Why are we here?

The Halifax was formed in 1853 as the Halifax Permanent Benefit Building and Investment Society. The idea was thought up in a meeting room situated above the Old Cock Inn close to the original Building Society building. Like all early building societies, the purpose of the society was for the mutual benefit of local working people.

Why are we not here?

In 2006, the HBOS Group Reorganisation Act 2006 was passed. The aim of the Act was to simplify the corporate structure of HBOS. The Act was fully implemented on 17 September 2007 and the assets and liabilities of Halifax plc transferred to Bank of Scotland plc. The Halifax brand name was to be retained as a trading name, but it no longer exists as a legal entity.

What have we here?

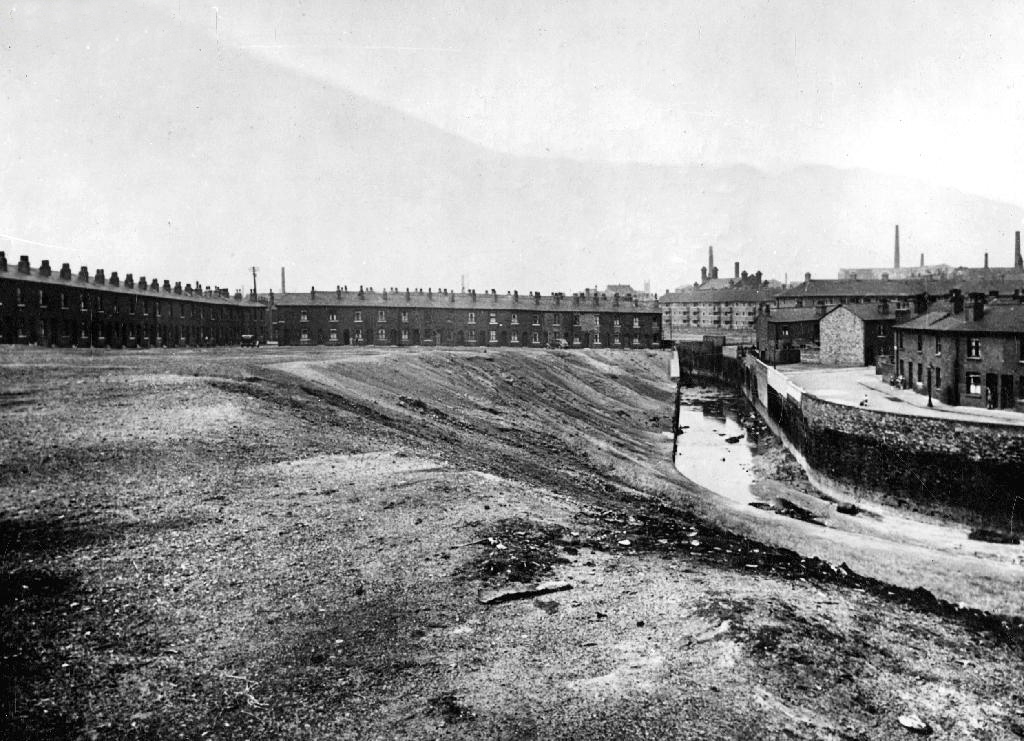

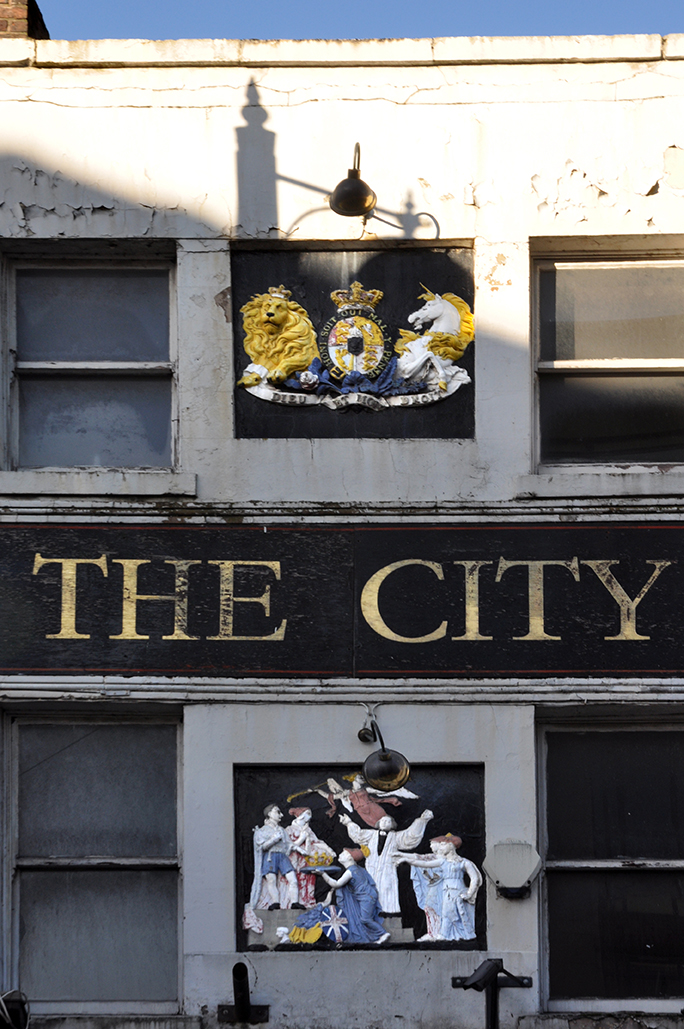

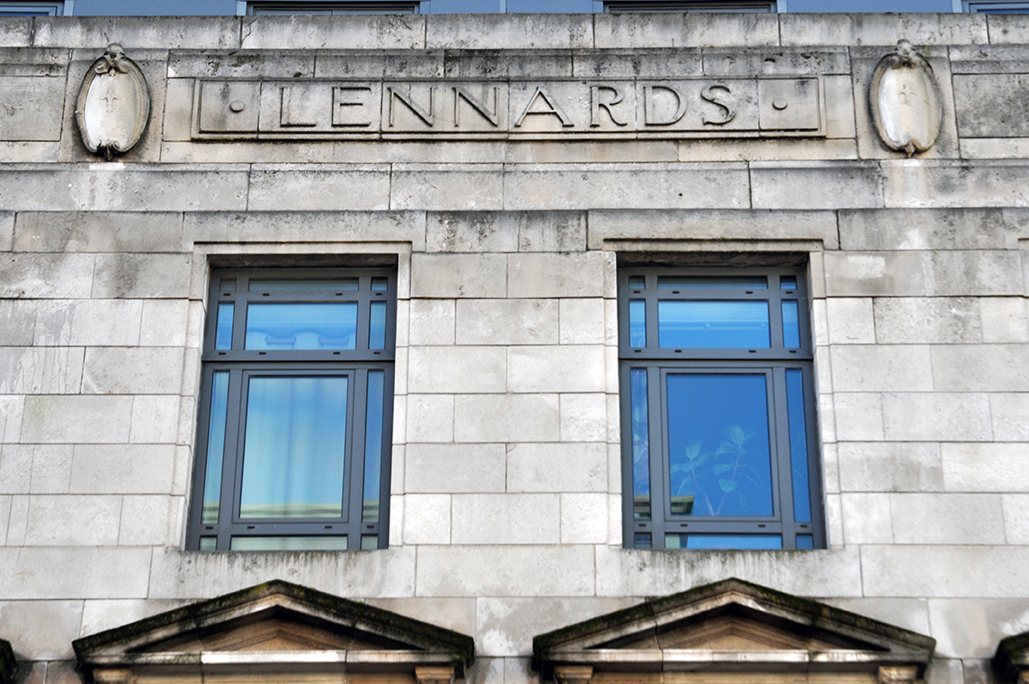

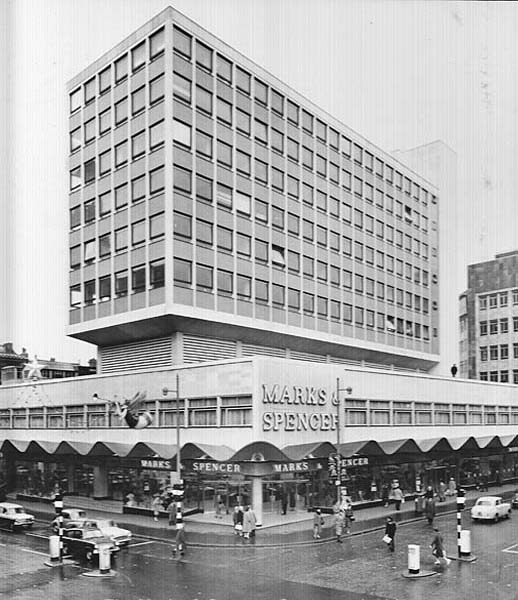

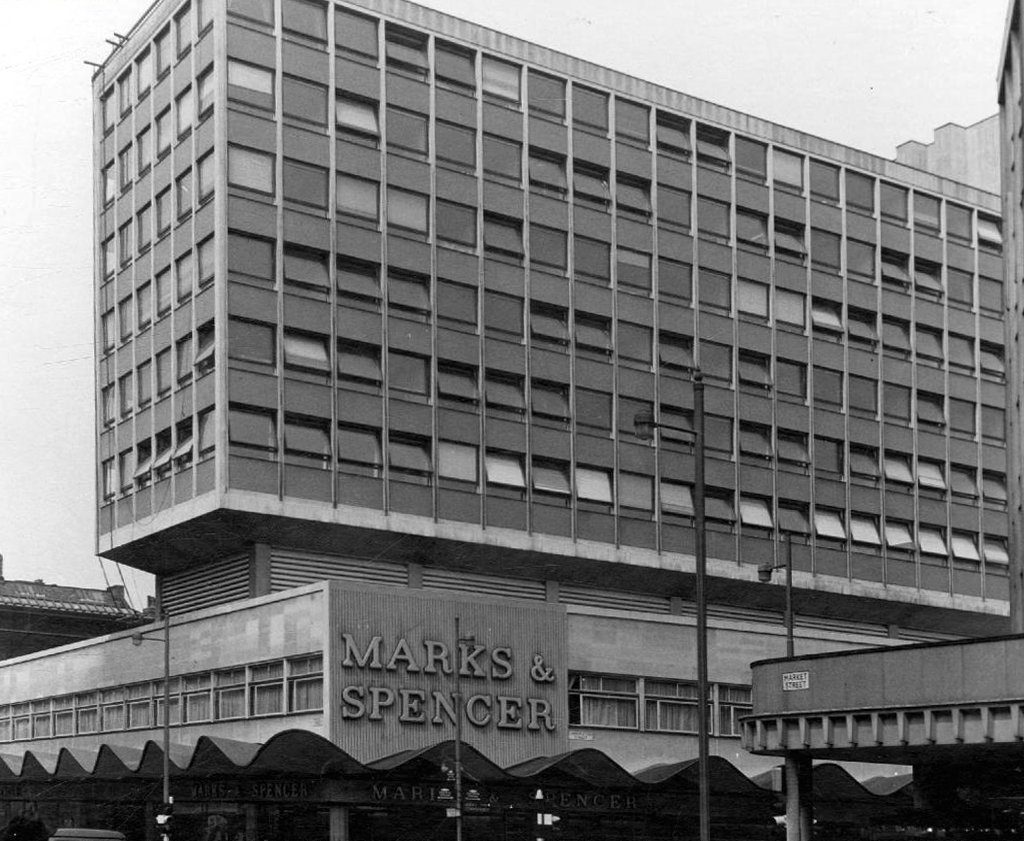

The Halifax Building was designed by the architecture firm BDP and constructed in 1968-74, as the headquarters for the Halifax Building Society and built with an unusually high budget. The rapid growth of the society over the twentieth century prompted the requirement for a new headquarters building, and in 1968 the aim of the architects was to design not only a practical building but a bold building for a confident client.

The building was Grade II listed in February 2013

In their report, Historic England comment that:

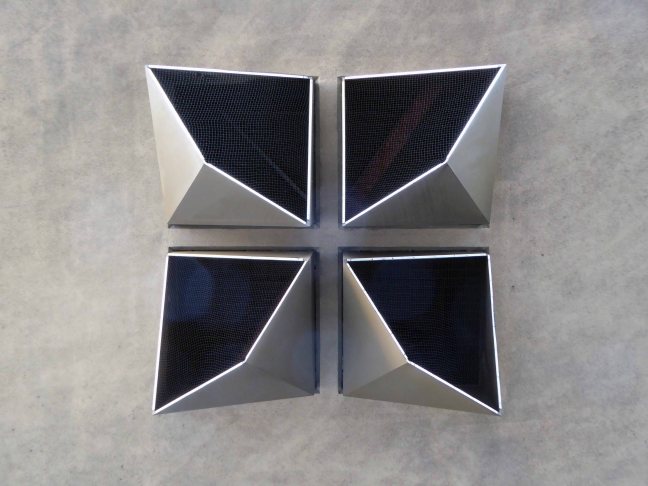

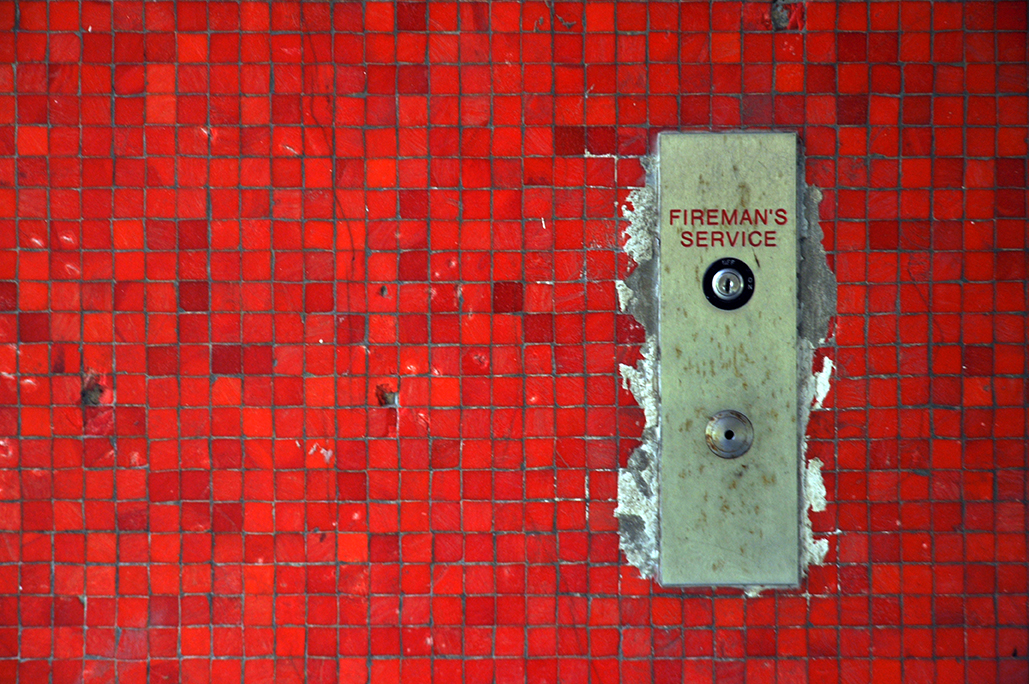

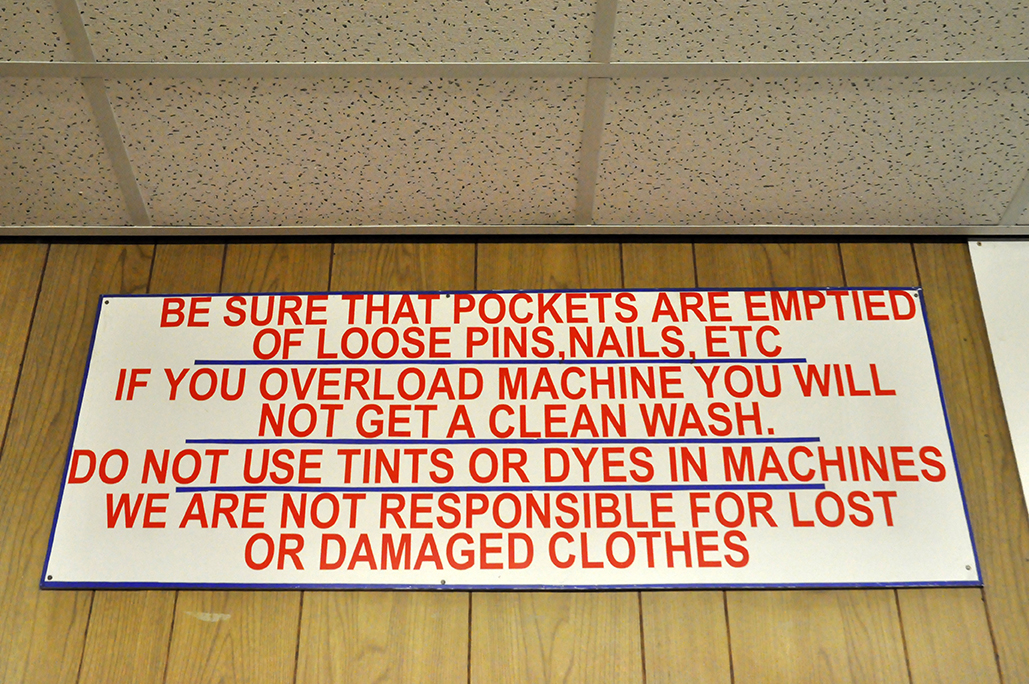

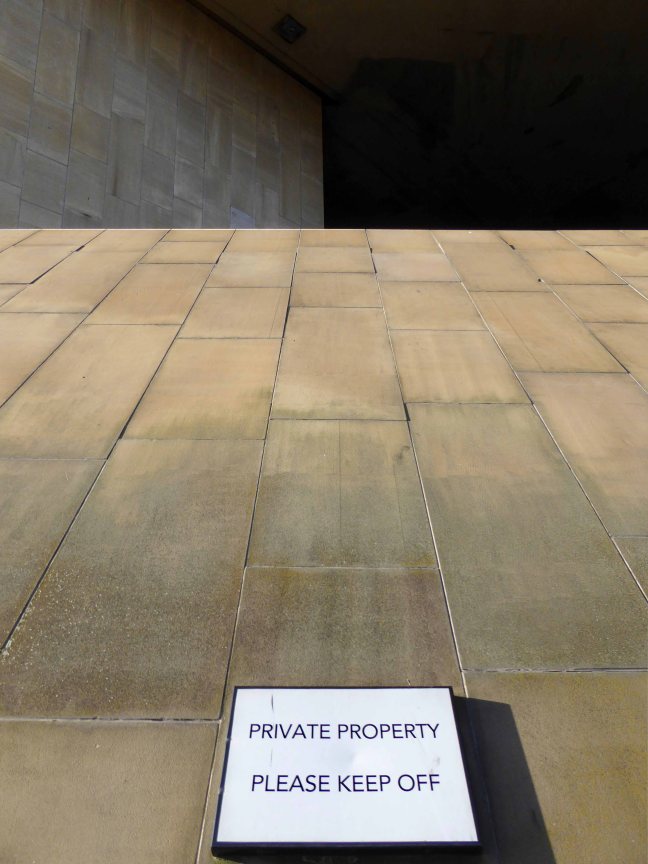

“Though necessarily large in scale, and centrally located in the town, the design is one of humanity, respecting both the townscape in which it was placed, and the employees it was to house…The high budget was reflected in the building’s finishes inside and out. Externally a limited colour palette and use of York stone cladding gave a homogeneity and showed consideration to the local character of the stone buildings of Halifax. Internally, materials were high quality and colour co-ordinated, with landscaping to both the public ground-floor spaces and the executive fourth floor.”

Ian Nairn thought well of it –

I wandered around amazed by the sheer mass of the main volume of the building, and the thin slithers of sunlight and blue sky which abutted its glass and stone skin.

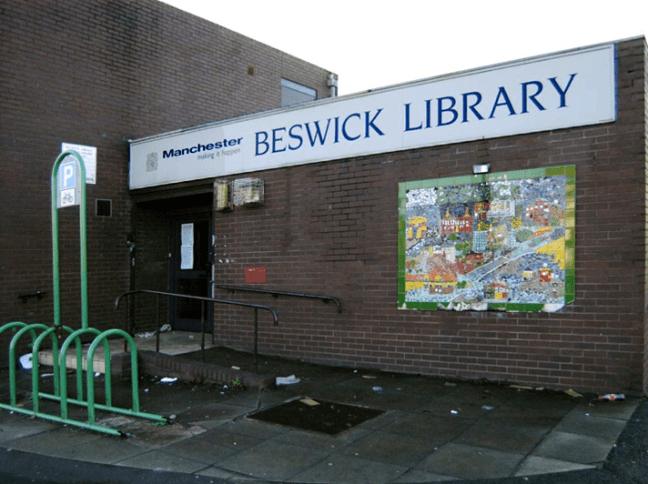

When approached by a curious security guard, I quickly allayed his initial fears, on production of my Manchester Modernist Society membership card and badge.

However fellow urbanists, take care, for the public is often mutually private and public at one and the same time, don’t step over the line.

Go take a look make of it what you will.