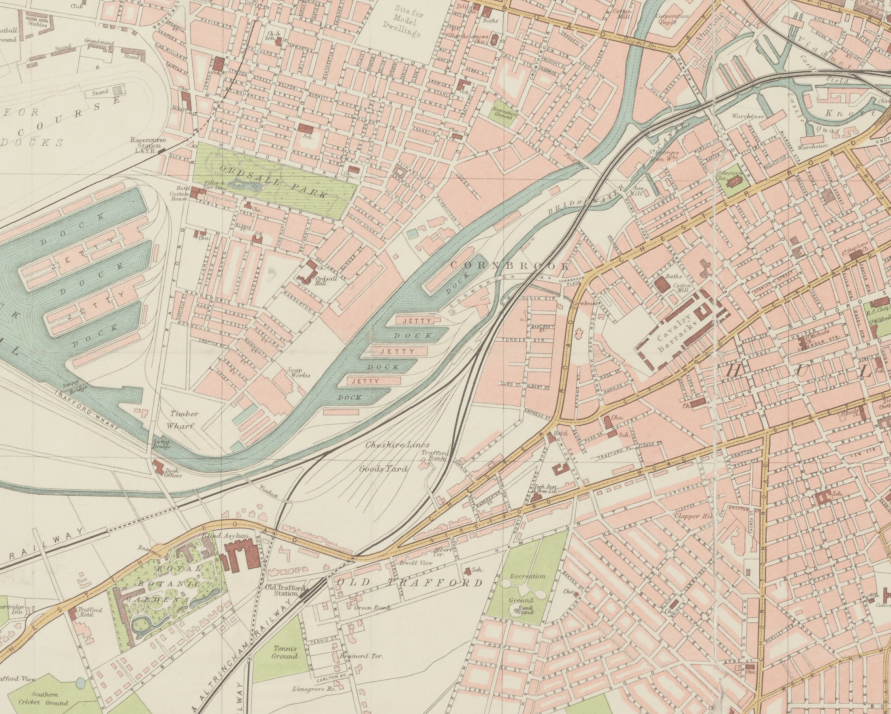

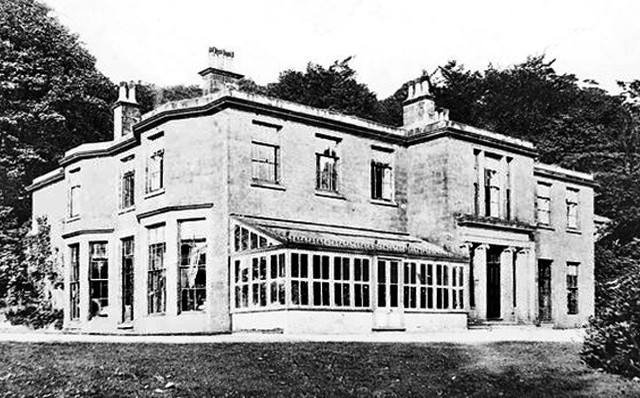

First there was a house.

A Grade II listed country house, now divided into two dwellings. c1812. Ashlar gritstone. Hipped slate roof with leaded ridges. Various ashlar triple stacks with moulded tops. Moulded cornice and low parapet. Two storeys, central block with recessed long wing to east, orangery to west.

Currently trading as a quick getaway country cottage

This Grade II listed manor house is set within 14 acres of natural grounds, together with the occupied adjoining servants’ wing, and has been sympathetically converted, retaining many original features to provide comfortable accommodation for families wishing to meet up for that special family occasion, and wi-fi is available in the living room.

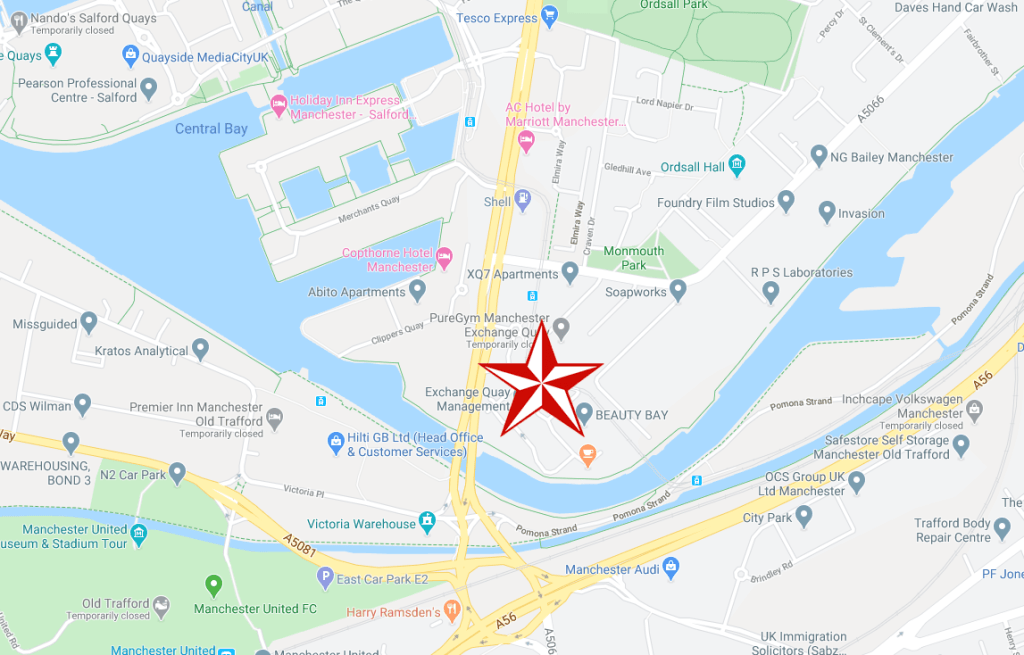

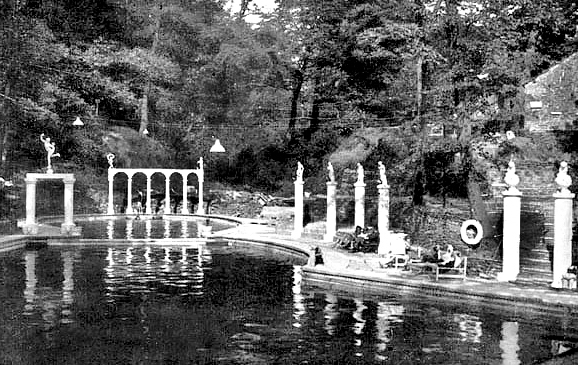

Then came a pool:

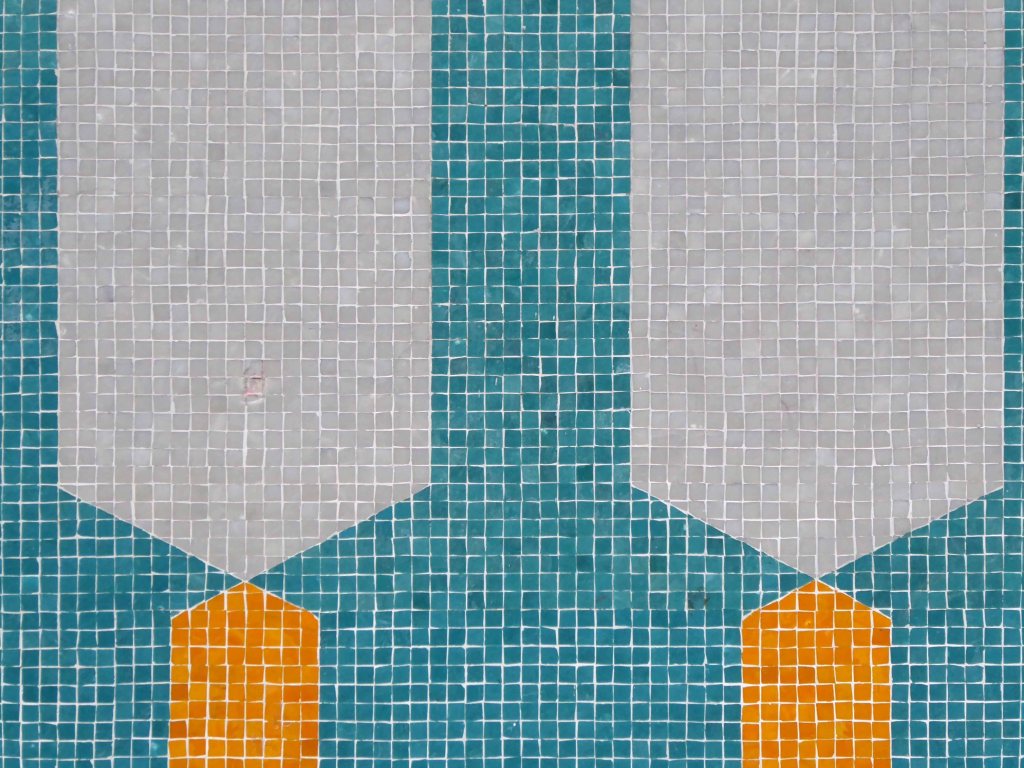

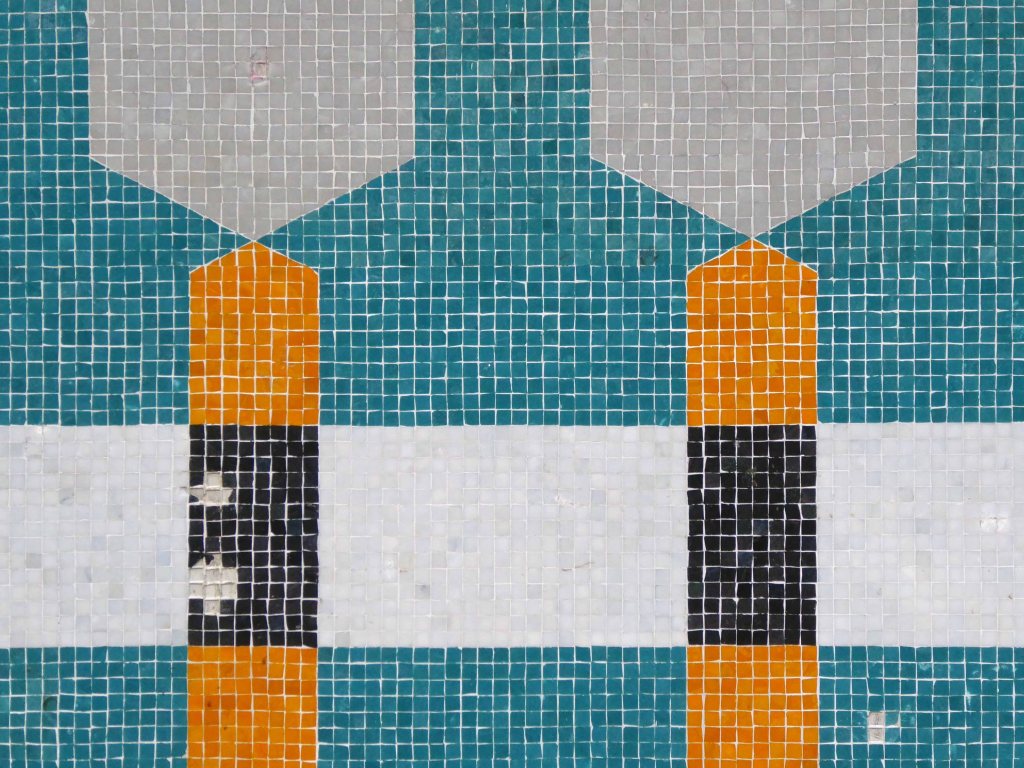

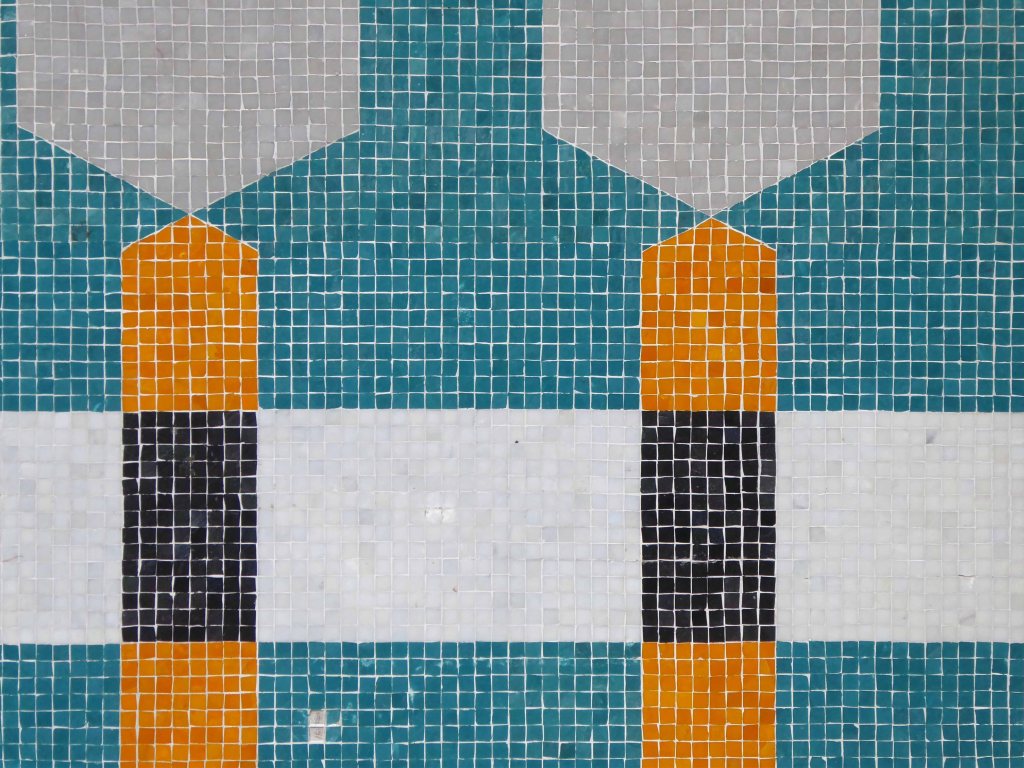

Previously a private pool belonging to a country club in the 1930’s it later opened to members around 1938 who paid a small fee for its use. The pool is fed by a mountain stream and the water is reported to remain cool throughout the year. In the 1940’s/50’s locals recall the pool being open to the public where it cost a ‘shilling for children and half a crown for adults’ entry. During storms in 1947 the pool was badly damaged and reportedly ‘never the same again’ but postcards in circulation in the 1960’s provide evidence that the pool remained open at least until then.

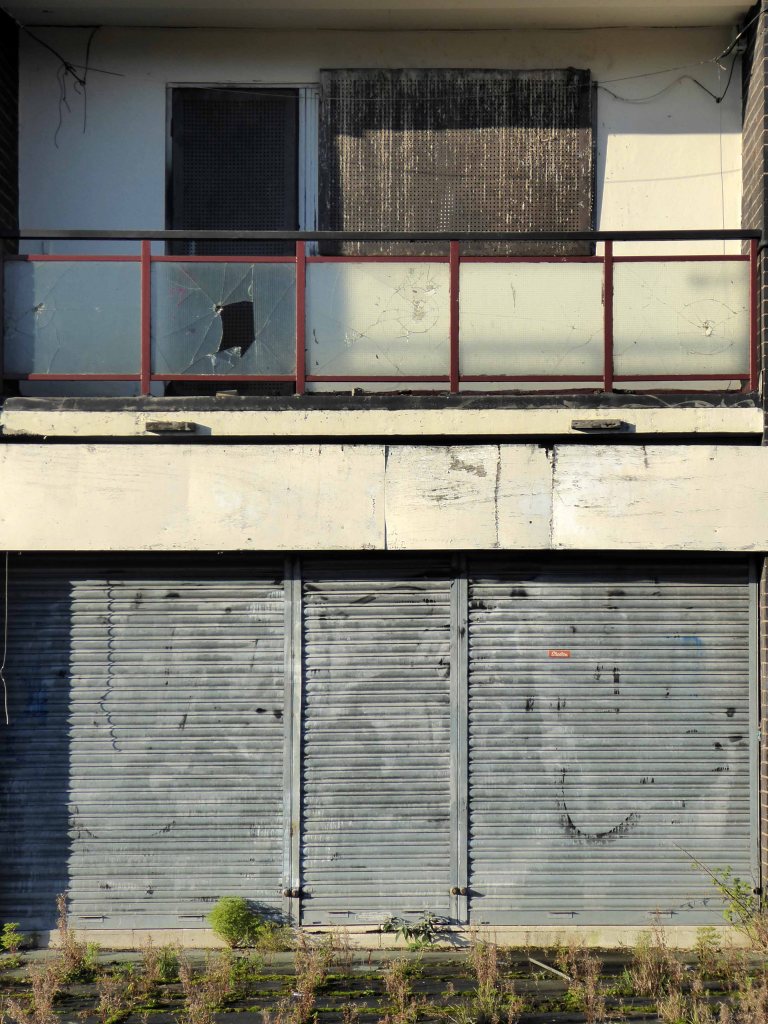

Now it sits abandoned and hidden in the woods.

I went there in my early teens late 60’s the pool was still intact, well used and well cold. I remember chilly changing rooms with duckboards on concrete floors, a small café with pop and crisp if you had the pennies.

Most of all the simple joy of emersion in clear moorland water, on long hot summer days long gone.

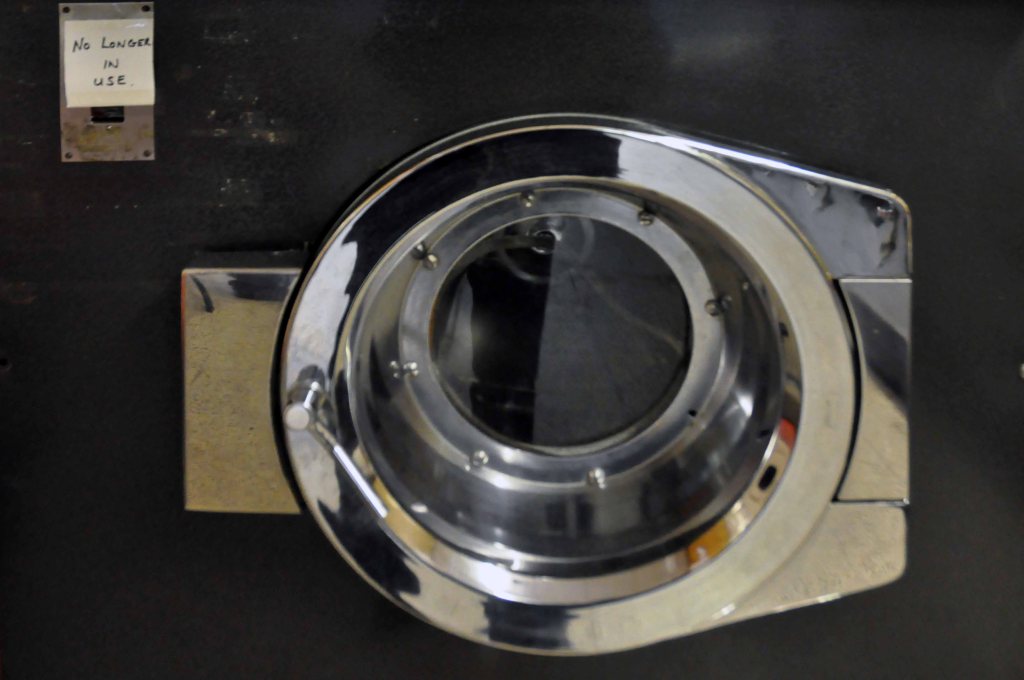

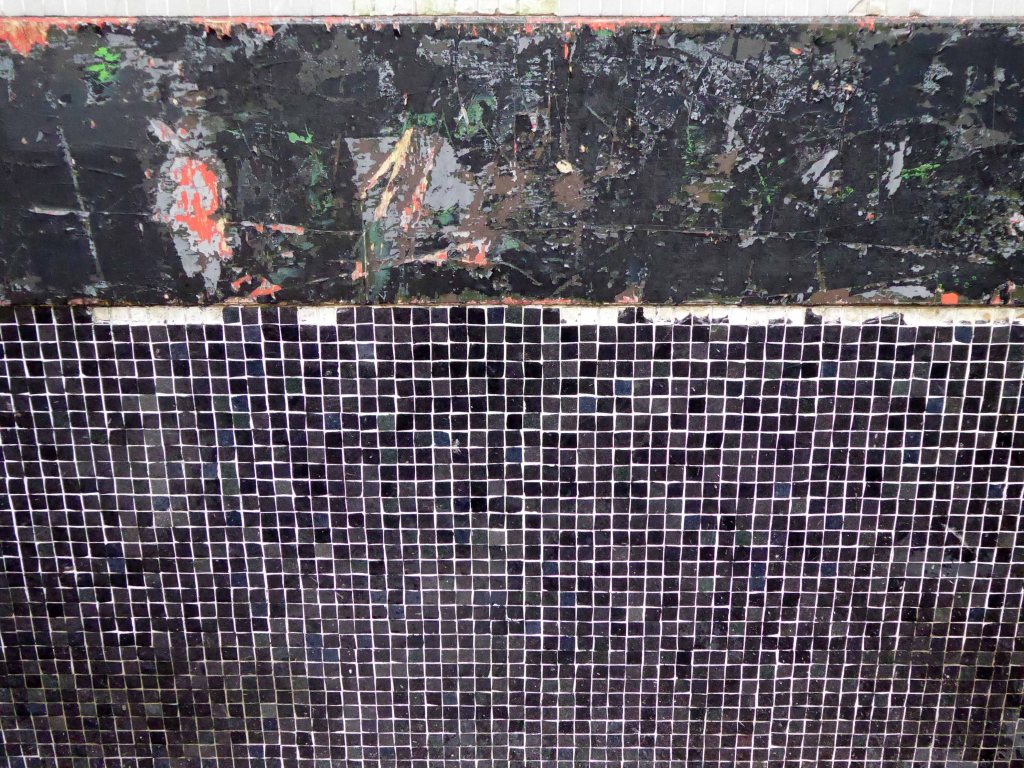

Revisiting in April 2014, following a misguided scramble through brambles, it was a poignant reunion. The concrete shells of the pillars and statuary crumbling and moss covered, the waters still and occluded.

It sure it has subsequently been the scene of impromptu fashion shoots and pop promo videos, possibly a little guerrilla swimming. Though sadly it largely sits unused and unloved – let’s take a look around: