11 Styal Rd Wythenshawe Manchester M22 5WB

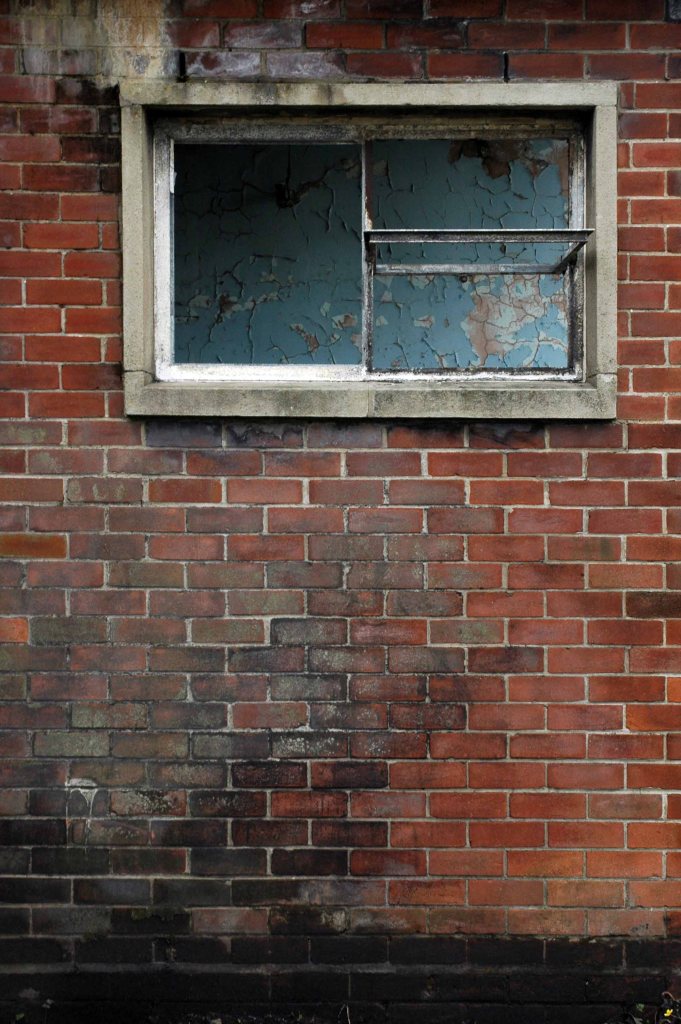

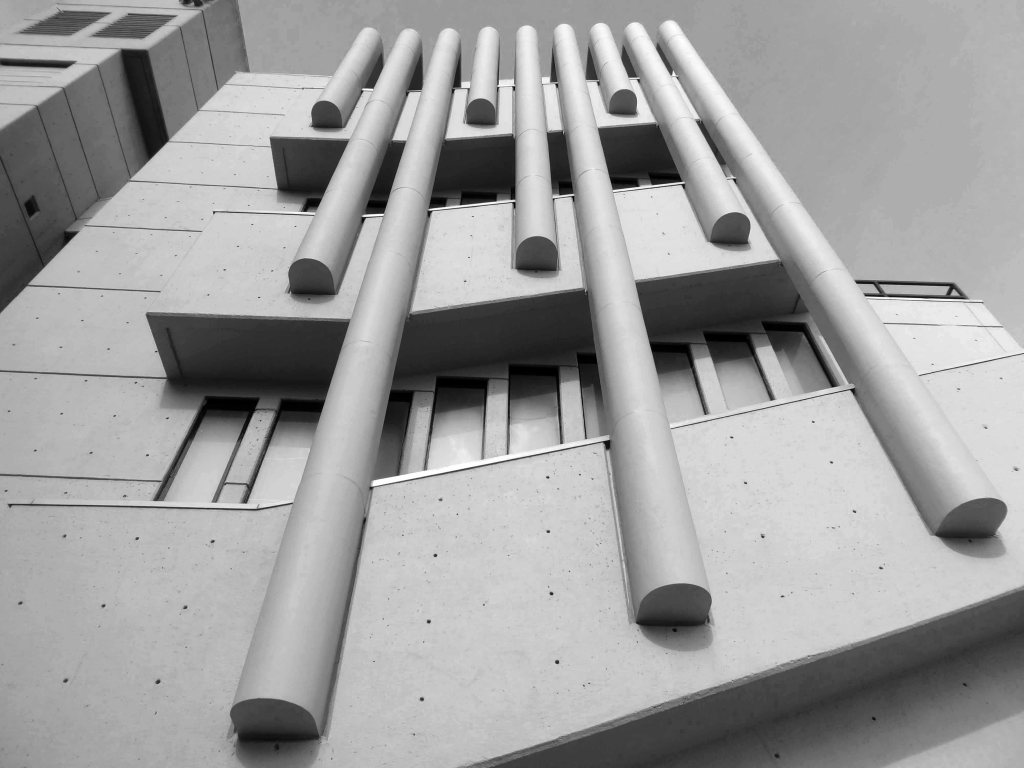

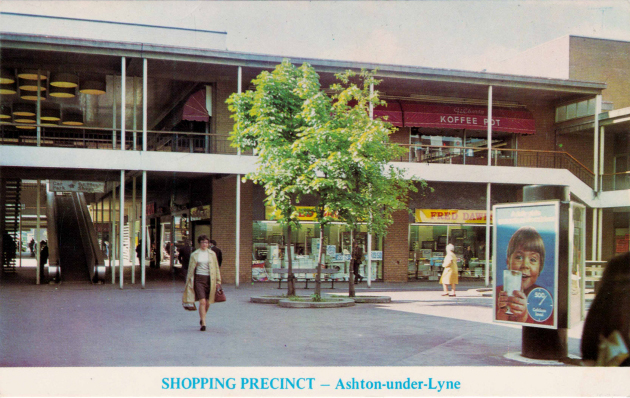

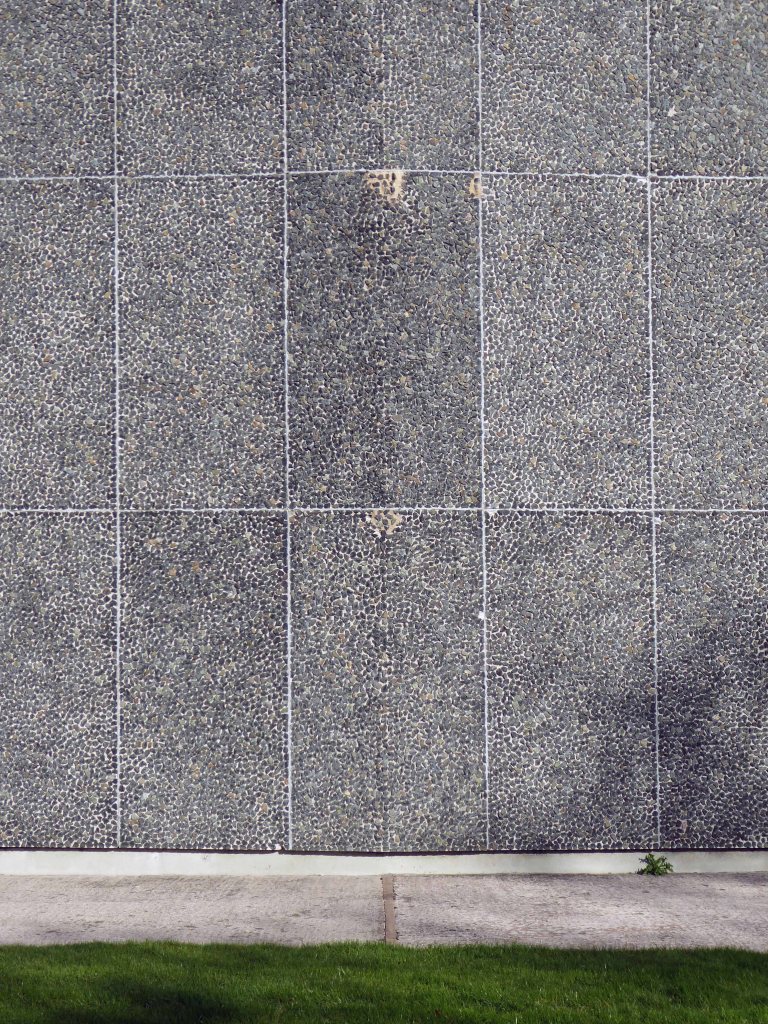

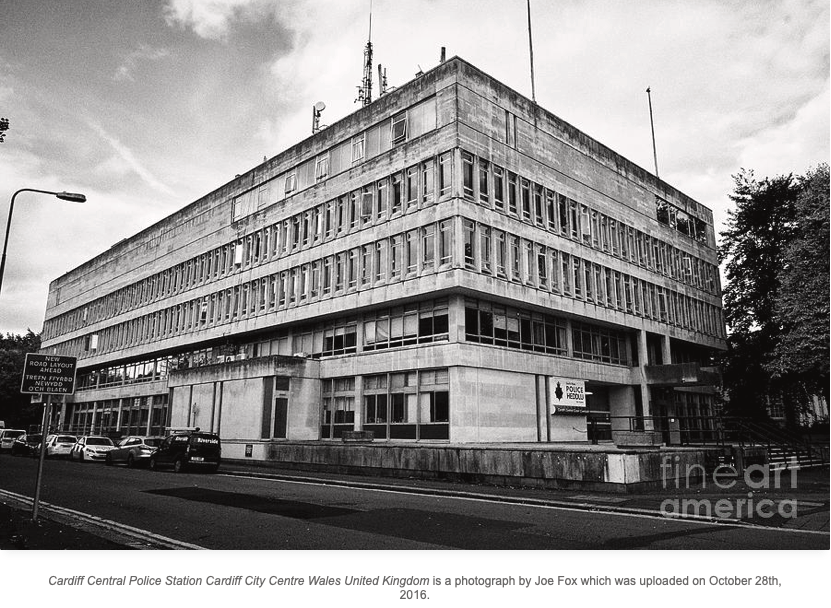

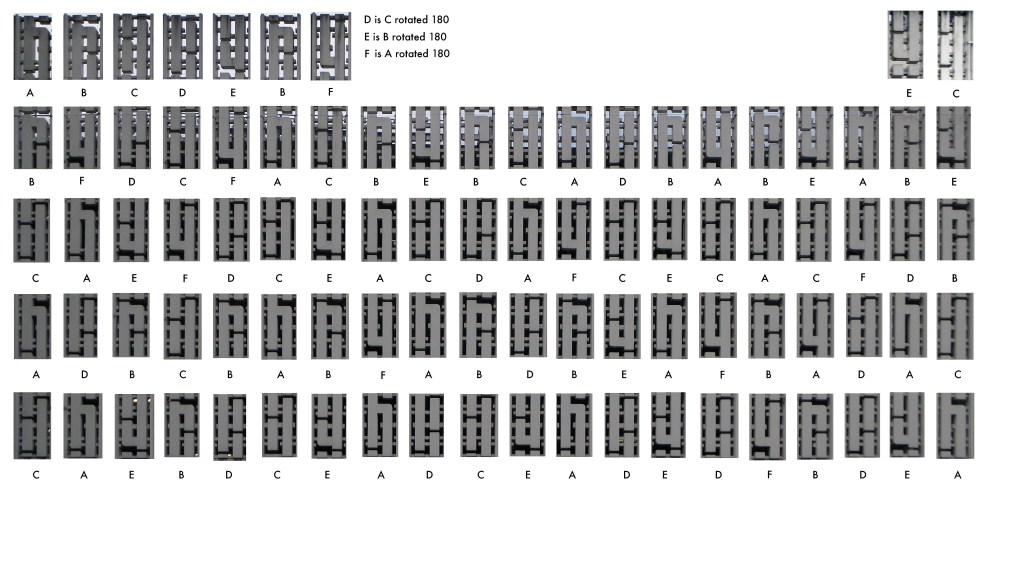

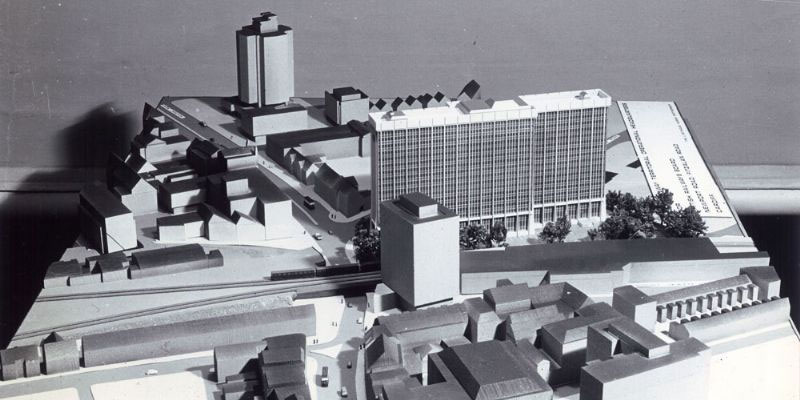

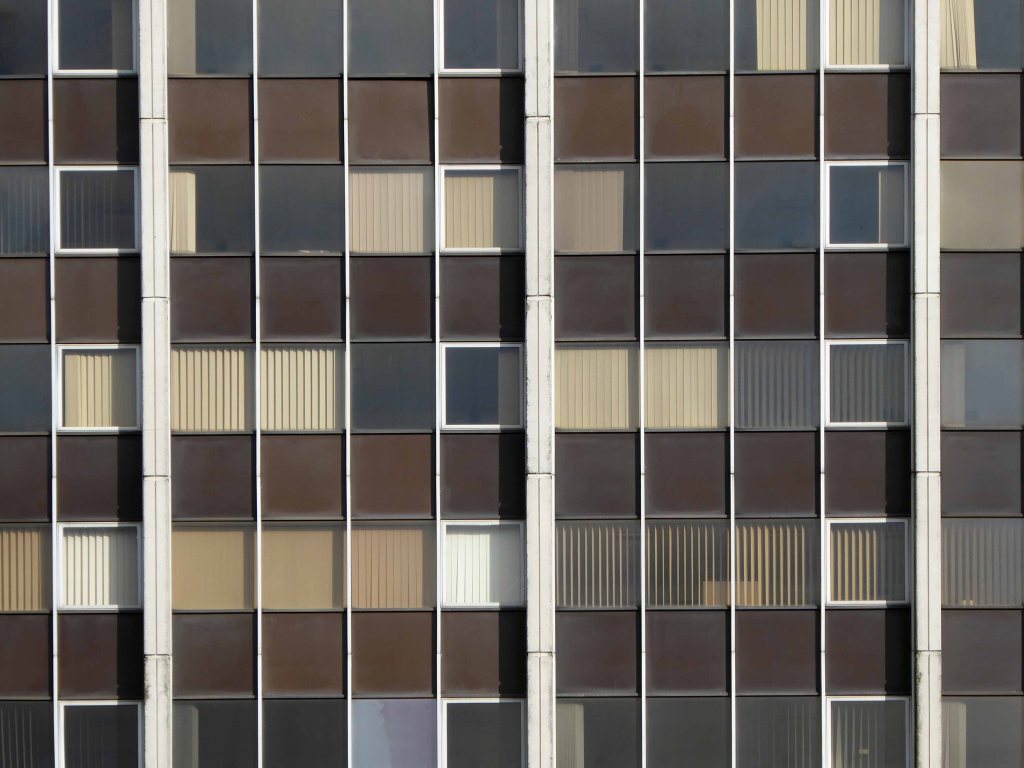

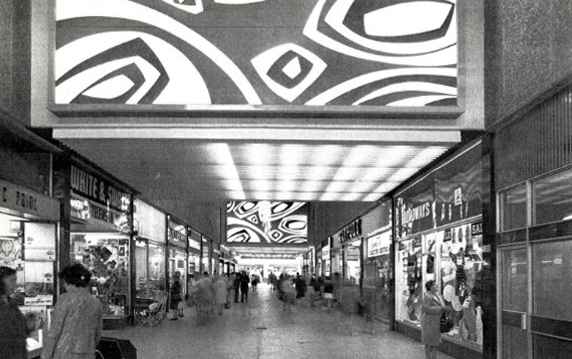

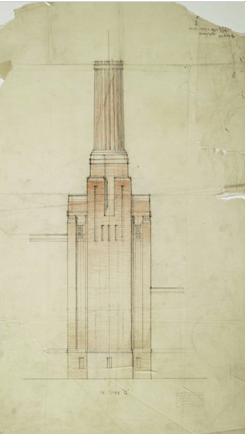

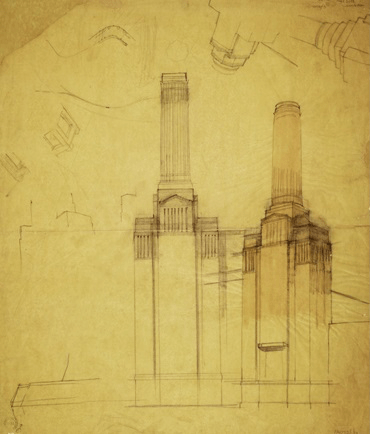

Renold Chains were once a huge firm employing thousands in south Manchester, their main factory at Burnage, now demolished to make way for a supermarket. This grouping was designed as the administrative headquarters for the company and was in receipt of an RIBA Architecture Bronze Medal in 1955. The scheme, of two parallel wings connected by a central hub running perpendicular, now seems fairly pedestrian, though still exudes some presence by virtue of the evident control in the design and construction of relief within the main façade. This building, though, actually points toward the moment where Cruickshank & Seward were turning, with the rest of the profession, toward new engineered, curtain walling solutions. The three storey glazed stair towers are made of a relatively fine steel section glazing bar and are clearly expressed at the ends of the blocks; these perhaps pre-empt the altogether more refined towers at the Renold Building and Roscoe Building of the Universities. The third floor boardroom was also positively expressed as a curved solid, cantilevered above the entrance canopy. That the building was developed in such close proximity to the airport has ensured its continued viability as office and conferencing space. The firm also delivered the adjacent building for the same client in the 1970s.

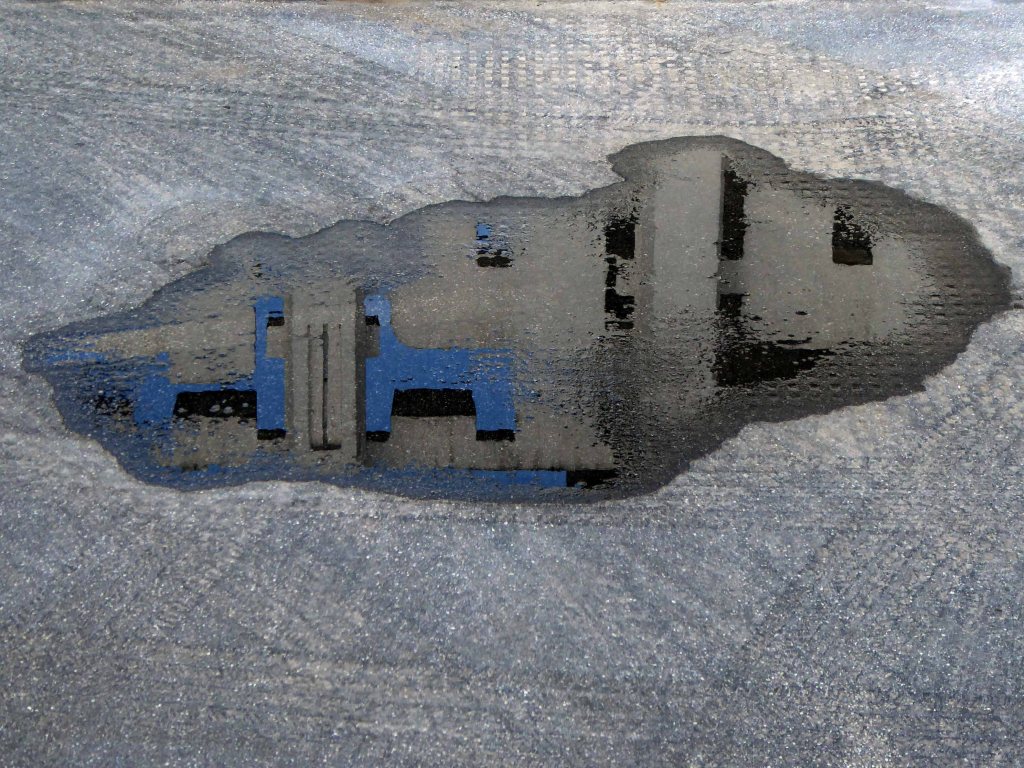

Four weeks into a pandemic – cycling somewhere else. I turned off and into the grounds of the former Renold House, currently trading as Manchester International Office Ccentre.

Manchester International Office Centre (MIOC) is a prominent landmark office building extending to some 100,000 sq ft which provides occupiers with high quality space ranging from suites of 450 to 8,000 sq ft.

The building has undergone a complete internal transformation with a total refurbishment of the reception and common areas. The office suites provide a superb working environment in line with the demands of todays occupier.

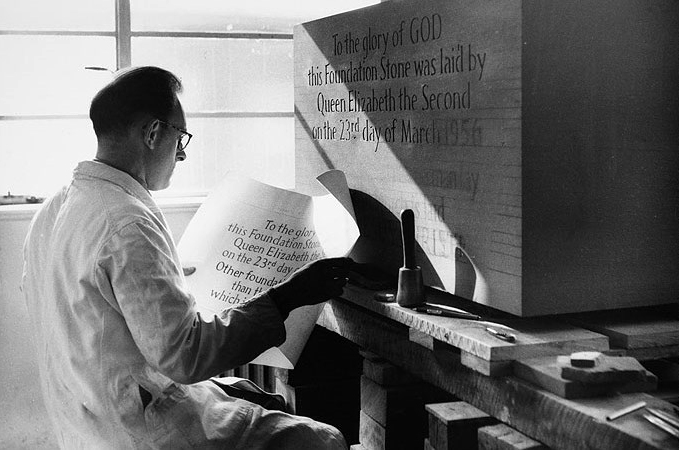

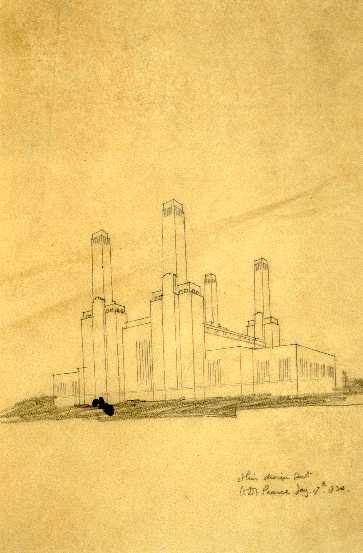

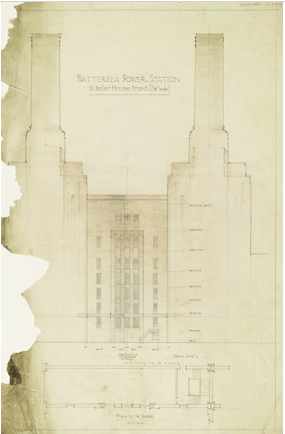

On arriving home I hungrily rustled up a few RIBA Archive images from 1954.

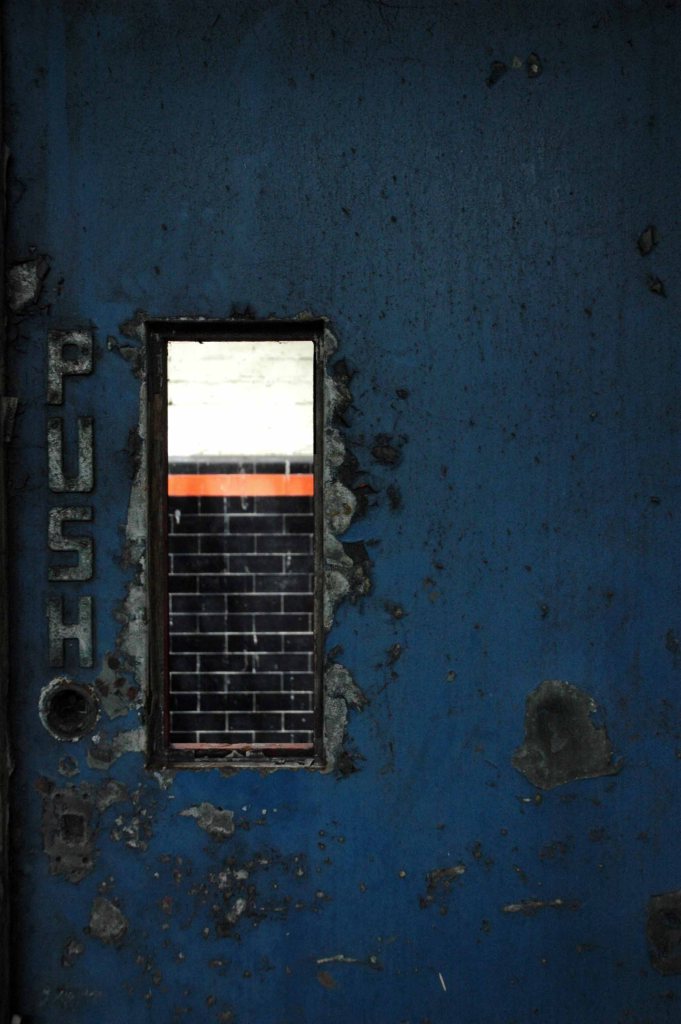

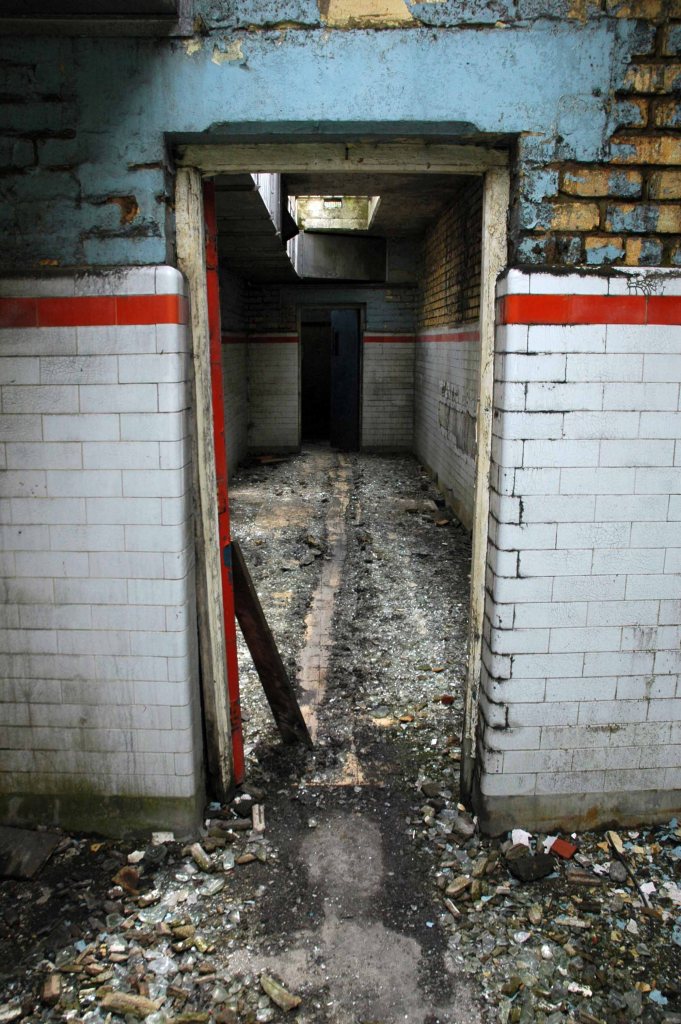

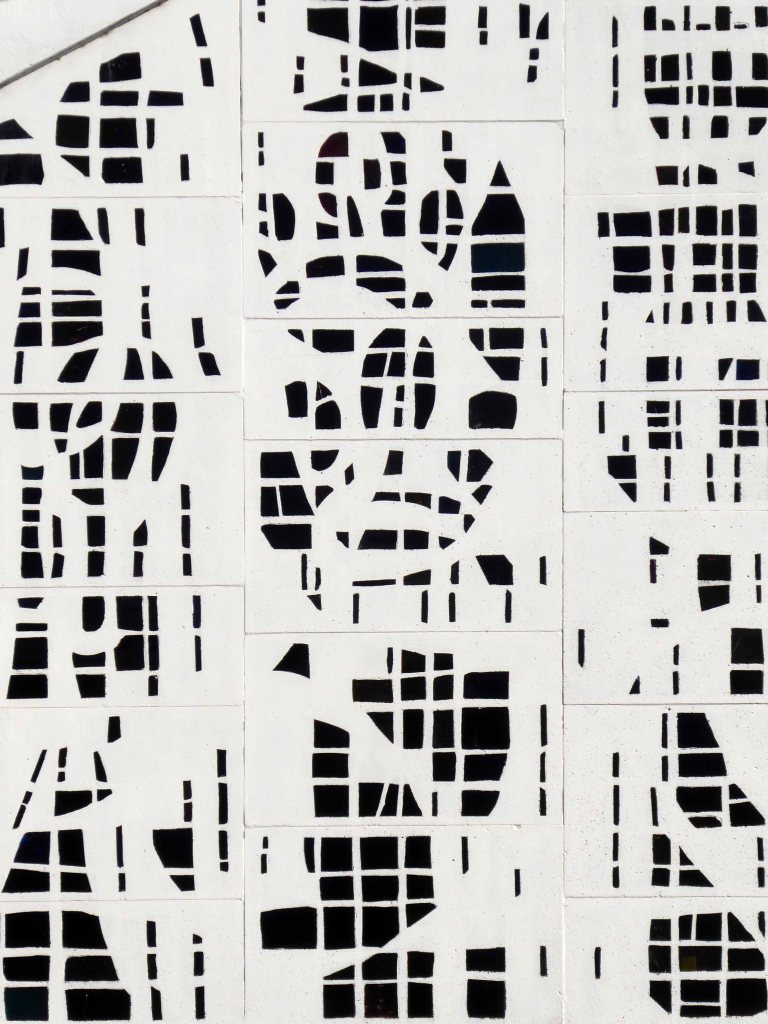

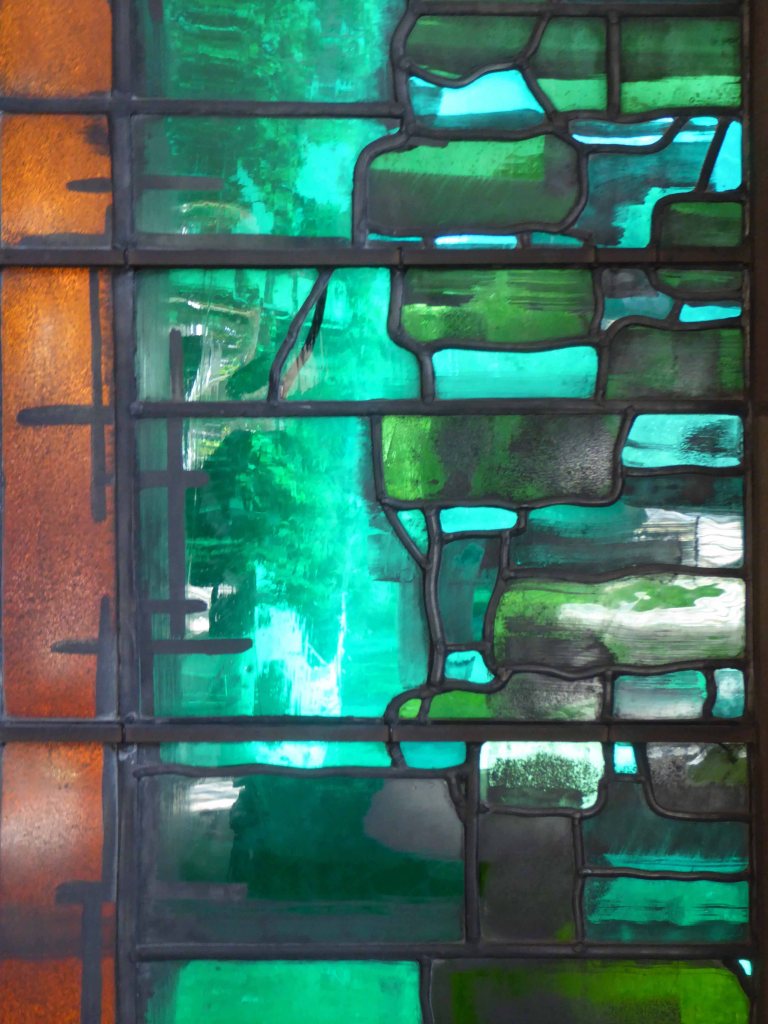

Much remains intact – though gone is the concrete grid and glass brick insertions of the 1954 central section – replaced with a slick glass and steel skin.

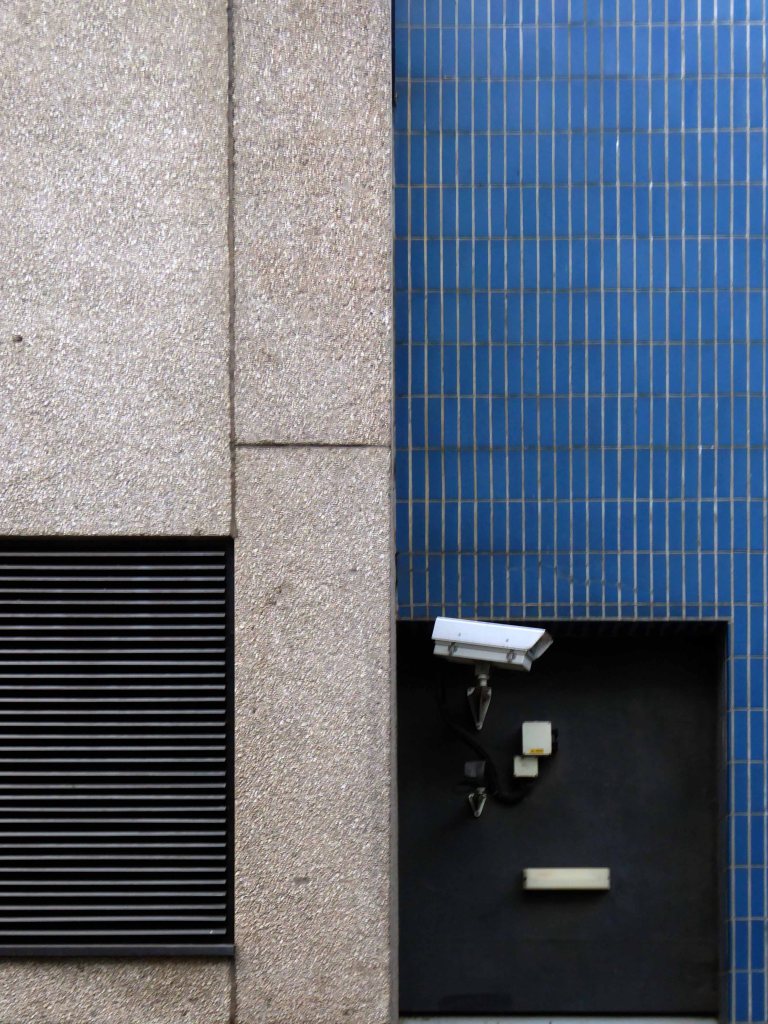

And there are unpleasant intrusions made by the fitting of contemporary security and lighting – using intrusive exterior conduit.

It’s a sunny day with a southwest light – there’s nobody about, let’s take a look around.