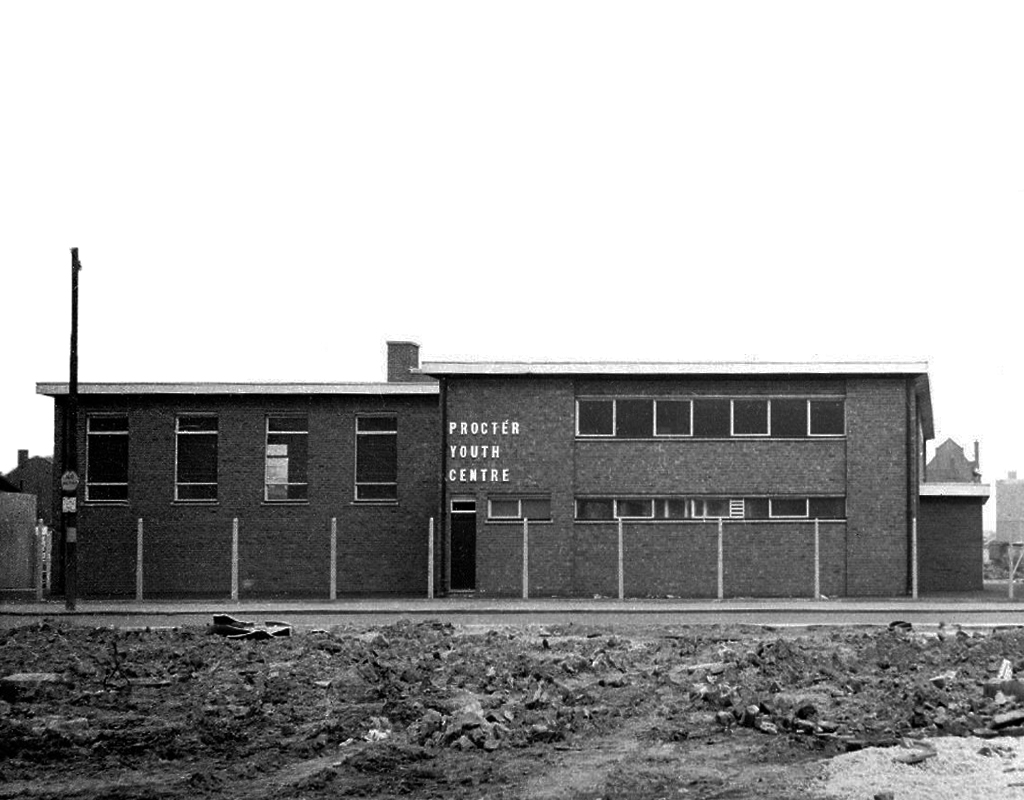

Procter Youth Centre a victim of city’s spending cuts

Procter Youth Centre 1966-2011. Despite being in singularly ugly building, it was very popular, providing a wide range of activities such as pool, football and martial arts, to name but a few. In 2009 the premises were refurbished with £668,000 being spent on a weights room, dance studio, recording studio. Then two years later Manchester City Council did the logical thing – closed it! Some of the eight staff offered to take a pay cut but to no avail. There were plans to use the building as a pupil referral unit. Today the building stands in the middle of wasteland that is the process of redevelopment.

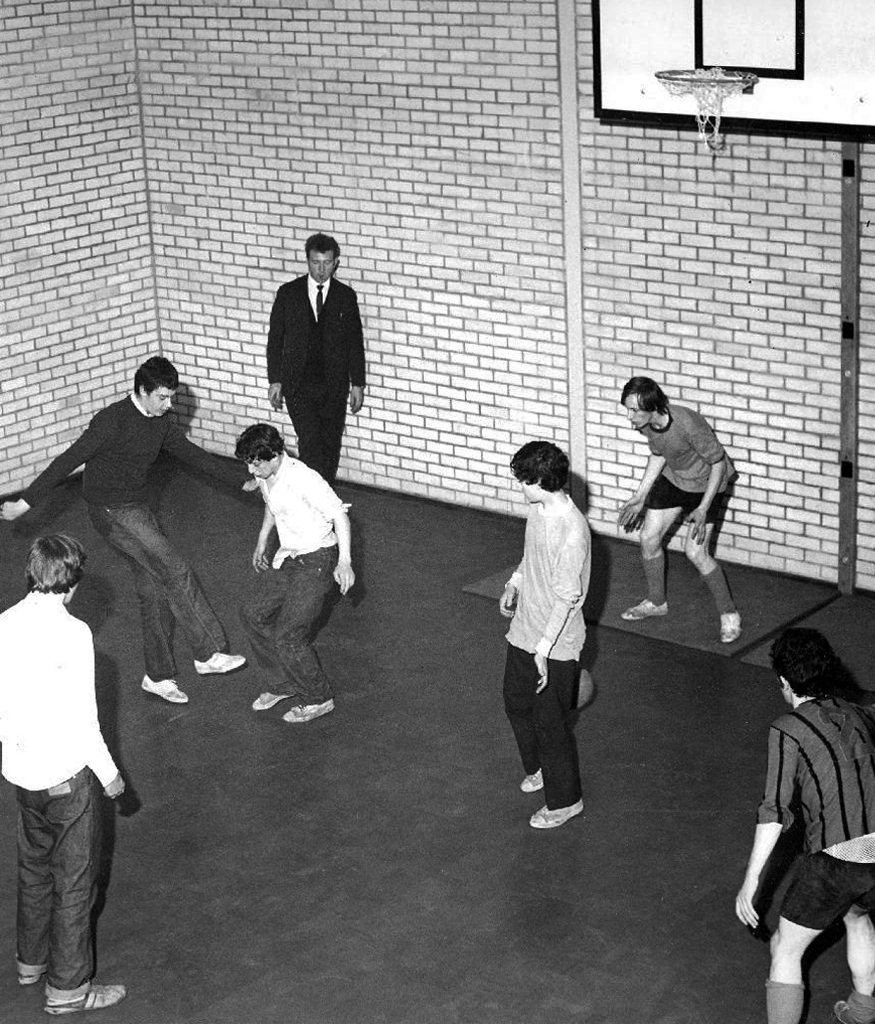

Hulme 1972

Ancoats 1962

Ancoats Youth Club had sadly ceased being a place for the community to come together and use the facilities a number of years before it became a bed shop before it was finally demolished in 2011, with yet another community resource gone forever.

Ancoats

Moss Side 1972

Blackley 1969

Victoria Park St Edwards Youth Club 1976

Fielden Park 1972

Newall Green 1972

Royal Oak Community Centre Baguley

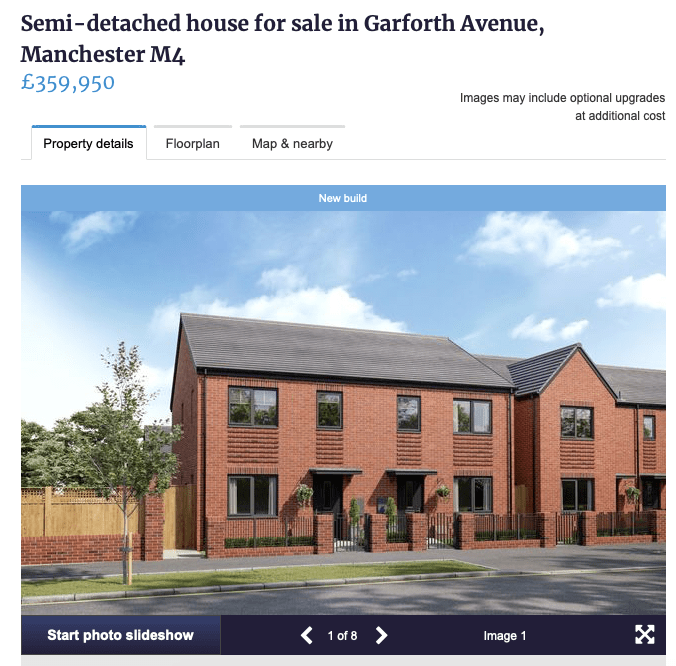

Bringing us back to Gorton – the unoccupied and demolition ready Youth Centre.

Surrounded by new-build and no stranger to a passing Bentley.

Where the state has created a vacuum the charitable sector steps in.

Designed by Seven Architecture, the Manchester Youth Zone East will be the second of its type in Greater Manchester, following the Factory Youth Zone in Harpurhey.

HideOut Youth Zone is a registered charity based in Manchester and has been in existence since 2019.

We are a Youth Zone dedicated to providing opportunities and experiences to all local young people.

Following years of slow decline the area is on the up.

Linden Homes’ new build properties on Belle Vue Street, Gorton have now completely sold out, with the first of the 14 homes ready for homeowners to move into this month.

The properties are part of the £9m Grace Gardens development, which is situated in a prime location in an up-and-coming part of Greater Manchester.

Though affordability is always an issue.

Manchester now runs three Youth Centres across the city.

This is my first visit to a match day at the Etihad – having last watched City at Maine Road, from that uncovered corner enclave, the Kippax Paddock – the so called Gene Kelly Stand

Singing in the Rain

It all ended in ruins.

Demolished, the last ball kicked in anger Sunday 11th May 2003.

To the other side of the city and rebranded Eastlands, occupying the former Commonwealth Games Stadium.

Owners John Wardle and Thaksin Shinawatra came and went.

Since 4 August 2008, the club has been owned by Sheikh Mansour, one of football’s wealthiest owners, with an estimated individual net worth of at least £17 billion and a family fortune of at least $1 trillion.

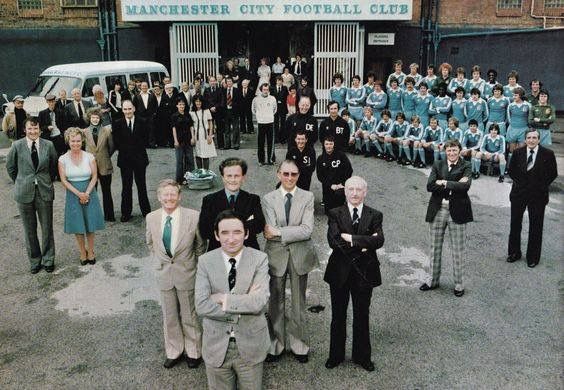

A far cry from Peter Swales and his TV Repair shop on Washway Road.

The game has changed, money is in motion, fans travel from every corner of the globe, fuelled by the Murdoch Dollar and the insatiable thirst for televised football.

So it’s the 22nd September 2013 – I though I’d take a look around town first.

Kits and colours in abundance – though some of these colours can and will run.

Off then to the Etihad and its the Pellegrini squad versus Moyes’ boys.

This is a world within a world as the Middle East seeks to lighten its carbon footprint, and put its size nines all over east Manchester.

Corporate greeting on Joe Mercer Way, executive sweeteners, in the form of earthbound airline hostesses.

Groups from the Antipodes happy to embrace the jumbo blue letters – no boots, no hustling, no barging through swelling crowds, no menacing looks from beneath feather cut fringes.

No none of that any more.

I made my excuses and left.

Manchester City ensured David Moyes’ first derby as Manchester United manager ended in abject humiliation with a crushing victory at the Etihad Stadium.

In contrast to the despair of his opposite number, it was a day of delight for new City boss Manuel Pellegrini as he watched the rampant Blues make a powerful statement about their Premier League ambitions.

Sergio Aguero and Yaya Toure gave City a commanding half-time lead and any slim hopes of a United recovery were snuffed out by further goals from Aguero and Samir Nasri within five minutes of the restart.

Charles Dreyfus was a French emigrant chemist and entrepreneur, who founded the Clayton Aniline Company on 29 May 1876. The company obtained a lease on a parcel of land in Clayton, Manchester, sandwiched between the Manchester and Ashton Canal and Chatham Street – later known as Clipstone Street.

At its peak in the 1970s, the site occupied over 57 acres and employed over 2,000 people. However, due to the gradual demise of the British textile industry, most textile production shifted to countries such as China and India with the textile dye industry following.

In 2002, the company made 70 members of staff redundant and in 2004 the announcement was made that the site would be closing with the loss of over 300 jobs. A small number of staff were retained to assist in the decommissioning of the plant. The last workers left the site in 2007 and the remainder of the buildings were demolished shortly afterwards.

Like much of the industry of east Manchester its tenure was relatively short – money was made and the owners departed, without wiping their dirty feet.

The site remained derelict until demolition, followed by extensive site cleansing – to remove the dangerous detritus of 200 years of hazardous chemical production.

It is now occupied by the Manchester City FC training academy.

Vincent Kompany had just completed his £6million move from Hamburg when he realised that Mark Hughes’ sales pitch about the direction the club was going was not entirely accurate.

They took me for a look around the training ground at Carrington – it wasn’t fit for purpose, it was a dump.

I remember there was a punch bag in the gym – and only one boxing glove. And even that had a big split in it!

Then in 2008 the corrupt boss Thai PM Thaksin Shinawatra is bought out by Sheik Mansour – the rest is history/mystery.

Mr Peter Swales makes no comment.

My interest lies in the company’s Ashton New Road offices – seen here in 1960.

Demolished and replaced by a distinctly Modernist block by 1964.

A flank was added on Bank Street along with a bank.

Archive photographs Manchester Local Image Collection

The office complex is still standing, now home to Manchester Police, I risked arrest and incarceration, in order to record the distinctive tile work, rectilinear grid and concrete facades.

Attracting several suspicious stares from the open glazed stairwells.

Let’s take a look.

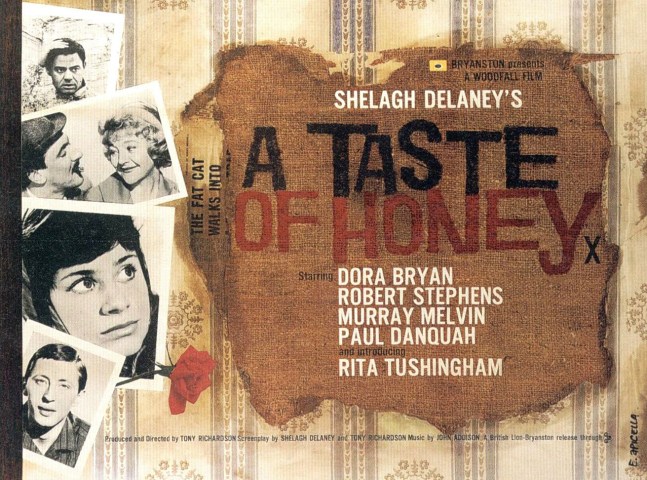

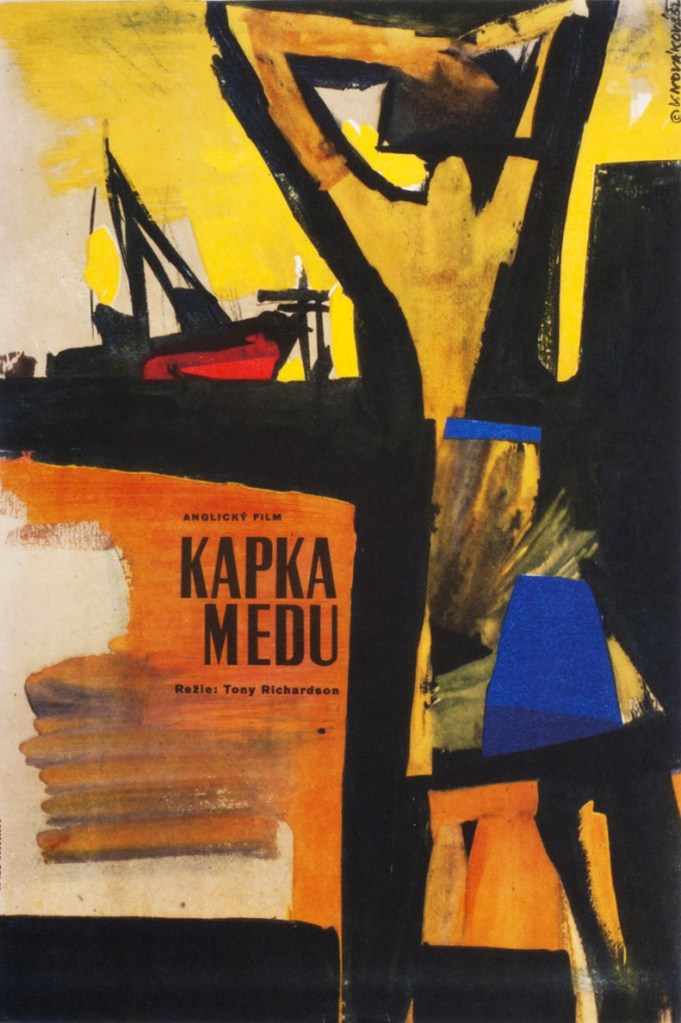

This is a film that has stayed with me for most of my life – first seen as a nipper, fascinated by the fact that it was shot in a very familiar landscape.

As years have passed I have watched and rewatched it, finally resolving to track down the local locations used in its filming.

Studying and pausing the DVD, making thumbnail sketches of frames, researching online – referring to Reelstreets.

I have previously written about the way in which the movie shaped a particular image of the North.

And examined particular areas of Manchester such as Barmouth Street.

The film generated world wide attention and remains just as popular today.

Still watched, still loved, still relevant – here are a selection of photographs I took in 2011 – cycling around Manchester, Salford and just a little closer to home in Stockport.

Larkhill Road scene of the moonlight flit

The descent from Larkhill Road

Stockport Viaduct

Stockport Parish Church

Stockport running for the bus to Castleton

Midway Longsight – where Dora Bryan sang

Barmouth Street were the school scenes were filmed.

Timpson’s shoe shop now demolished opposite the Etihad

Phillips Park the back of the gas works in Holt Town

The Devil’s Steps Holt Town

Rochdale Canal

Ashton Canal

All Souls Church Every Street Ancoats

Piccadilly Gardens as we view the city from a moving bus.

Manchester Art gallery – where they watched the Whit Walks.

Albert Square part of the earlier bus ride.

Trafford Swing Bridge

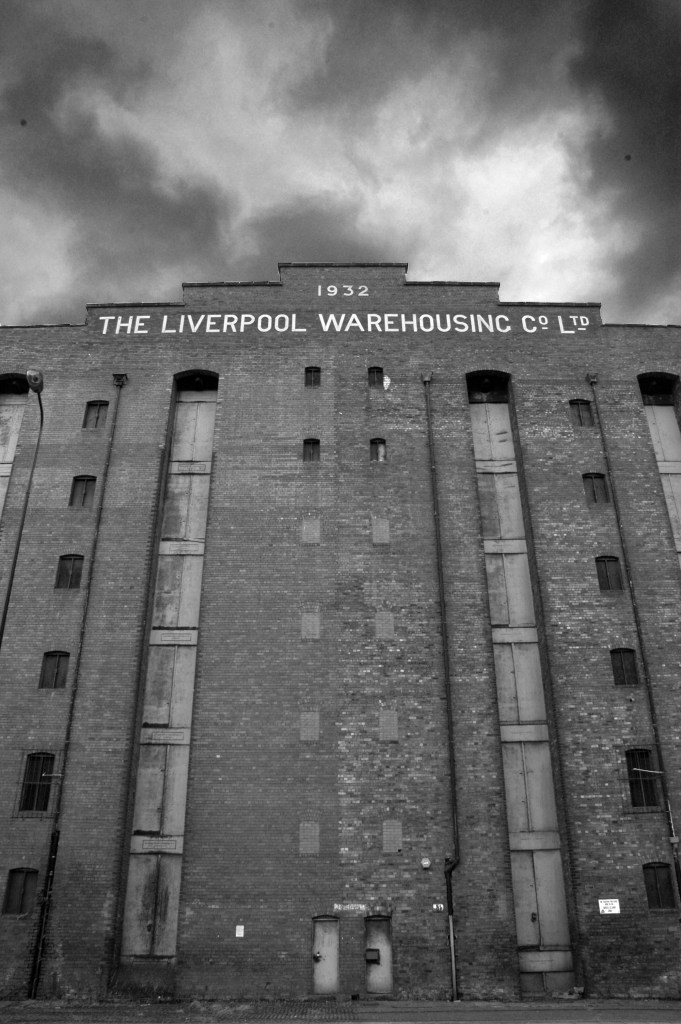

Dock Offices

Chimney Pot Park Salford

Pendleton

Barton Aqueduct

Through my tour I have attempted to capture a sense of the settings as they are – how, if at all, the areas have changed.

There may be some minor inaccuracies or omissions which I am happy to amend.

You may wish to visit the sites yourselves, the majority of which are easily accessible, above all watch the film and appreciate that which is around you.

Portrait of Shelagh Delaney – Arnold Newman

Standing stately on the corner of Carruthers and Pollard Street, safe as houses.

As safe as the houses that are no longer there, along with the other public houses, along with the jobs, along with the punters – all long gone, it’s a long story.

Look out!

Mind that tram, full of the boys and girls in blue, off to shriek at a Sheikh’s shrine.

The Bank of England was one of Ancoats’ first beerhouses, licensed from 1830 and ten years later it was fully licensed with attached brewhouse. The brewery did well, in fact it had another tied house, the Kings Arms near Miles Platting station nearby. The brewery was sold off in the 1860s but continued as a separate business for a few years.

Ancoats, the core of the first industrial city, a dense cornucopia of homes, mills and cholera – its citizens said to find respite from disease, through the consumption of locally brewed beer.

Once home to a plethora of pubs, now something of a dull desert for the thirsty worker, though workers, thirsty or otherwise are something of a rarity in the area.

One worker went missing, some twenty years ago Martin Joyce was last seen on the site, the pub grounds were excavated – nothing was found.

When last open it was far from loved and found little favour amongst the fickle footy fans.

To the north a tidal wave of merchant bankers, to the east redundant industry.

The Bank of England has gone west.

So clean the mills and factories

And give me council houses too

And work that isn’t turning tricks

Like building homes and making bricks.