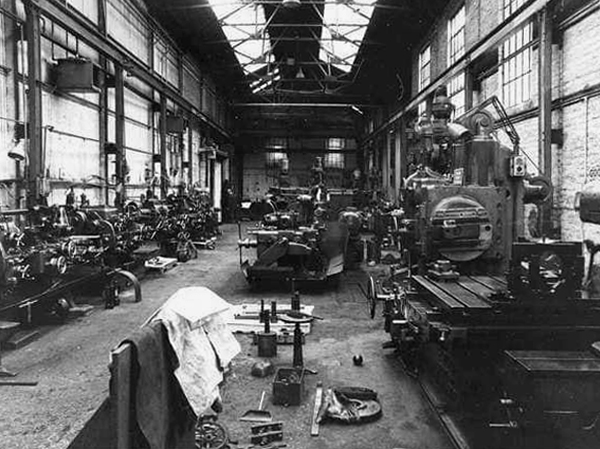

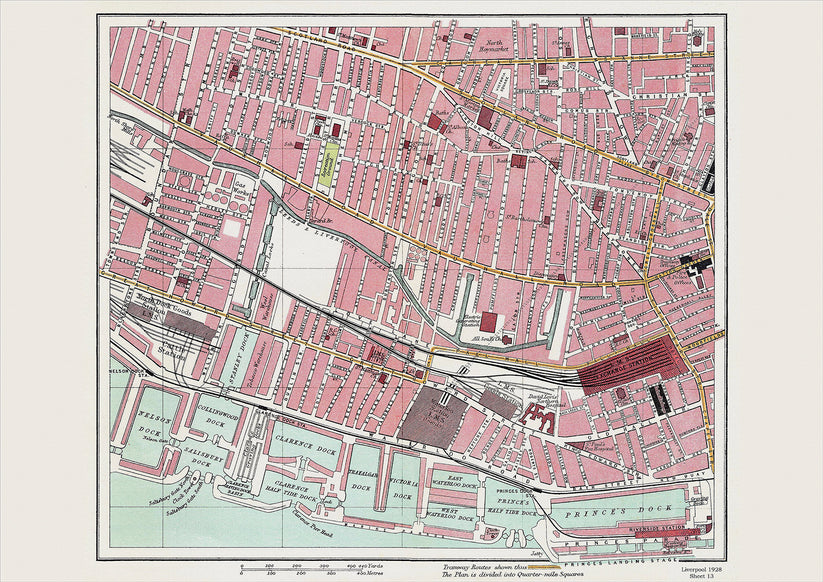

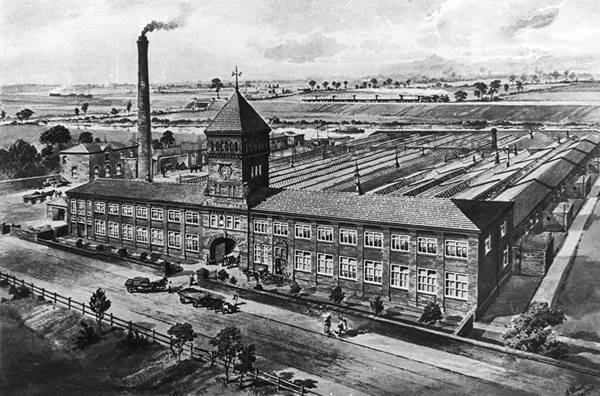

Manchester Guardian Printing Works owned by Taylor Garnett & Evans & Co. Ltd- a view of factory dated 1902.

Lithographic Printing Dept 1902.

CWS Printing Works – formerly the Guardian Print Works showing a view from the road dated 1972.

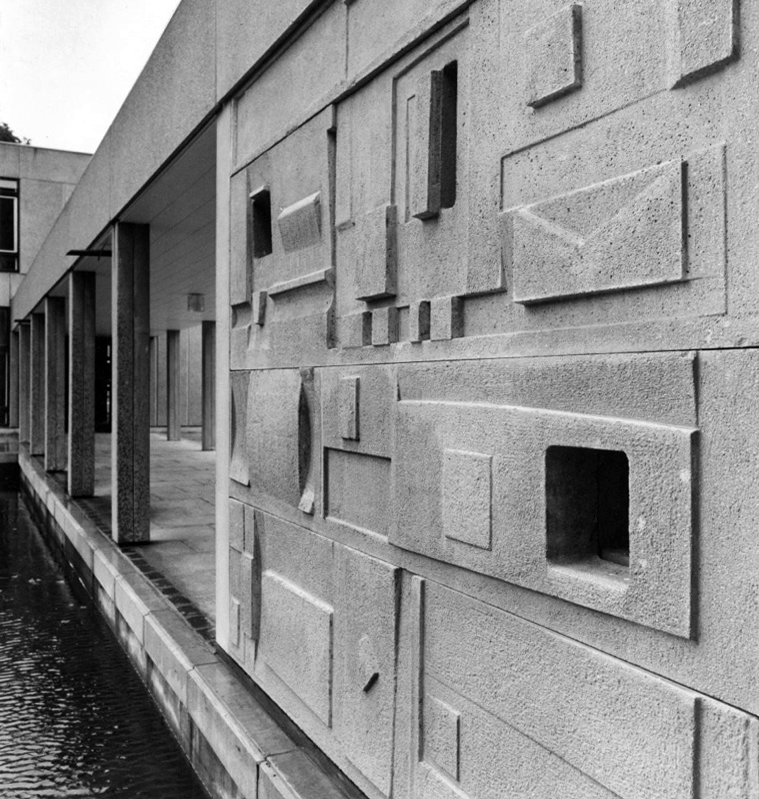

CWS Printing Works showing a rear view with canal in the foreground.

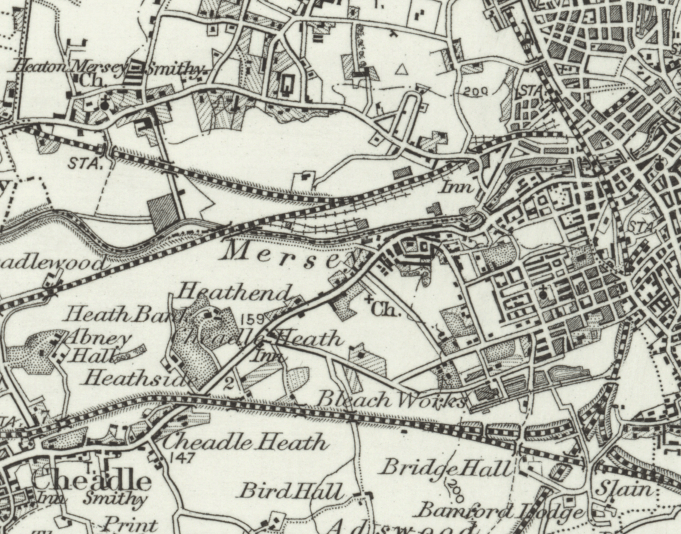

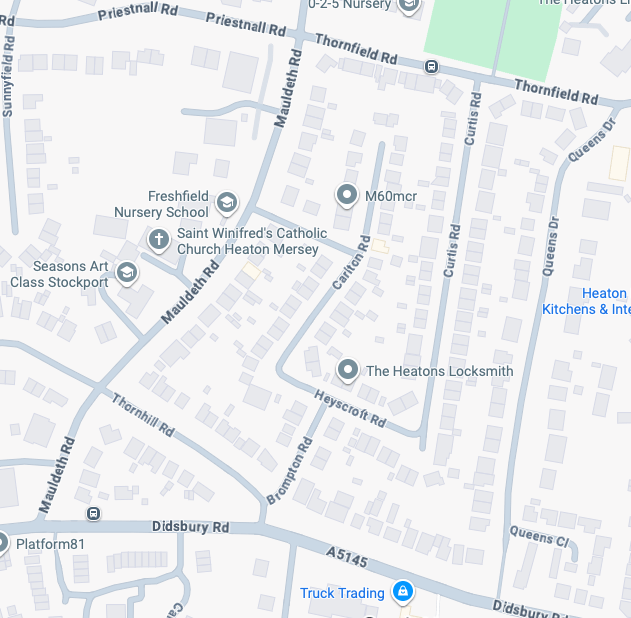

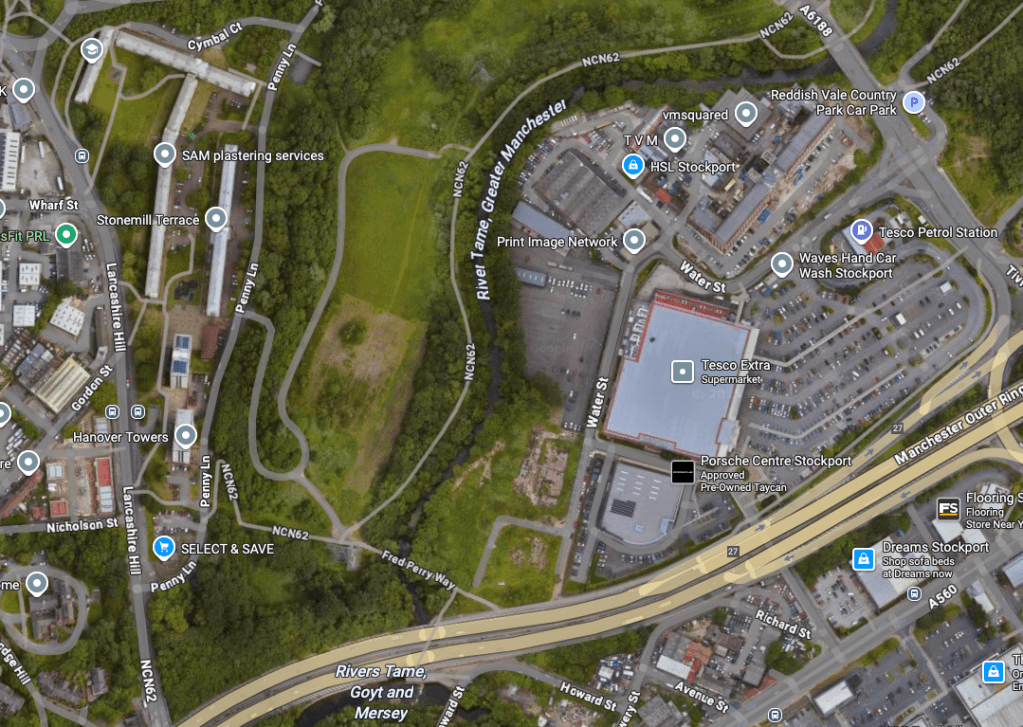

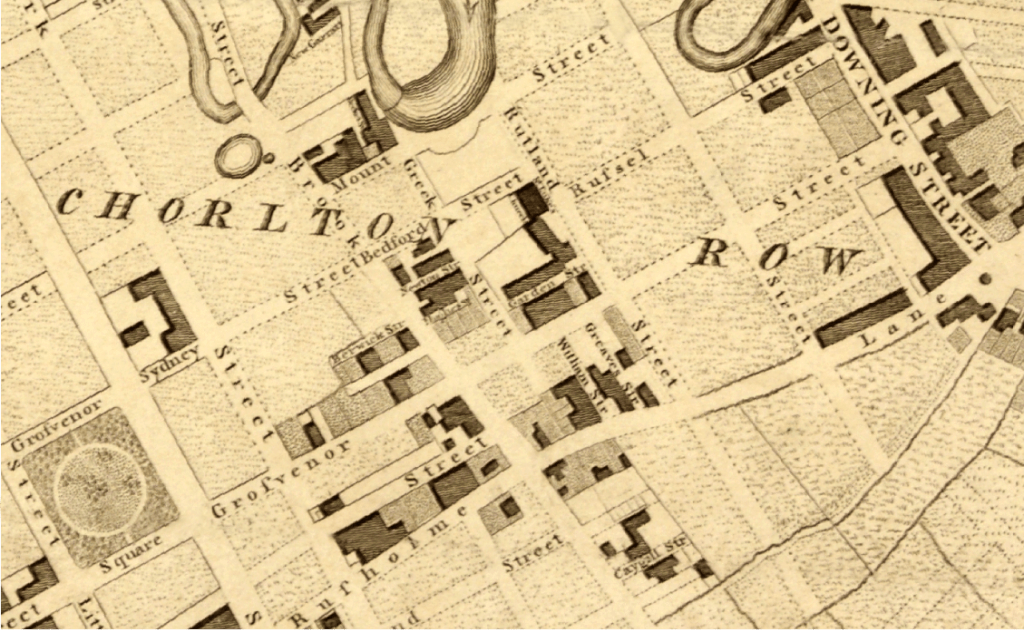

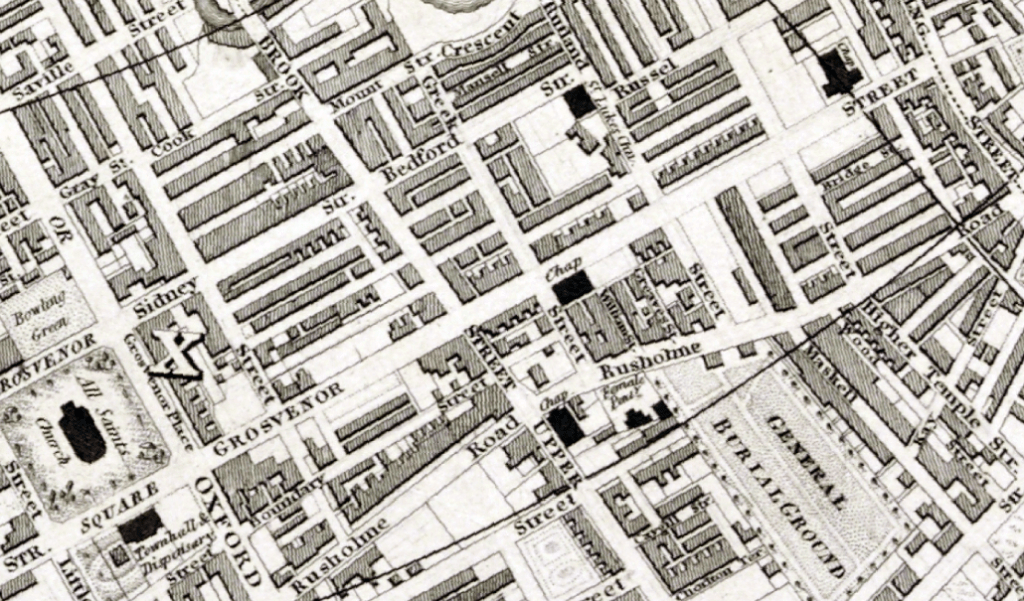

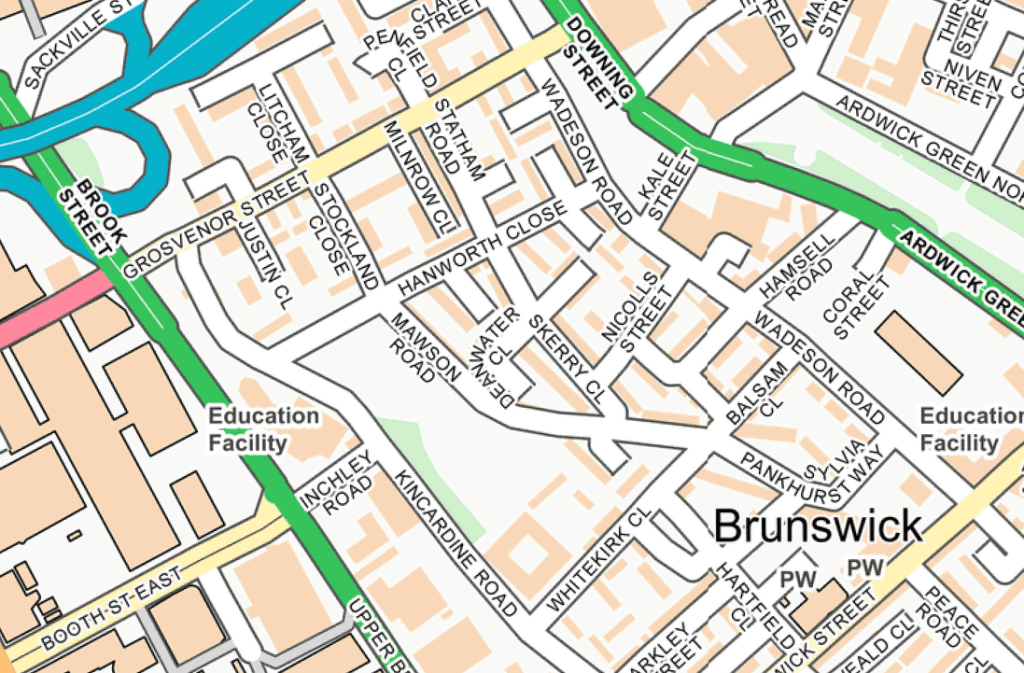

The Stockport Branch Canal was a five mile branch of the Ashton Canal from Clayton to Stockport.

An important cargo was the supply of grain to William Nelstrop & Company’s Albion Corn Mill at Stockport Basin.

In its early days there was passenger carrying on the Ashton Canal and one of the routes was between Manchester and Stockport.

Commercial carrying ceased in the 1930s but it lingered on into the 1950s’ as a barely navigable waterway. At one stage in the 1950s it was dredged but this improvement did not attract any traffic. Stockport Basin was the first section to be filled in but it was not until 1962 that the canal was officially abandoned by the British Transport Commission, who had been responsible for it since 1948.

It took many years to fill in and this was a disagreeable procedure for people living along its length.

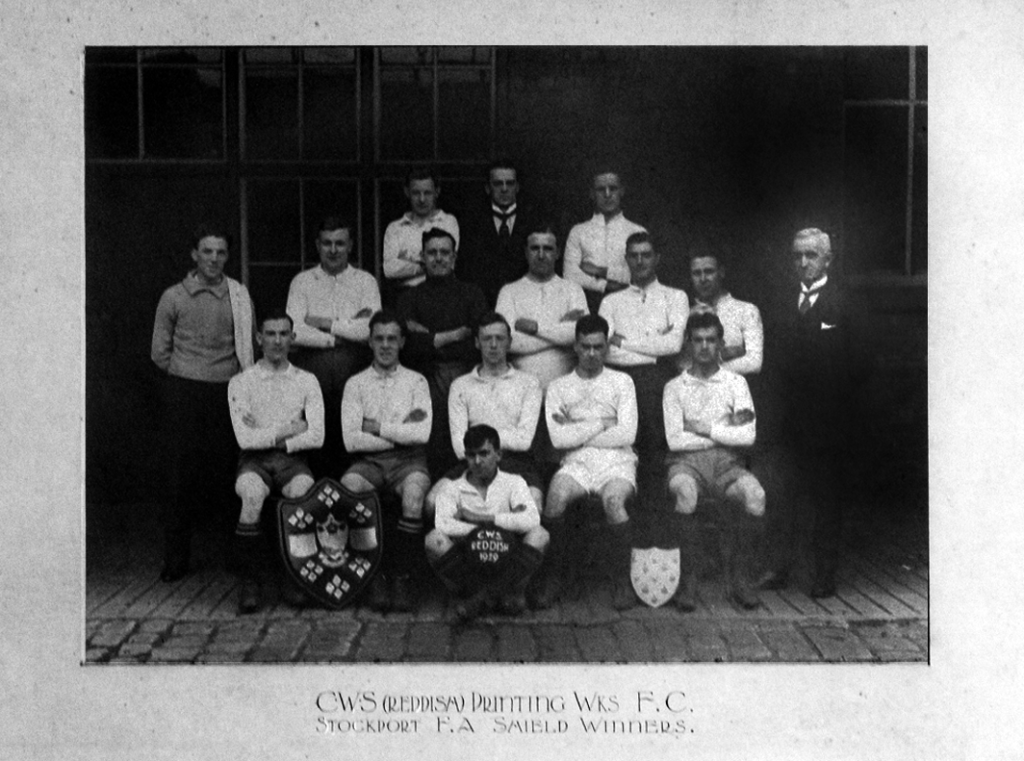

Archive Photographs – Stockport Image Archive.

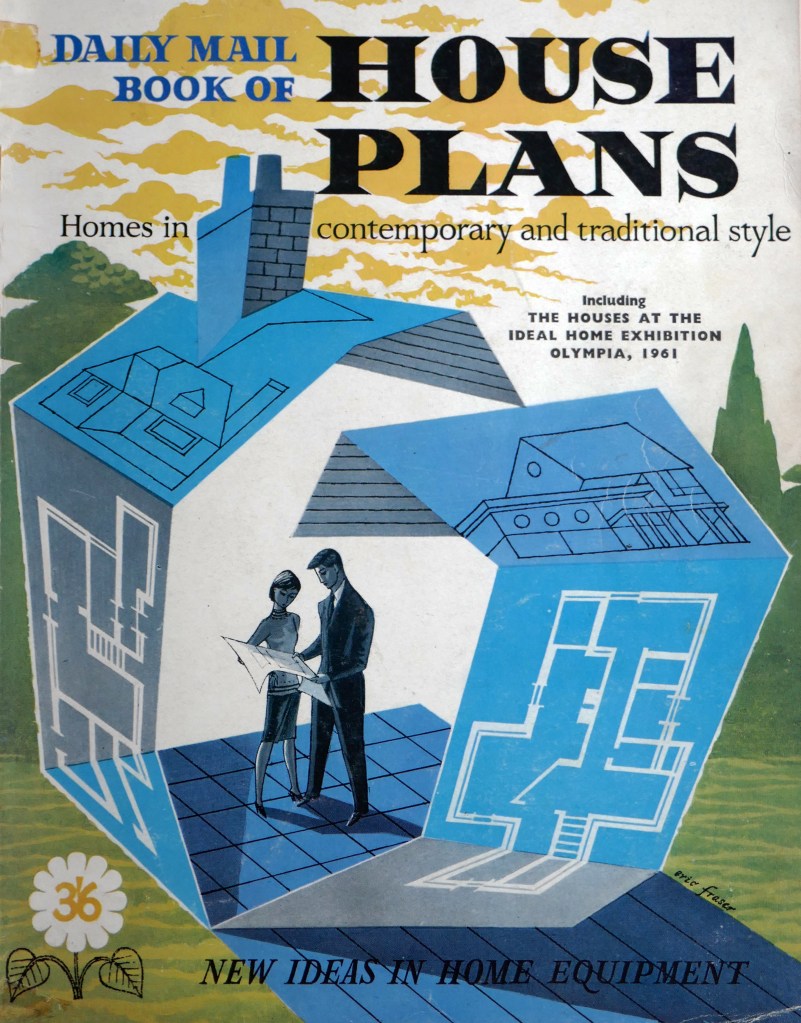

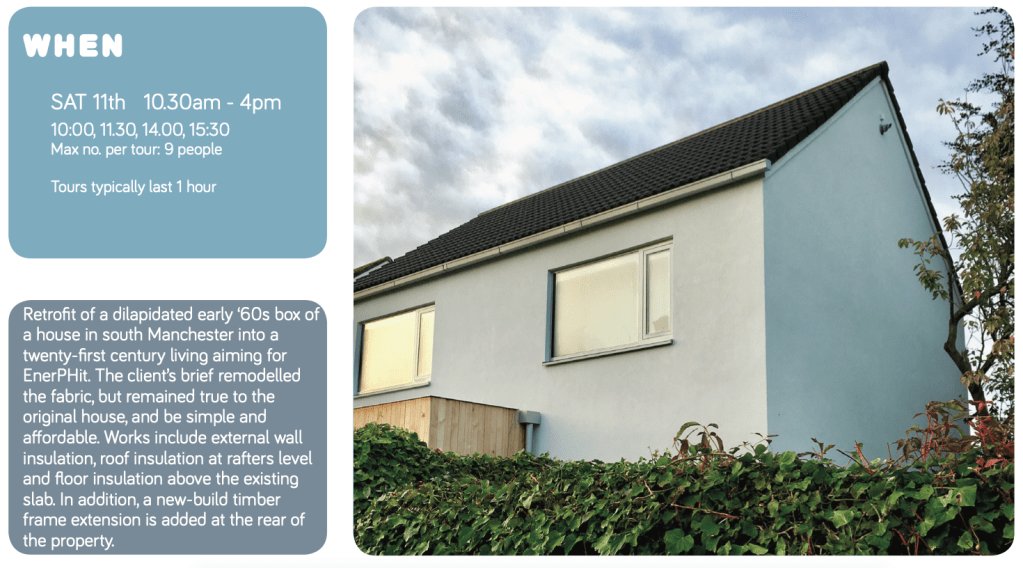

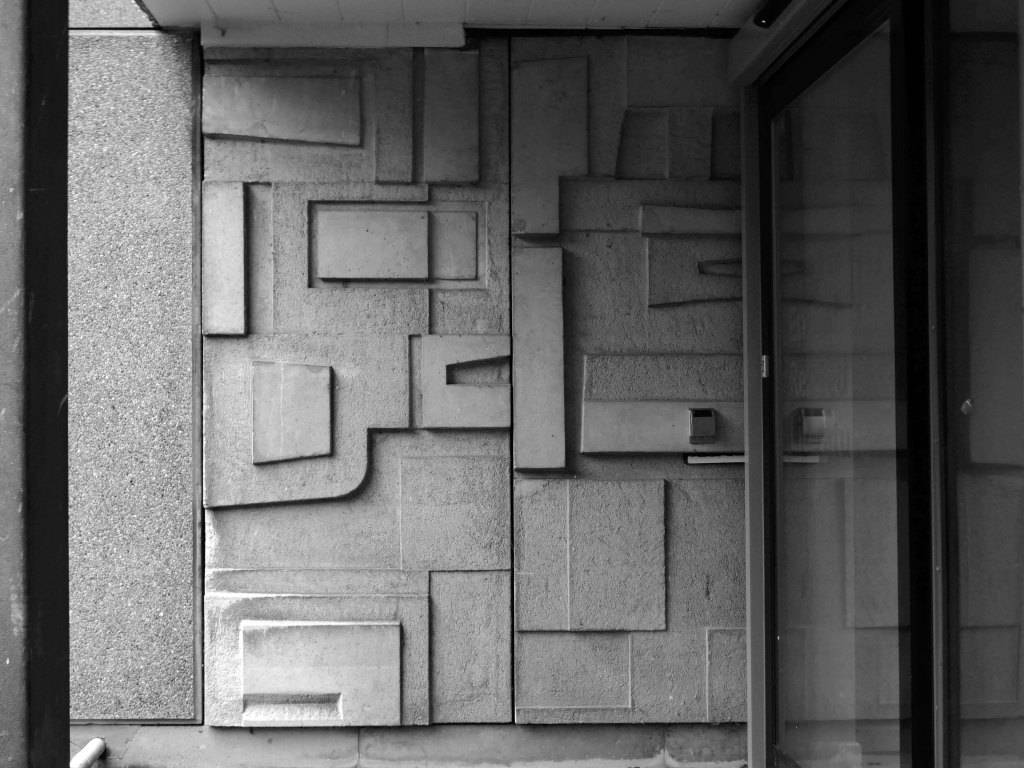

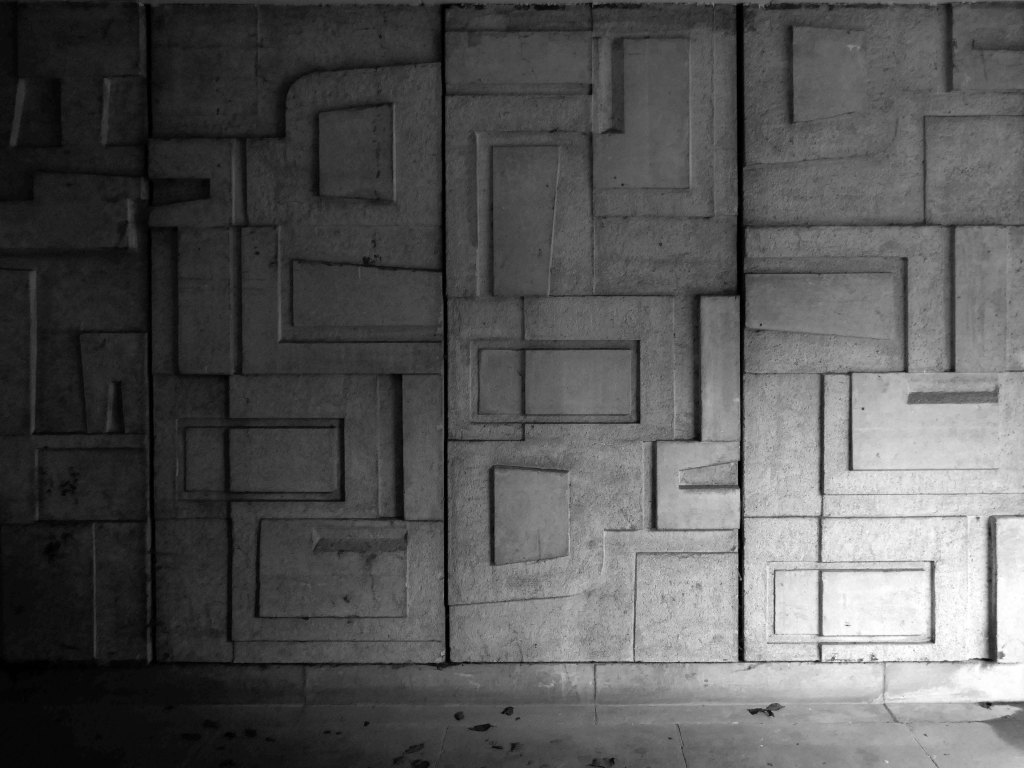

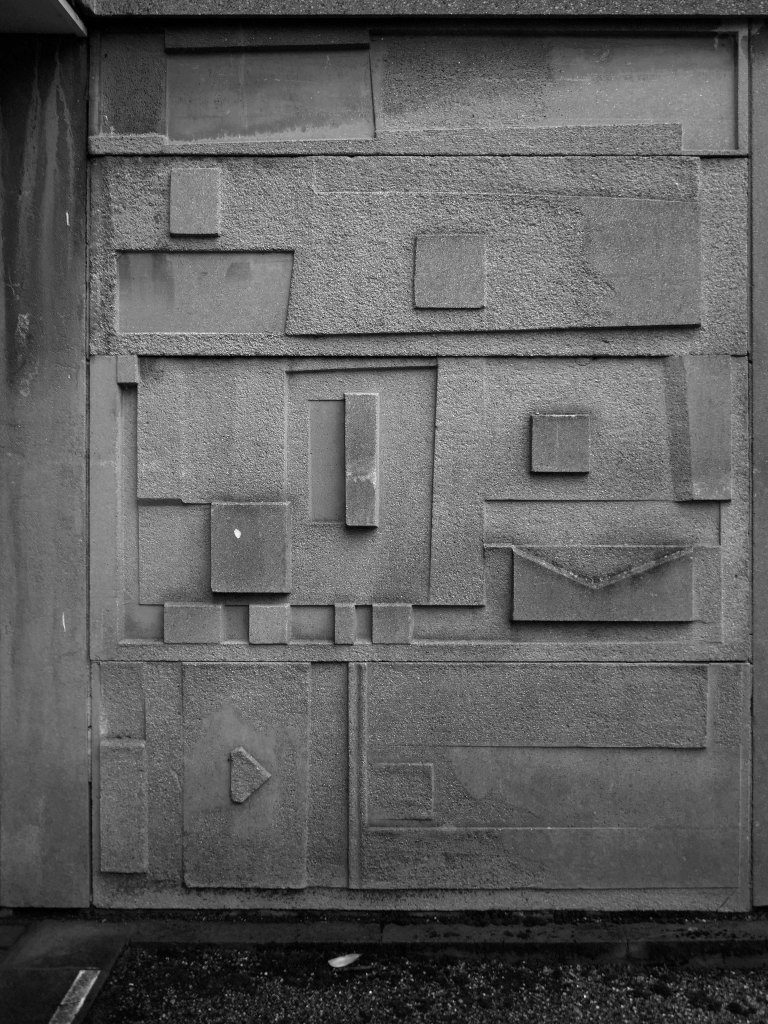

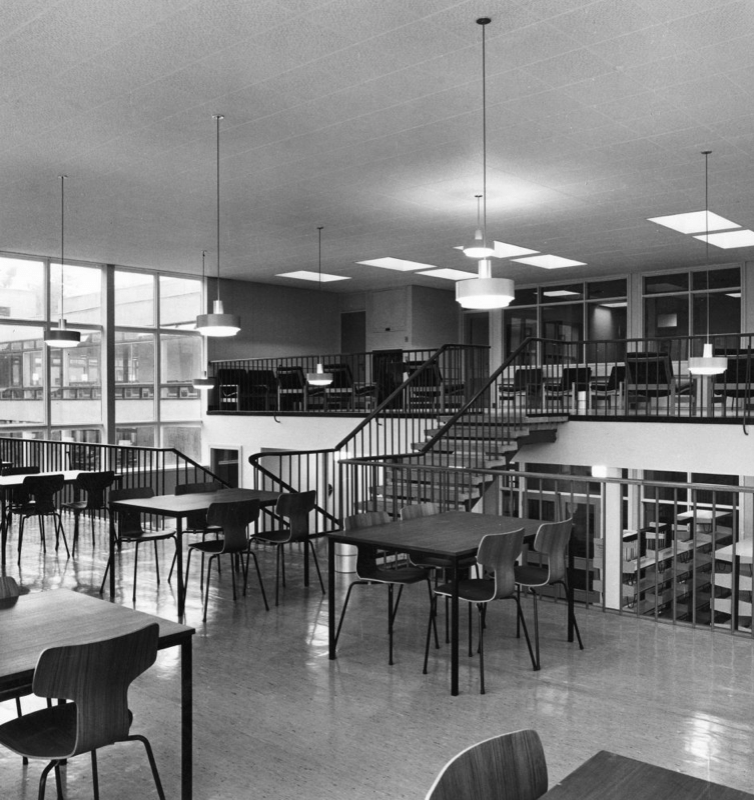

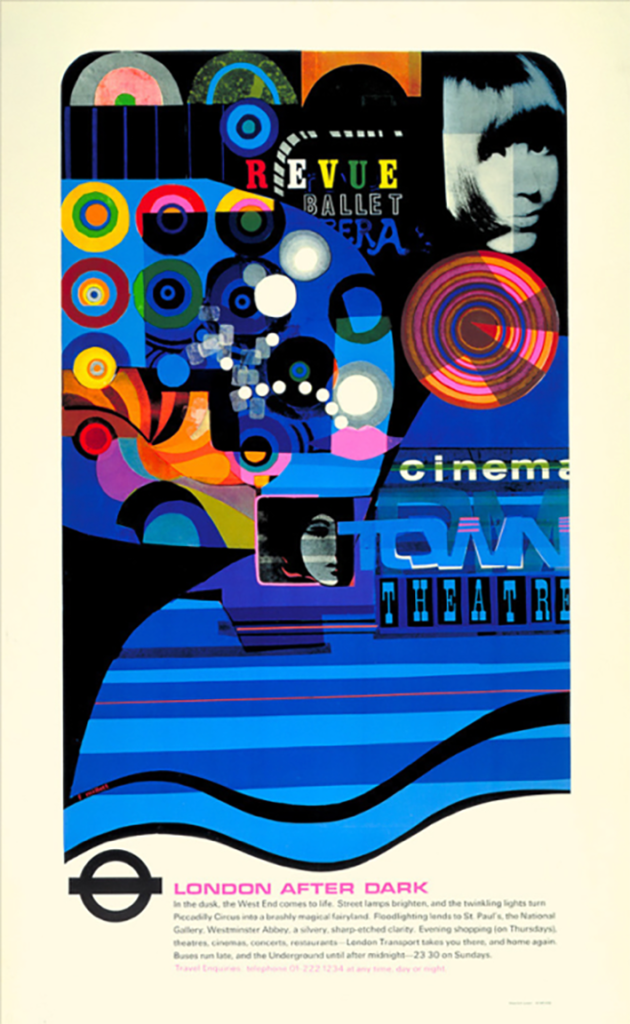

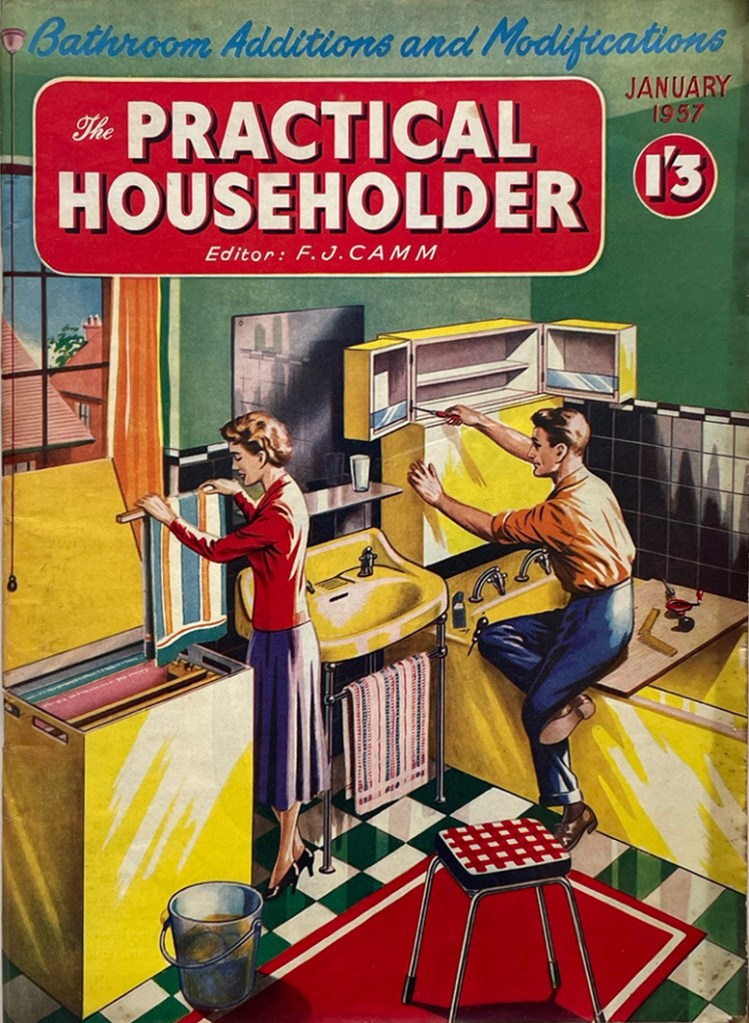

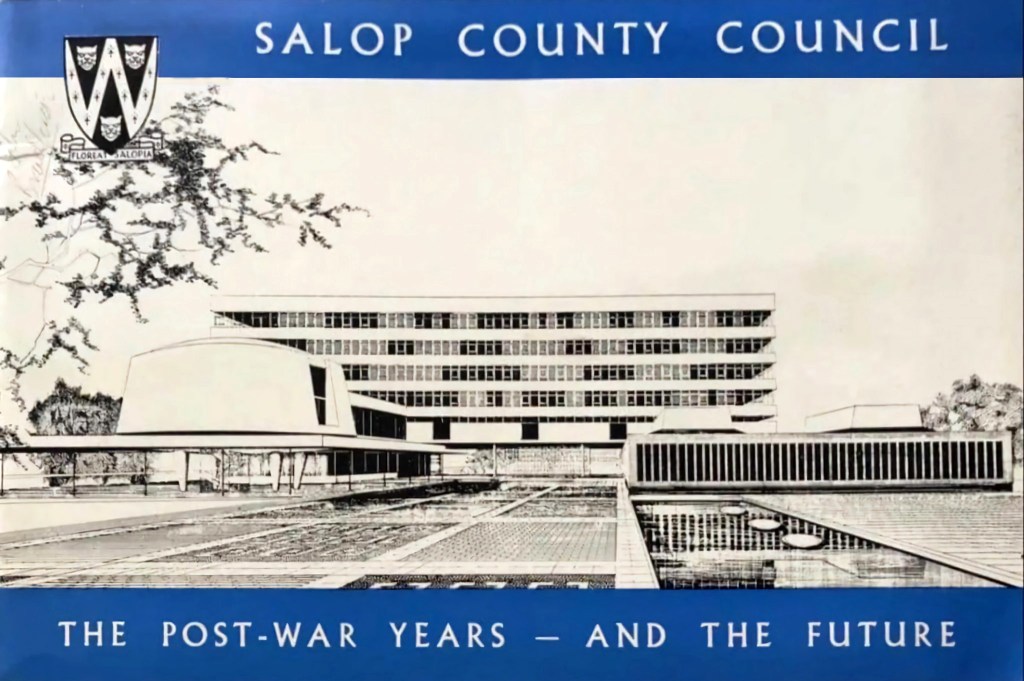

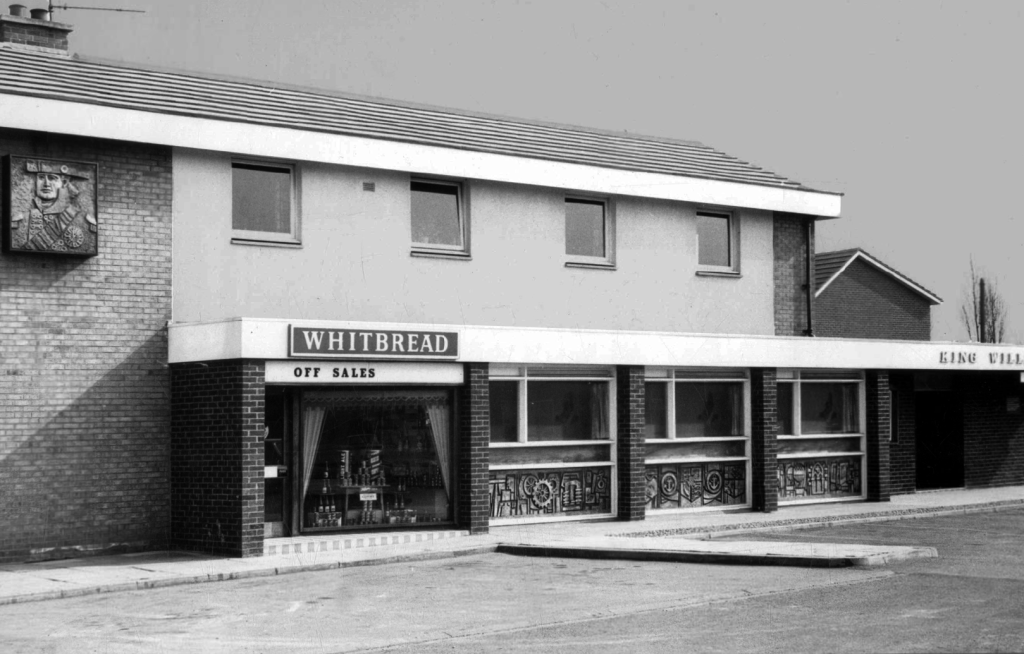

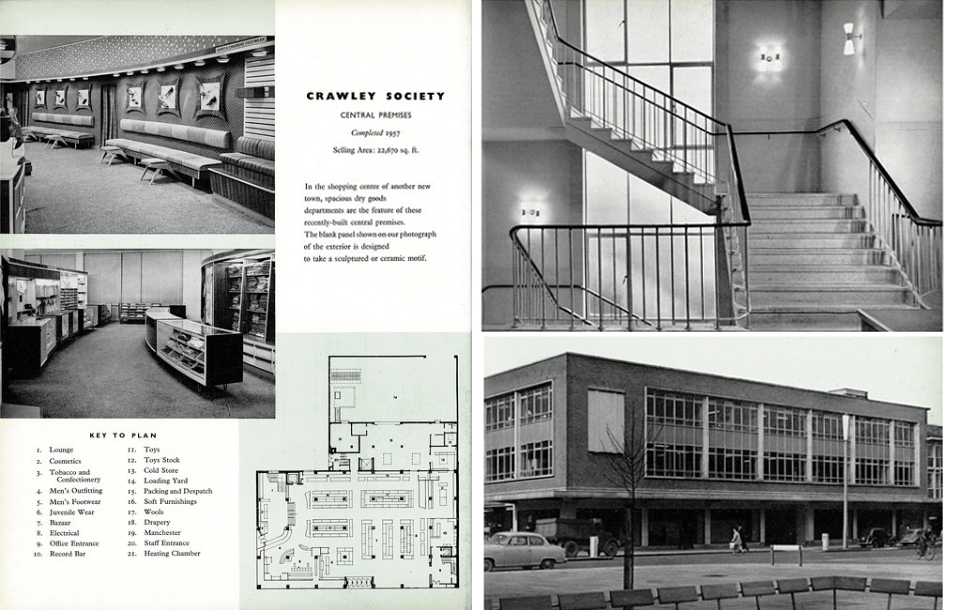

From a very lavish production, printed of course by the CWS’s own Printing Works at Reddish, is a description of the new flagship department store for the Crawley Co-operative Society that was opened in 1959. The elevations and facade are very much of their day, quite ‘Festival of Britain in style, and the store was a prominent feature of the planned New Town’s centre.

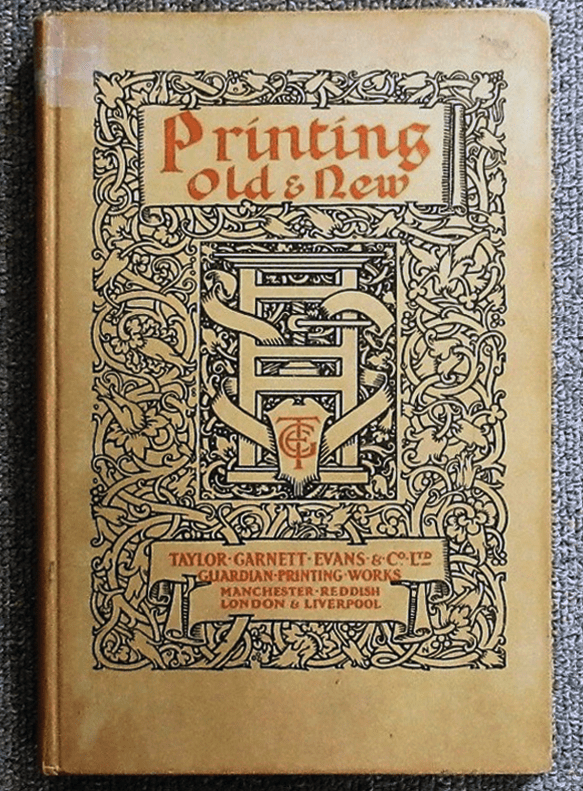

Printed in Reddish.

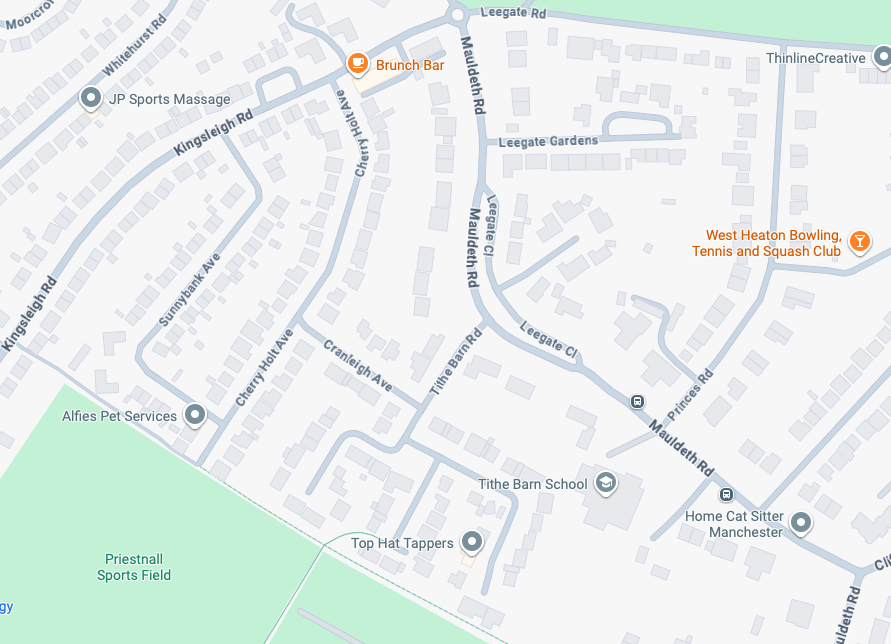

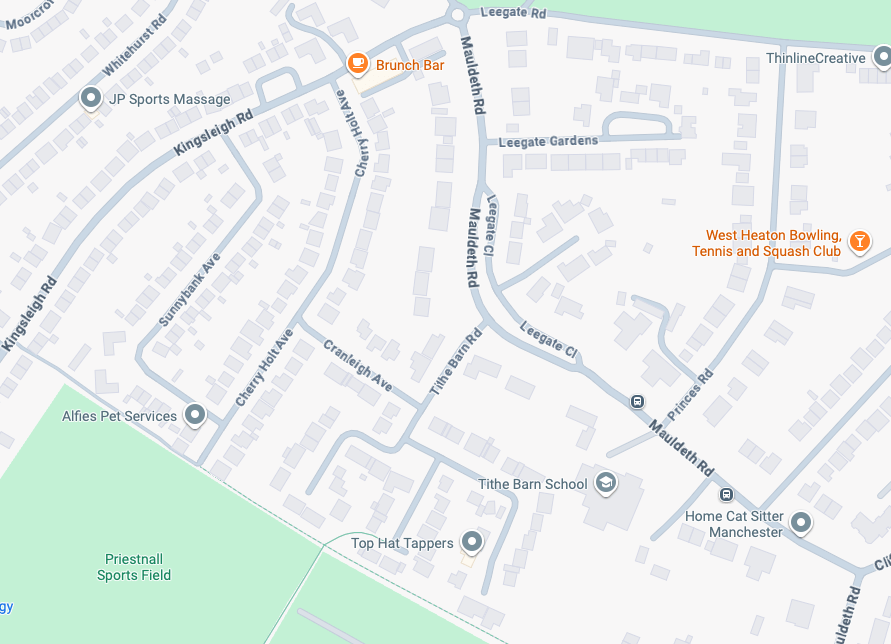

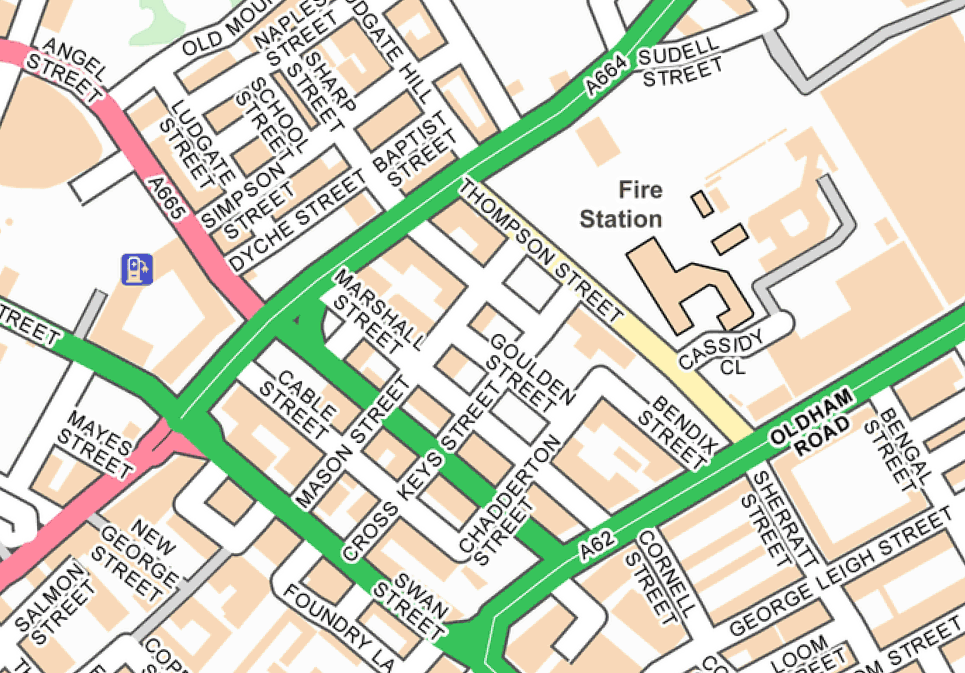

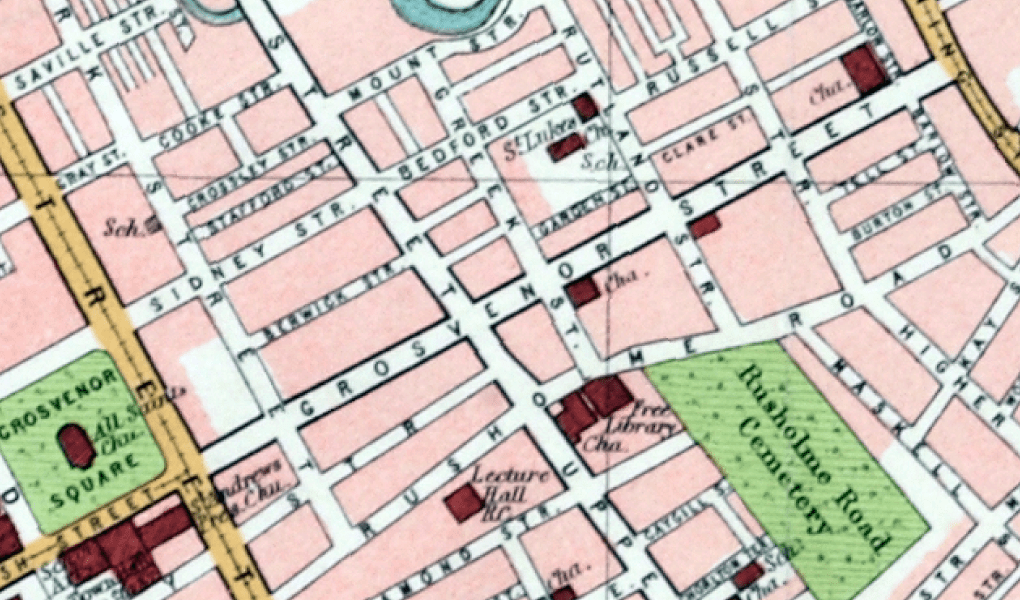

The wide variety of printed material which the CWS required, created a need that could not be met locally by a single source, another large print works was required in Longsight.

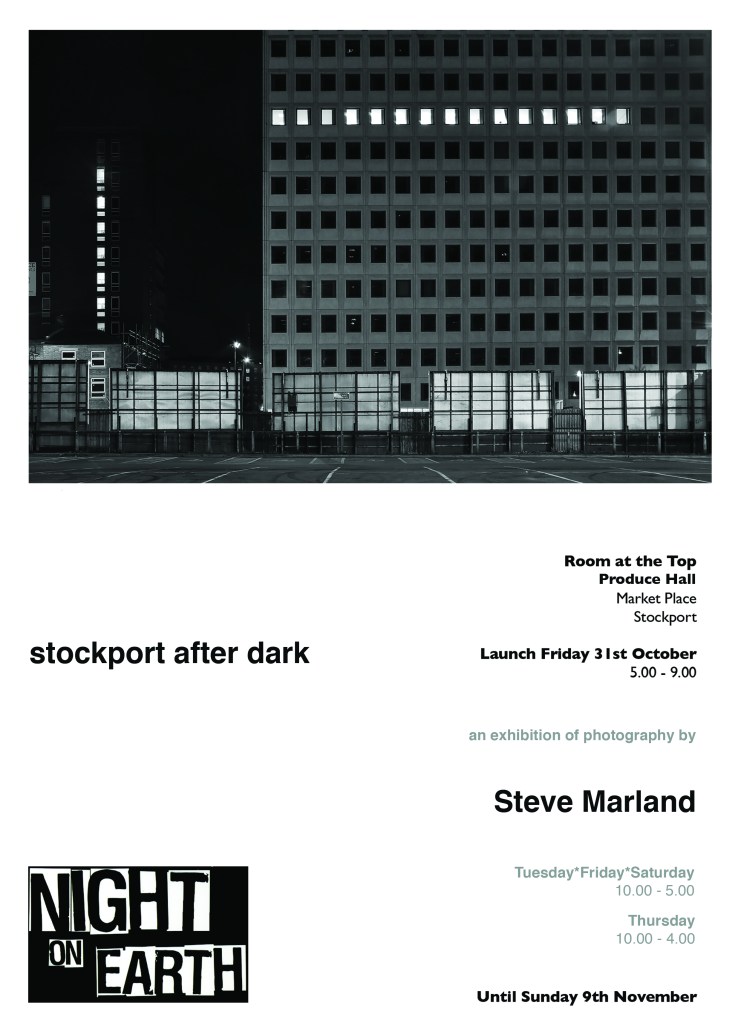

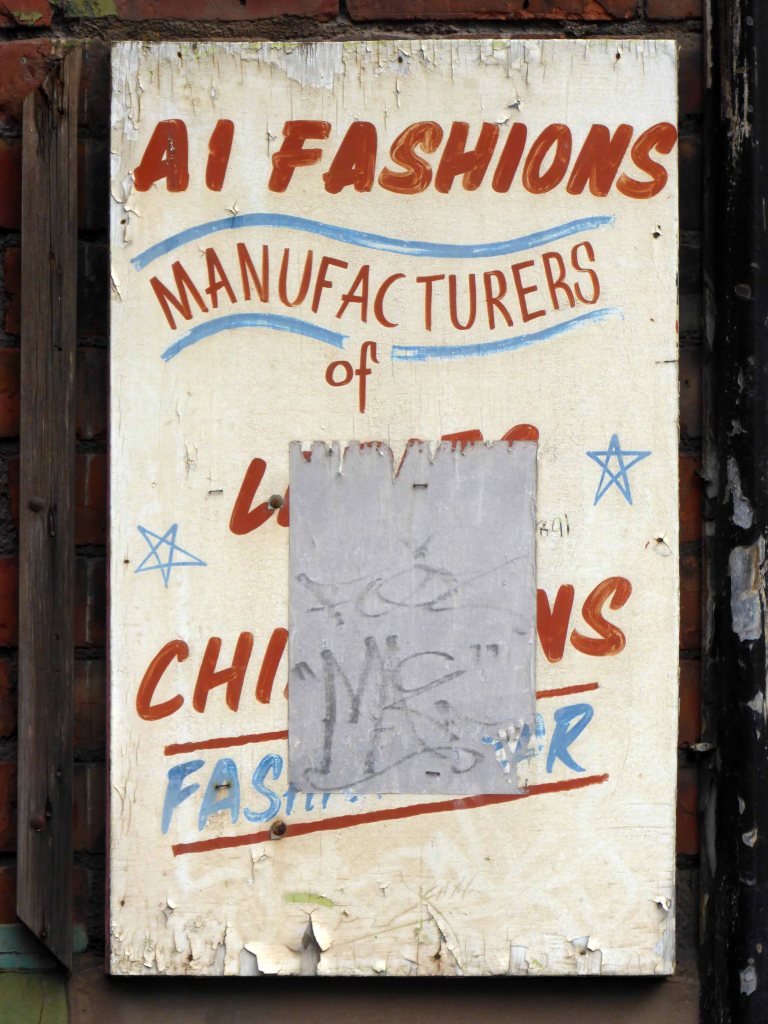

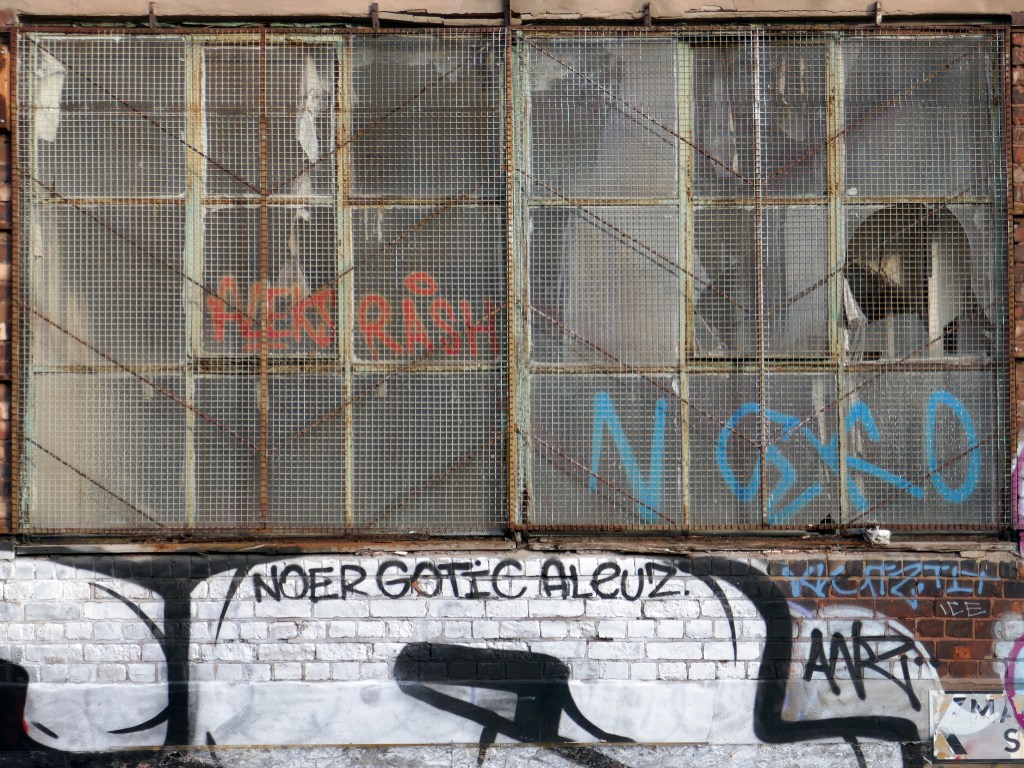

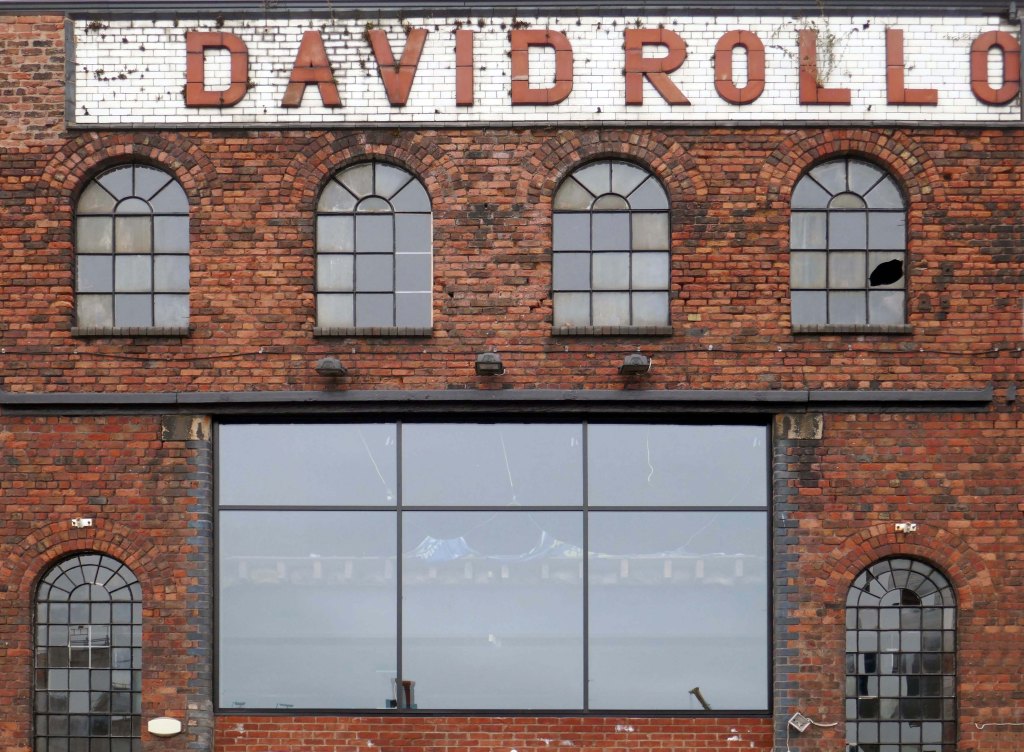

Craven Brothers Works 2008

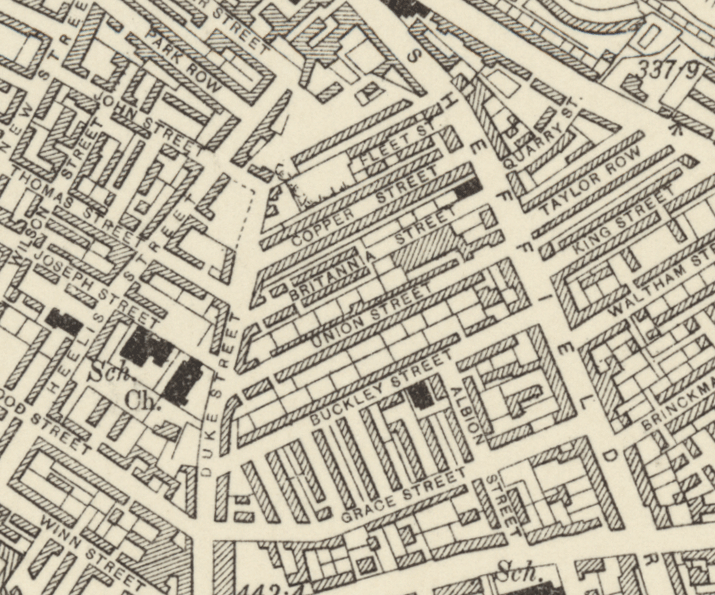

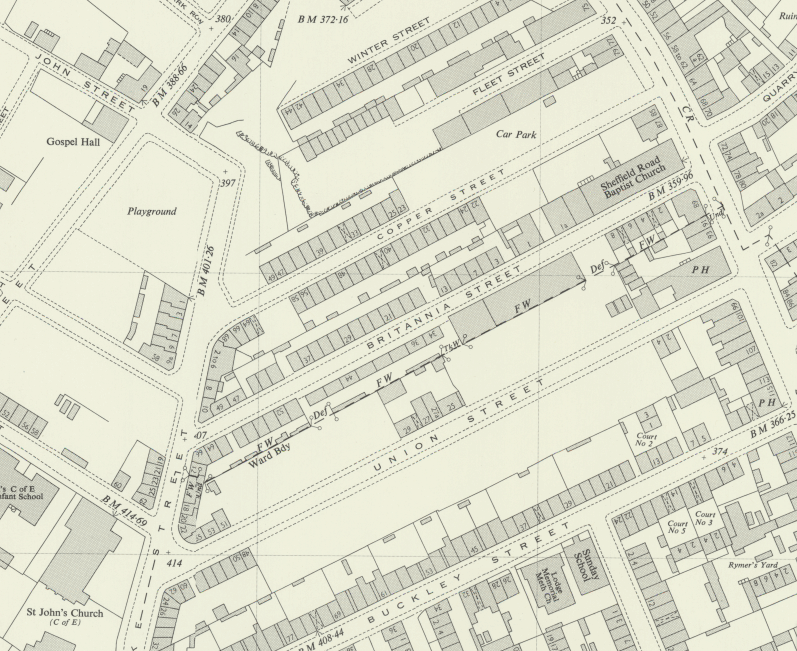

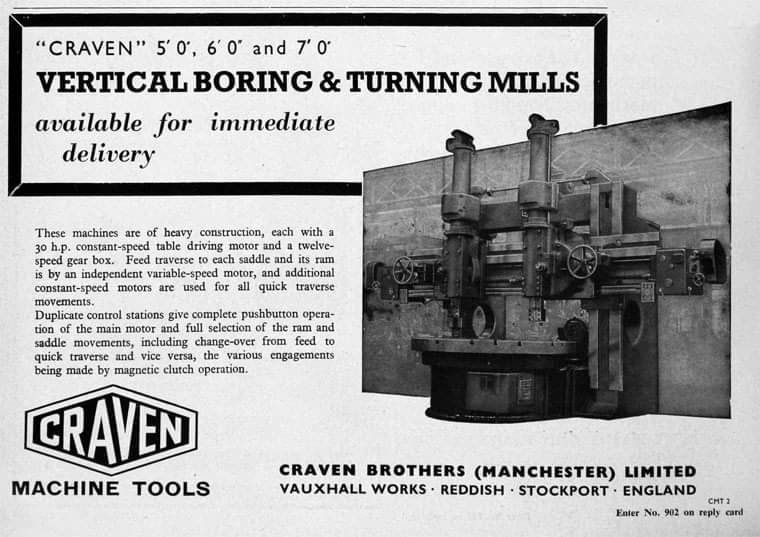

1900 – Further growth prompted the construction of the Vauxhall Works at Reddish, near Stockport. The company kept the works at Osborne Street, Rochdale Road, with about 500 employees, open until 1920. The 1915 O.S. map shows Vauxhall Engineering Works with its south-east corner on Osborne Street, Collyhurst, and bounded on the north by streets of terraced houses and to the south by the L&YR Manchester-Normanton line.

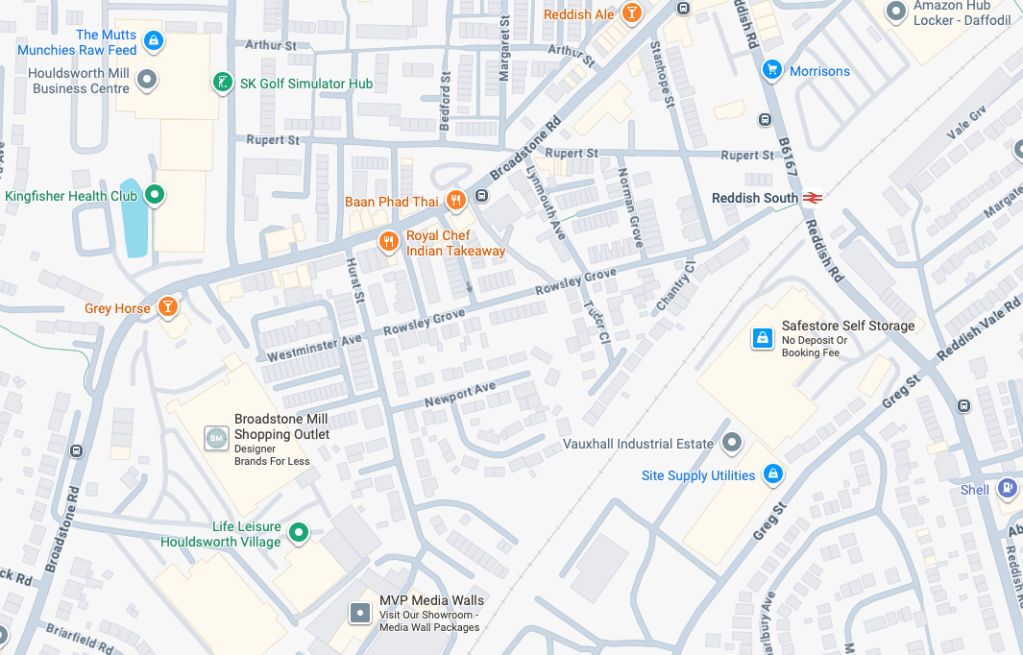

The Developement of Reddish – quite a number of Manchester firms are prospecting the neighbourhood of Reddish, writes a correspondent, while Messrs. Heywood are about to erect electrical engineering works in Sandfold-lane, and Messrs. Rowley and Co, boiler-makers, are fitting works in the neighbourhood. Messrs. Craven Brothers, engineers, of Salford, have purchased 14-acres of land near the Reddish Station, on the estate of Mr. H. P. Greg, on which they intend to erect large engineering works.

The first sod was cut on Thursday afternoon by Mr. William Craven, in the presence of his brother directors in 1900.

Closed in 1970

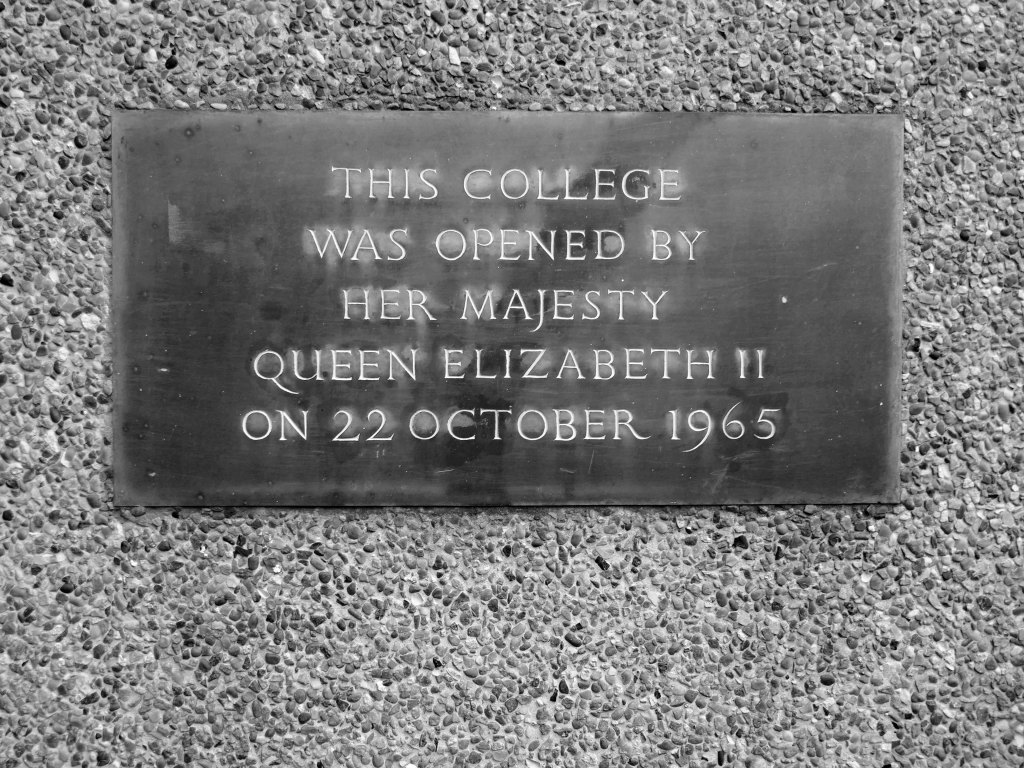

ARC began in 1995 at Greek Street, Stockport under the name of MAPS and moved to the Vauxhall Industrial Estate Craven Works building in early 1997. Arts for Recovery in the Community or ‘Arc’ was then launched in 2005. The Arc Centre in its current form, including gallery servung refreshments and public programme has been running since 2016.

Of course, we are sad to say goodbye to the old Craven Brothers factory and the Reddish community as our base. We are so grateful to the local residents and businesses who have supported us for so long. Please, don’t be strangers! We made the building our own over the years and take with us many, many great memories.

Looking to the future at Wellington Mill, we will have exclusive use of several rooms on the floor accessed via the A6 and Hat Works Museum shop. This will include a large art studio, ceramics studio, offices and storage spaces. We will also share the large cafe, events and retail space with the Hat Works museums team and work together to build a bigger audience for both organisations and hopefully a Stockport town centre creative arts hub.

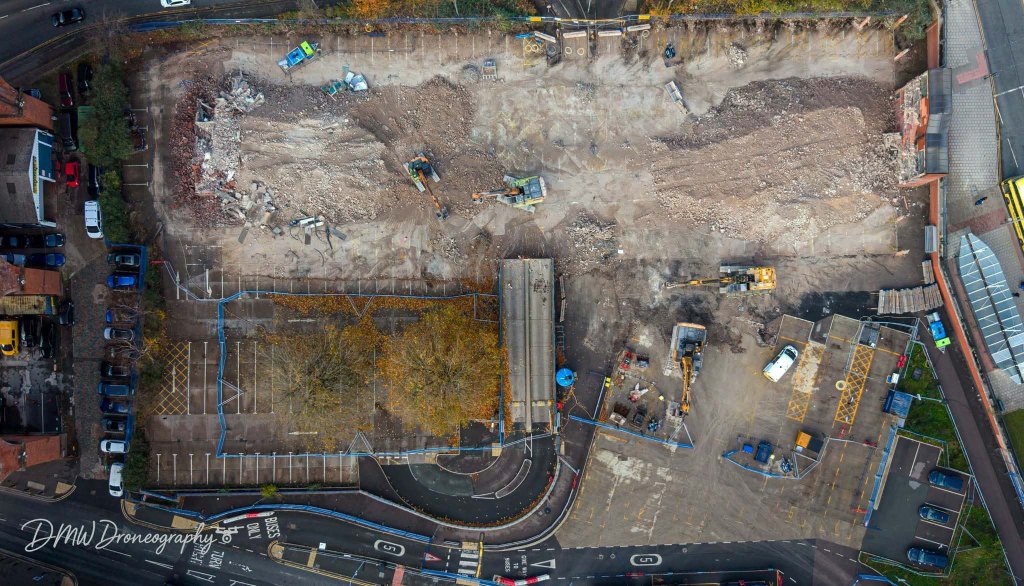

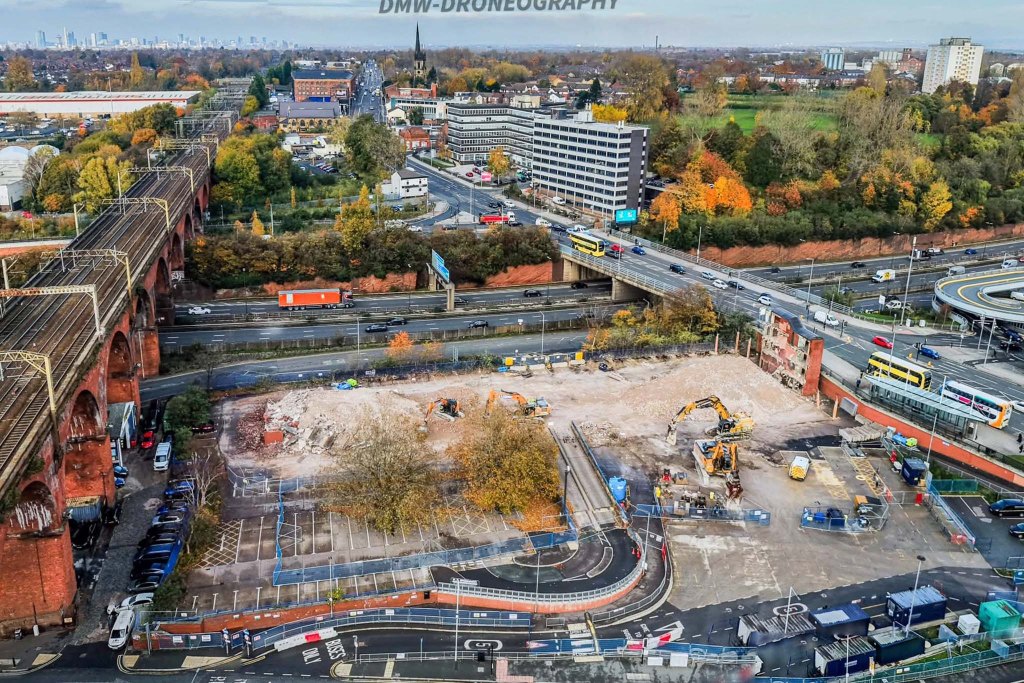

Demolished 2020.

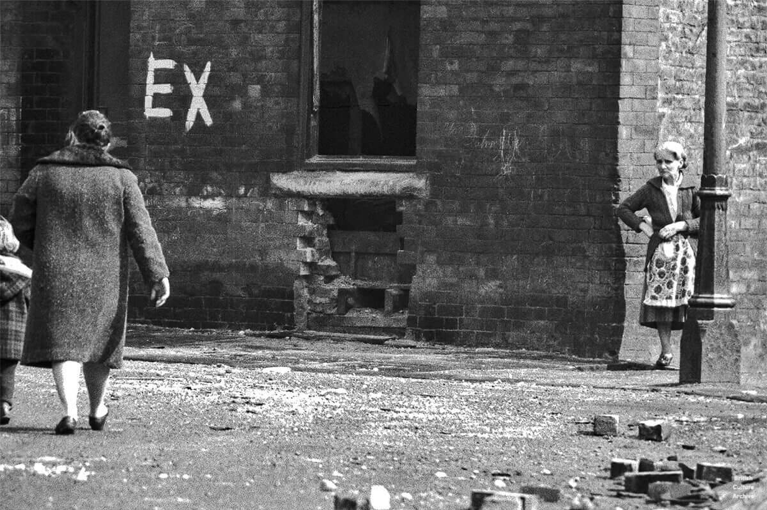

And lo, it came to pass, from the onset of the Industrial Revolution to today, a whole world of work is dismantled. A transport infrastructure is literally filled in, and the former homes of industry demolished.

The CWS is no longer the global behemoth it once was, and print technology has changed beyond recognition.

With it goes a whole series of social relationships and identities bound up in shared occupations.

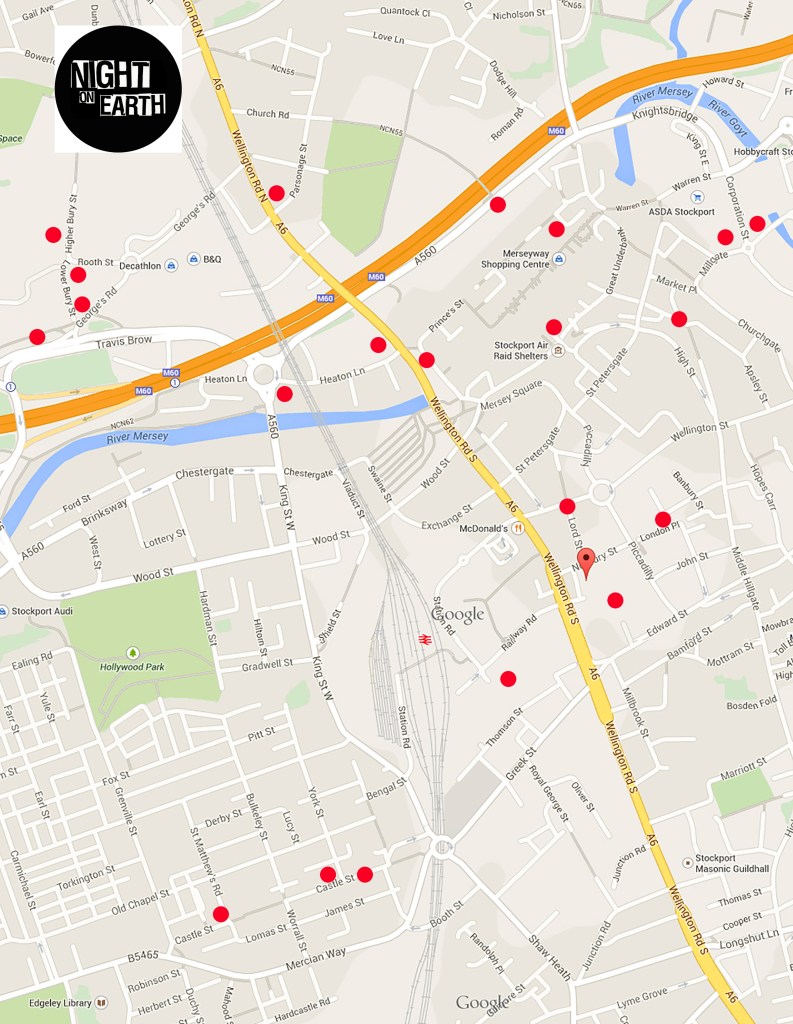

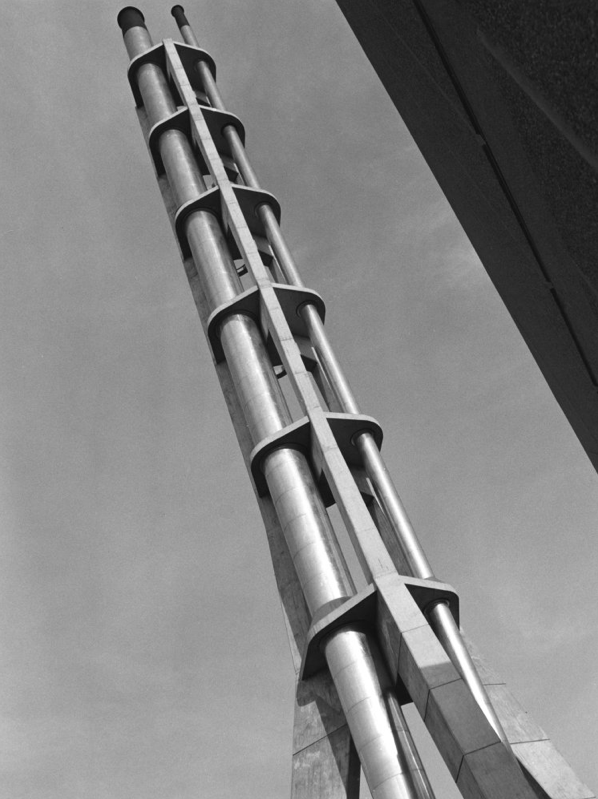

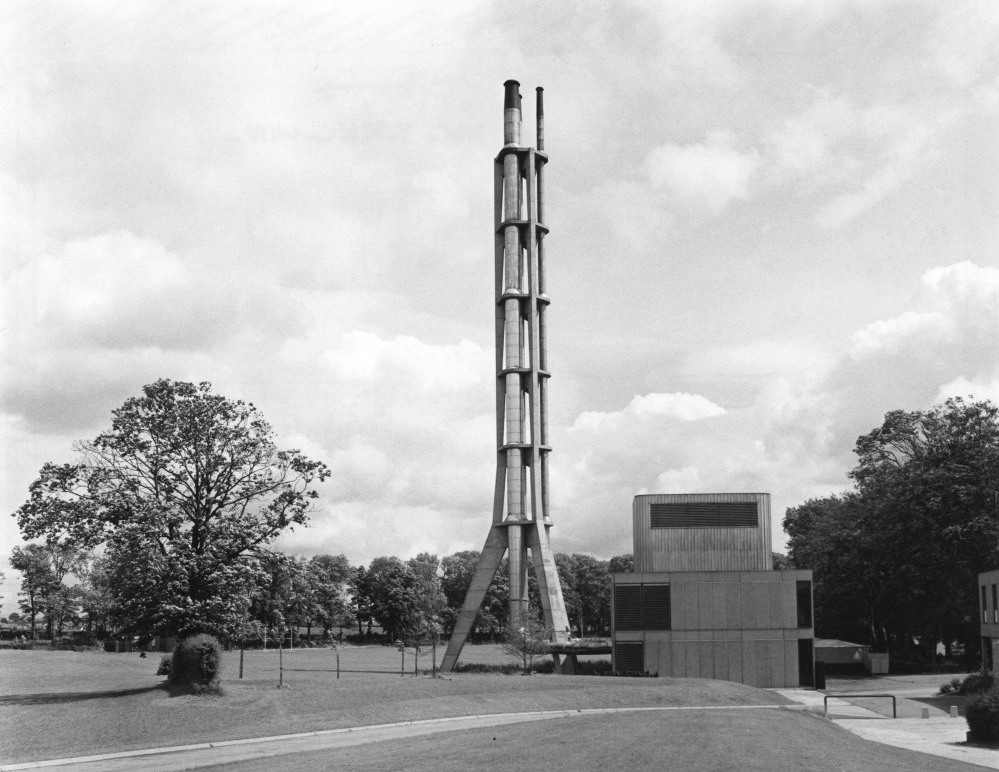

Our excavations at Vauxhall Industrial Estate, undertaken in advance of the redevelopment of the site by RECOM Solutions and Vauxhall Industrial Estate Ltd, revealed a number of features associated with the Craven Brothers’ Works. Two excavation areas were opened, targeted on features shown on historic mapping but no longer surviving: Area 1 in the north, targeting a small chimney and outbuildings adjacent to the machine shops; and Area 2 in the south targeting a chimney and part of the footprint of Building 3. In Area 1, the archaeological remains had been heavily truncated by the installation of chemical vats in the late 20th century after Craven Brothers closed; however, the foundations of the targeted outbuildings and the chimney were uncovered, as well as the remains of a railway track running alongside the machine shops, represented by in situ sleepers.

Archeological Research Services

What do he have now?

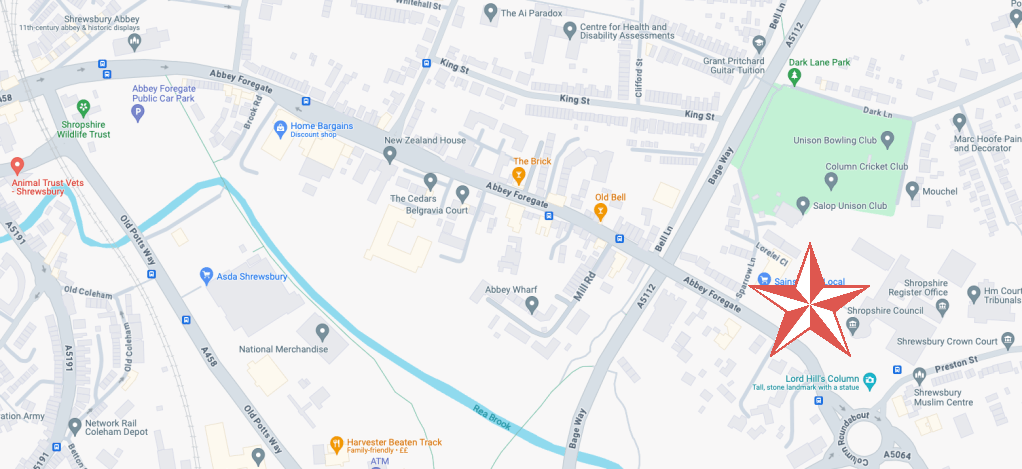

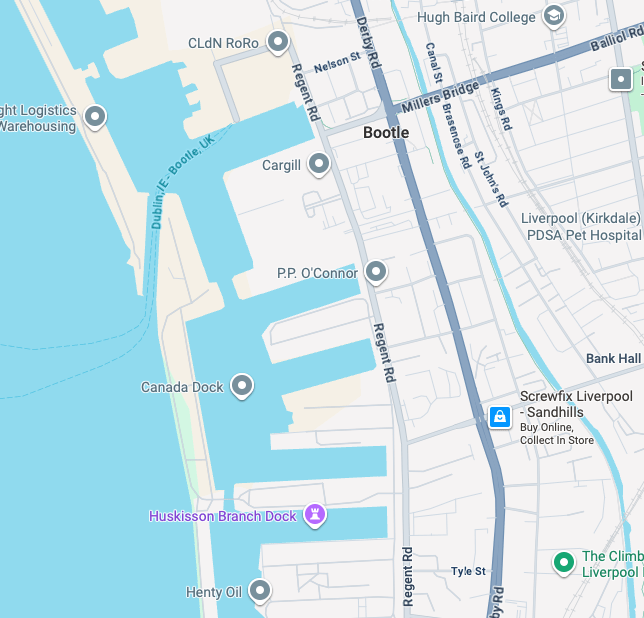

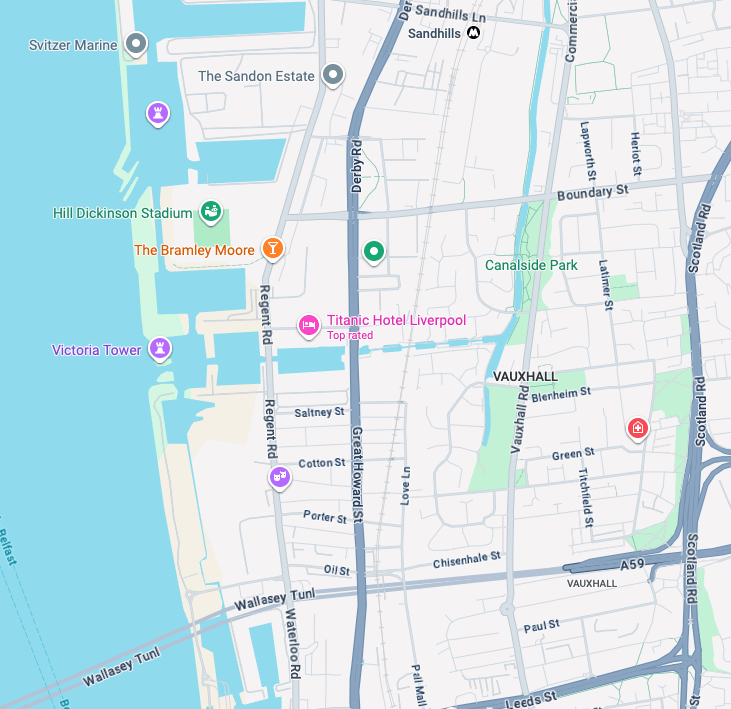

Vauxhall Trading Estate, formerly Vauxhall Industrial Estate, was a collection of dilapidated old industrial buildings, which have been demolished and new modern industrial units provided. RECOM provided project management services to demolish all previous buildings and prepare the site for the main contractor, achieve planning consent, enter a BAPA with Network Rail, tender and appoint the successful main contractor and then provide the Employer’s Agent service throughout the construction phase.

We worked with the design team to produce project specific Employer’s Requirements, ensuring that the client’s brief to provide high quality industrial units was delivered. We ensured the client’s interests were maintained throughout the project, making

objective decisions that aligned with the client’s goals. In order to de-risk the project prior to entering into the main contract, we advised the client on what site investigations, enabling works and surveys needed to be undertaken. As the Employer’s Agent,

we ensured that the conditions of the contract were adhered to, managing claims from the contractor,ensuring that the client’s position was protected.

Project Cost £16.1m

Partners C4 Projects Architects, SATPLAN Planning Consultant, Sixteen/DTRE Letting Agents.

Demolition works and embodied carbon created through construction works, is being offset against the sustainable energy created post occupation including: mix of air-source heat pumps and gas-fired radiant tube heating for heating and cooling, and photovoltaic solar panels installed on rooftops to generate green electricity for occupiers.