Early one morning, six o’clock on Saturday 30th August 2014 to be precise – I set out on my bike from my humble Stockport home, Pendolino’d to Euston, London Bridged to Hastings.

It was my intention to follow the coast to Cleethorpes, so I did.

Five hundred miles or so in seven highly pleasurable days awheel, largely in bright late summer sun. Into each life however, some rain must fall, so it did.

Kent, Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk and Lincolnshire flashed by slowly in lazy succession, to the right the sea – you can’t get lost, though I did. Following Sustrans signs is relatively easy, as long as they actually exist, when I reached Kings Lynn I decided to buy a map.

I set out at eight o’clock on Monday 1st September – I had taken early retirement in March. I would have normally been enrolling new students and teaching photography in a Manchester Further Education College, as I had done for the previous thirty years.

Not today thanks.

With the wind and my former career behind me, I cycled on with an unsurpassable sense of lightness and elation.

This is what I saw.

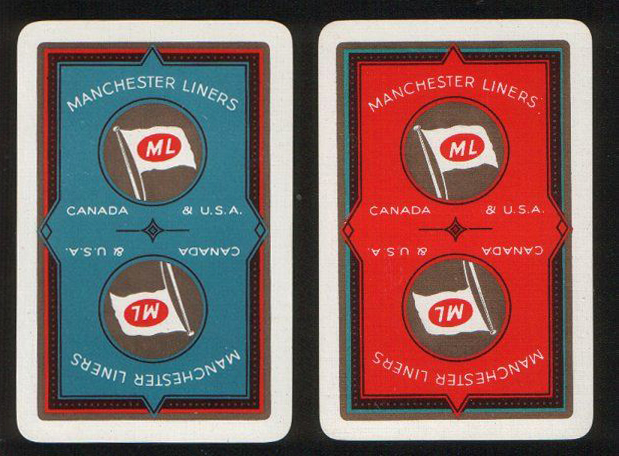

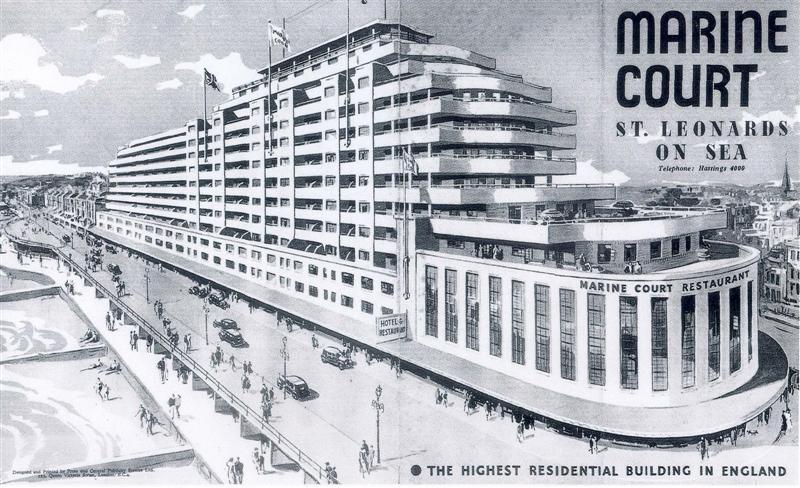

Above and below is Marine Court

The building was designed by architects Kenneth Dalgleish and Roger K Pullen, with overt references to the Cunard White-Star Line Queen Mary, which had entered commercial transatlantic service in 1936. The east end of Marine Court is shaped to imitate the curved, stacked bridge front of the Queen Mary; the eastern restaurant served to imitate the fo’c’sle deck of the ship.

The then Jerwood Gallery looking towards the Old Town’s distinctive fisherman’s sheds.

One grey beach hut bucks the trend.

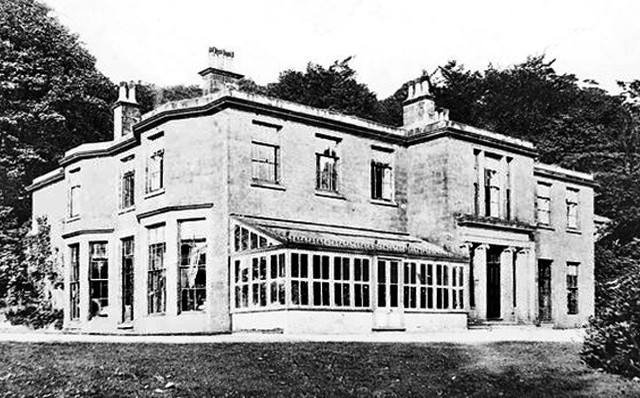

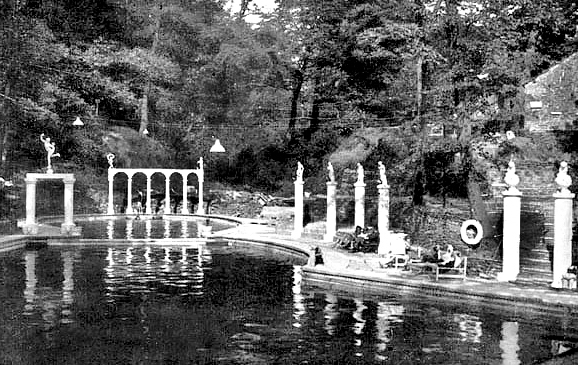

This is all that remains of the St Leonard’s Lido

This is one of many seaside shelters devised by Sidney Little in constructing the concrete promenade – let’s head east.

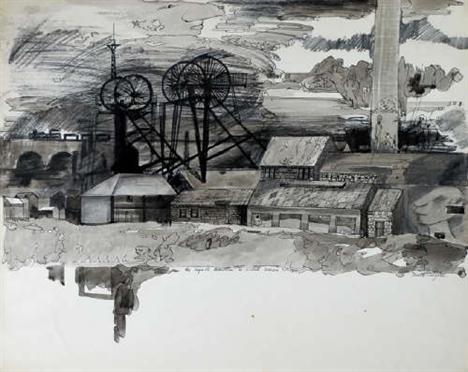

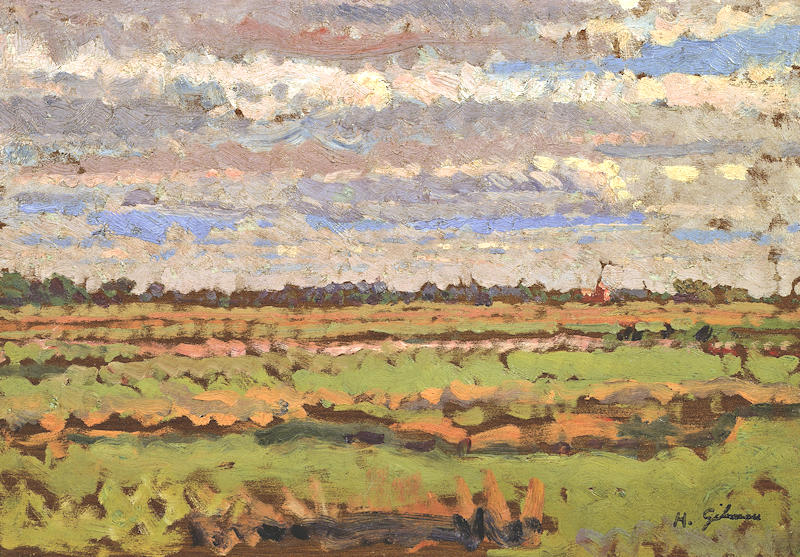

The view across the Romney Marshes from Camber toward Dungeness – which on this occasion I bypassed.

Beloved of many passing painters.

The first Profil aka Stymie Bold Italic encounter – Lyons of Lydd Romney.

Designed by Max and Eugen Lenz and first cast by Haas in 1947.

Heading towards Hythe on the coastal defence path.

Out of Tune Folkestone Seafront, opposite The Leas Lift – is home to AK Dolven’s installation. It features a 16th-century tenor bell from Scraptoft Church in Leicestershire, which had been removed for not being in tune with the others. It is suspended from a steel cable strung between two 20m high steel beams, placed 30m apart.

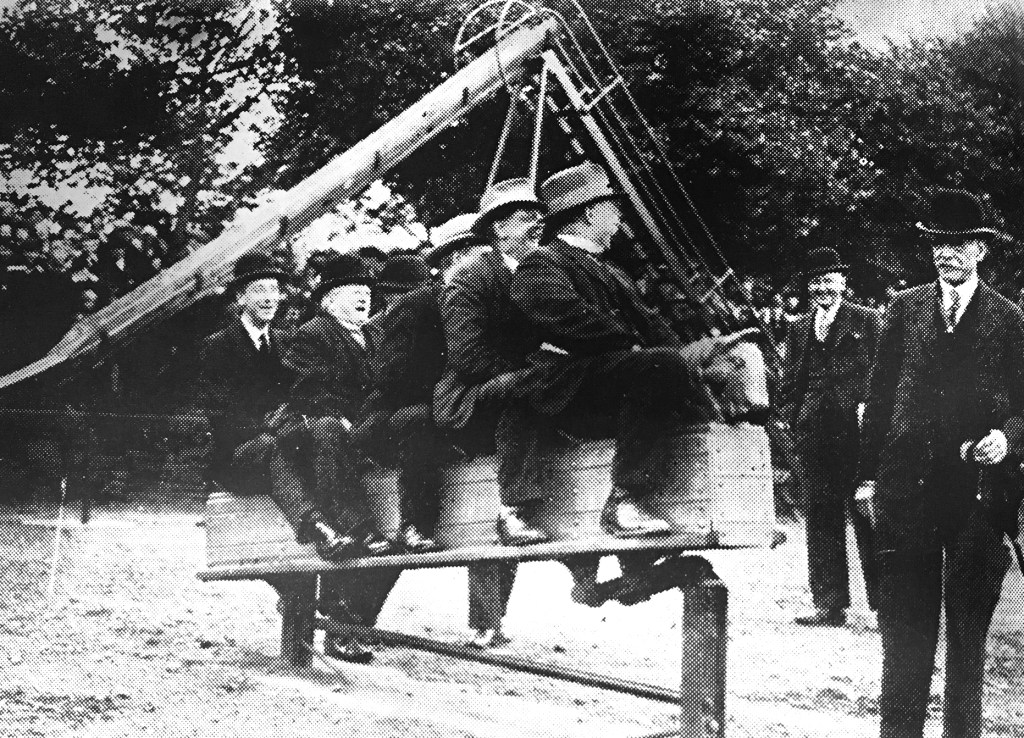

For Folkestone Triennial 2014, Alex Hartley’s response to the title Lookout is inspired by the imposing architecture of the Grand Burstin Hotel, which overlooks the Harbour. For his project Vigil, Hartley will use state of the art climbing technology to make a lookout point suspended from the highest point of the hotel. This climber’s camp will be inhabited for the duration of the Triennial, by the artist and by volunteers, all of whom will keep a log of what they observe.

The current hotel was built in 1984 from the foundations of the Royal Pavilion Hotel, originally built in 1843. Out of the 4,094 reviews currently on TripAdvisor 974 are of the terrible rating which doesn’t inspire much hope.

The most recent review is titled – Dirty Dated Hotel With Clueless Staff.

Kent Live 2018

Gold rush with spades after artist Michael Sailstorfer hides £10,000 of gold on foreshore for town’s Triennial arts festival.

Abbot’s Cliff acoustic mirrors

Before the advent of radar, there was an experimental programme during the 1920s and 30s in which a number of concrete sound reflectors, in a variety of shapes, were built at coastal locations in order to provide early warning of approaching enemy aircraft. A microphone, placed at a focal point, was used to detect the sound waves arriving at and concentrated by the acoustic mirror. These concrete structures were in fixed positions and were spherical, rather than paraboloidal, reflectors. This meant that direction finding could be achieved by altering the position of the microphone rather than moving the mirror.

Eric Ravilious Abbot’s Cliff – 1941

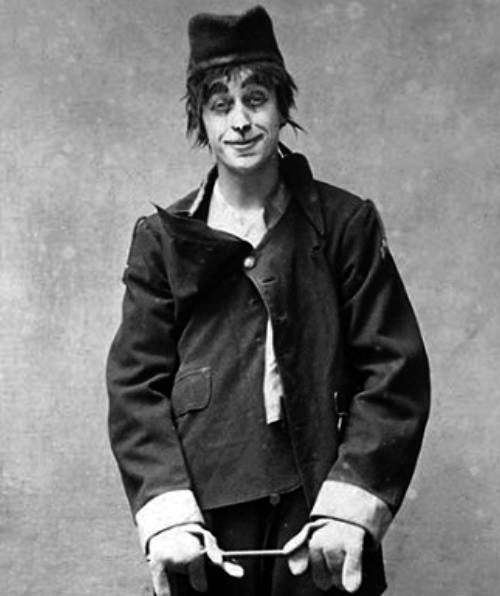

Charles Stewart Rolls was a Welsh motoring and aviation pioneer. With Henry Royce, he co-founded the Rolls-Royce car manufacturing firm. He was the first Briton to be killed in an aeronautical accident with a powered aircraft, when the tail of his Wright Flyer broke off during a flying display in Bournemouth.

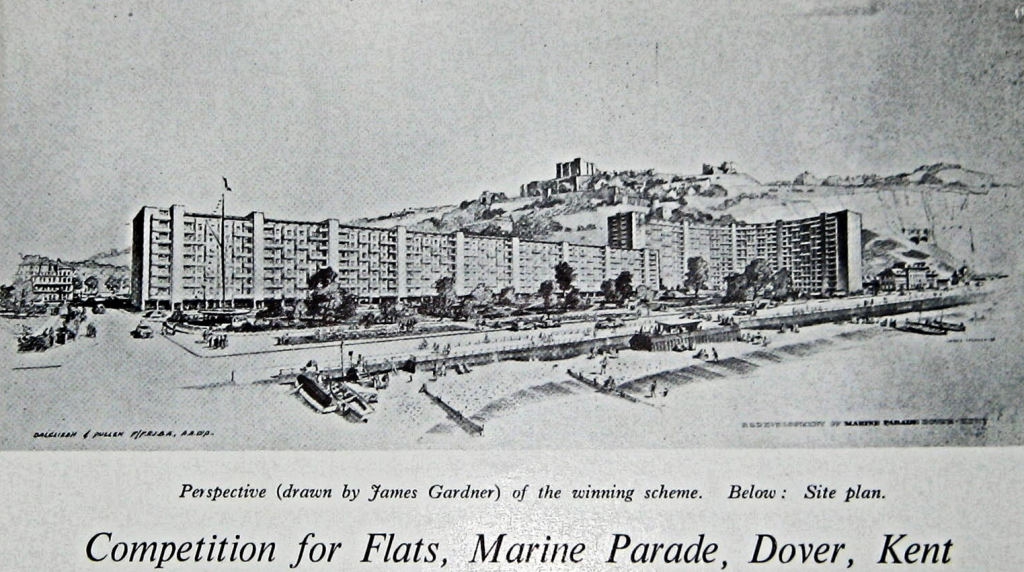

In September 1953 it was announced that Roger K Pullen and Kenneth Dalglish had won and were to receive 100 guineas, for a design for the Gateway Flats.

Local folks would love to re-open The Regent

Behind the Art Deco facade of the Regent was once a grand ironwork and glass Pavilion, built to house regular performances by military bands, which the Edwardian holidaymakers loved. The Lord Warden of the Cinque ports, Lord Beauchamp, officially opened the Pavilion Theatre on Deal’s seafront in 1928.

Deal Pier was designed by Eugenius Birch and opened on 8th November 1864, in 1954 work started on Deal’s third and present-day pier. The new pier took three years to build and was formally opened by the Duke of Edinburgh on 19 November 1957. It was the first seaside pleasure pier of any size to be built since 1910. Designed by Sir W Halcrow and Partners, the 1026ft-long structure comprises steel piles surrounded by concrete casings for the main supports. The pier head originally had three levels but, these days, the lower deck normally remains submerged.

The Kent coastline is home to a vast variety of homes from the crazy clad Prairie Style ranch house to the Debased Deco.

Passing by the prestigious Turner Contemporary

The building was designed by David Chipperfield – It was built on the raised promenade following a flood risk analysis. Construction started in 2008, and was completed for opening in April 2011, at a cost of £17.5 million. The gallery opened on 16 April 2011.

Finally as the sun sets in the west, a pint of something nice in the Harbour Arms.

Night night.